12/31/2016

2016 Comic Reviews and Commentary

Reviews:

Pink

La Quinta Camera

Shazam!: The Monster Society of Evil

Wonder Woman: The True Amazon

Ether #1

The Gods Lie

Star Trek: Boldly Go #1 & Star Trek: Waypoint #1

Ultraman Vol. 4

Beautiful Darkness

Superwoman #1

Deathstroke: Rebirth #1

Snotgirl #1

Wizzywig: Portrait of a Serial Hacker

New Super-Man #1

Superman: American Alien

Hellboy in Hell

DC Universe: Rebirth #1

Ultraman Vol. 3

Wonder Woman: Earth One

Star Wars: Poe Dameron #1 & C-3P0 #1

Black Panther #1

Zodiac Starforce

The Sculptor

If You Steal

The Star Wars

Lulu Anew

Ultraman Vol. 2

Just So Happens

Star Wars: Shattered Empire

Commentary:

More NonSense: Die 2016!

This is our most desperate hour

As if 2016 couldn't get any worse...

More NonSense: And Love Is Love Is Love Is Love

MoreNonSense: The Best of 2016

50th Trek: Redshirts

More NonSense: The Trump Effect

Today I realized I was living in a cartoon

More NonSense: Ms. Marvel will Save You Now

Comic-Con Album Pt 42

Comic-Con Album Pt 41

50th Trek: The Physics of Star Trek

50th Trek: Trekkies (1997)

Comic-Con Album Pt 40

50th Trek: Just a Geek

Comic-Con Album Pt 39

Comic-Con Album Pt 38

R.I.P. Kenny Baker (August 24, 1934 - August 13, 2016)

Comic-Con Album Pt 37

R.I.P. Jack Davis (December 2, 1924 - July 27, 2016)

Video: The Art of Richard Thompson

Comic-Con Album Pt 36

Comic-Con Album Pt 35

Comic-Con Album Pt 34

Comic-Con Album Pt 33

Comic-Con Album Pt 32

More NonSense: Hail Hydra!

Comic-Con Album Pt 31

Comic-Con Album Pt 30

Comic-Con Album Pt 29

R.I.P. Muhammad Ali (January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016)

DC Universe: Rebirth #1

More NonSense: Dawn of the Civil War

More Nonsense Jon Snow Lives!

More NonSense: Purple Rain

More NonSense: Die 2016!

The Beat Staff list their best comics of 2016, Also the best films, and games.

Vox lists their best comics of 2016.

ComicsAlliance lists their best comics of 2016.

ComicsAlliance remembers the people in comics who died in 2016.

Sean T. Collins on the Fascism of The Walking Dead.

Remember that infamous American Sailor Moon adaptation? Rich Johnston does.

Tom Spurgeon and Michael Dean present an excerpt (Pt 1, 2) of We Told You So: Comics as Art. That Gary Groth, what a scamp.

Sean T. Collins lists The 50 Greatest Star Wars Moments. Did you know that Star Wars continuity is a complete mess like any other longstanding franchise? And its politics are pretty extreme, to say the least.

Rogue One introduced the Guardians of the Whills, recalling one of the more obscure pieces of Lucas lore. But even more interesting is that these characters were played by Donnie Yen and Jiang Wen. Apparently, Chirrut Imwe and Baze Malbus are the new Finn/Poe? Makes sense to me.

But the most unfortunate news of all was the death of Carrie Fisher (October 21, 1956 – December 27, 2016), followed a day later by her mother Debbie Reynolds (April 1, 1932 – December 28, 2016), which I covered here.

Mark Peters dredges up the old debate of Jack Kirby's possible influence on the Star Wars franchise.

Beethoven!

Elle Collins on the repercussions faced by creators working on corporate properties when they express dissenting opinions.

R.I.P. George Michael (25 June 1963 – 25 December 2016). This year has been kicking our ass.

Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner blame Poe's Law for making 2016 such a terrible year.

Labels:

animation,

anime,

cartoon,

Charles Schulz,

Commentary,

creator rights,

fantasy,

film,

gender roles,

industry,

Jack Kirby,

Ludwig van Beethoven,

music,

Peanuts,

politics,

Star Wars,

television,

The Walking Dead

12/28/2016

This is our most desperate hour

Star Wars (1977)

Star Wars (1977)

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Postcards from the Edge

When Harry Met Sally (1989)

The Force Awakens (2015)

The Force Awakens (2015)

The Princess Diarist

R.I.P. Carrie Fisher (October 21, 1956 – December 27, 2016).

Fisher is survived by her mother Debbie Reynolds, her brother, Todd Fisher, her daughter, Billie Lourd, and Gary the dog.

Tributes from: Fellow celebrities, more celebrities, George R.R. Martin, Peter Travers, Sean T. Collins, Bully, Glen Weldon, Mike Sterling, ComicsAlliance, Edie Nugent, Kevin Fitzpatrick, Katharine Trendacosta, Sam Machkovech, Lindsay Kimble, Sam Adams, Harry Dreyfus, Melanie Mcfarland, Kevin Carlin, Heather Schwedel, David Edelstein, Melissa Locker, Mary Elizabeth Williams,

Update: R.I.P. Debbie Reynolds (April 1, 1932 – December 28, 2016), the star of the 1952 hit "Singin' in the Rain."

2016, you are most cruel.

|

| Vader's Little Princess |

12/25/2016

Pink

By Kyoko Okazaki

Translation: Vertical Inc.

For my generation, the 1980s were a more innocent time. Remembered for the end of the Cold War and the rise of unbridled consumerism, the decade was marked by Japan’s emergence from its postwar funk to become the world’s 2nd greatest economic powerhouse, after the United States. So impressive was Japan’s rapid ascension that there was even talk of a changing of the status quo in the near future. It sounds silly in retrospect, but Japan looked almost unstoppable. Most Western fans will remember Akira, the manga and its anime adaptation, as a creation of this heady period. Its cyberpunk vision of a dystopian future would prove to be very influential to a generation of growing fanboys. But youthful rebellion can take on many forms, and mangaka Kyoko Okazaki portrayed a modern society where women had unprecedented freedom from the constraints of traditional expectations. Initially published in 1989, Pink is not as shocking today. But contemporary readers must have found its female protagonists’ relative economic security and flaunting of sexual mores to be undeniably cool.

And Pink doesn’t need violent bosozoku gangs or freedom fighters taking down the government to make a similarly brash statement. All it takes is one bored office lady (Japan’s favorite dead end job for single women expected by society to get married) moonlighting as a call girl. Twenty something Yumi doesn’t really need the dough to survive. Her apparently wealthy (but unseen) father pays the rent for her apartment. But this hardly meets the lifestyle she’s accustomed to. So she earns considerably more capital by fulfilling the carnal desires of her clientele of mostly older men.

Needless to say, there’s a fair amount of sexual activity illustrated in the manga. It’s all pretty tame given what can be now seen on HBO. There’s abundant and artfully drawn nudity, though male genitalia are only implied. But it’s definitely calculated to tow the fine line between the provocative and pornographic. In fact, Yumi’s escapades often take a more surreal turn. One client robs her blind but leaves her a magical seed. Another verbally abuses her, but succeeds in making her come “for real.” She later catches him being interviewed on a television talk show where he speaks for the humane treatment of wild animals. Yumi then recalls that he carried a “fat wallet made from crocodile leather,” prompting a giggling fit. At least she got paid handsomely to satisfy both their animal cravings. In the manga’s afterward, Okazaki quotes Jean-Luc Godard’s maxim “all work is prostitution” then claims “Love isn’t that tepid and lukewarm thing people like to talk about… It’s a tough, severe, scary, and cruel monster. So is capitalism.”

This impudent and unsentimental attitude towards sex, romance, and life exhibited by Okazaki isn’t exactly the subversive aesthetic of alternative American comics. The pose assumed is mostly one of lighthearted mockery. She’s celebrating the system as much as she’s critiquing it. In Japan, her work was considered an important step away from the conventions of shojo manga, earning the label “Gyaru,” translated into English as “Gal.” Gals were a tougher, more modern breed who weren’t afraid to pursue love and happiness. Suddenly, there was a market for a more grown-up female audience. And Okazaki’s art certainly reflects a more adult sensibility. It lacks the surface polish and cute character designs often found in shonen and shojo manga. But the looseness of line and dearth of obsessive detail reveals a assuredness in her page compositions and expressiveness in her characters. There’s a manic energy in Okazaki’s art that feels both appealing and unsettling.

Yumi’s casually irreverent approach to materialism is contrasted with the haughty behavior of her stepmother’s, a representative of how women are traditionally supposed to accumulate wealth and social status - using their beauty and erotic charms to marry into it. This golddigger naturally hates Yumi for her modern ways and envies her youth while she tries in vain to preserve her own with visits to the plastic surgeon and carrying on affairs with younger men. If this fails to remind anyone of Snow White, Okazaki pretty much hits the reader over the head repeatedly with this symbolism. Her machinations are what drive the plot forward.

The story’s would-be Prince Charming is college student and aspiring novelist Haru. But he’s actually more a pawn caught between these two formidable women. Haru sleeps around in the hopes of sparking the inspiration to begin his novel. But while Yumi teases Haru for his uncertainty, her even more ferocious kid sister Keiko admonishes him to drop his literary pretentions, get off his ass, and start writing a story that even a kid can understand. Lo and behold, Haru later proves to be just as opportunistic as his female counterparts.

But the most bizarre character in Pink is Yumi’s pet crocodile, whom she’s cared for and miraculously managed to keep alive in her cramped apartment. Obtaining the resources to feed Croc, as Yumi calls him, is her excuse for her call girl career. Despite being drawn as an almost cuddly, impassive, and bespectacled toy, Croc is a clumsy metaphor for the cruel monster of love and capitalism Okazaki subscribes to. But he’s also a sign of the fragile freedom and relative comfort Yumi has obtained on her very own terms. Therein lies the rub. What happens when the monster you worked so hard to satiate turns on you? Or even worse, simply abandons you? That’s a question would become prescient to Okazaki when her career was cut short by an auto accident, and to the Japanese economy within a few years.

Translation: Vertical Inc.

For my generation, the 1980s were a more innocent time. Remembered for the end of the Cold War and the rise of unbridled consumerism, the decade was marked by Japan’s emergence from its postwar funk to become the world’s 2nd greatest economic powerhouse, after the United States. So impressive was Japan’s rapid ascension that there was even talk of a changing of the status quo in the near future. It sounds silly in retrospect, but Japan looked almost unstoppable. Most Western fans will remember Akira, the manga and its anime adaptation, as a creation of this heady period. Its cyberpunk vision of a dystopian future would prove to be very influential to a generation of growing fanboys. But youthful rebellion can take on many forms, and mangaka Kyoko Okazaki portrayed a modern society where women had unprecedented freedom from the constraints of traditional expectations. Initially published in 1989, Pink is not as shocking today. But contemporary readers must have found its female protagonists’ relative economic security and flaunting of sexual mores to be undeniably cool.

And Pink doesn’t need violent bosozoku gangs or freedom fighters taking down the government to make a similarly brash statement. All it takes is one bored office lady (Japan’s favorite dead end job for single women expected by society to get married) moonlighting as a call girl. Twenty something Yumi doesn’t really need the dough to survive. Her apparently wealthy (but unseen) father pays the rent for her apartment. But this hardly meets the lifestyle she’s accustomed to. So she earns considerably more capital by fulfilling the carnal desires of her clientele of mostly older men.

Needless to say, there’s a fair amount of sexual activity illustrated in the manga. It’s all pretty tame given what can be now seen on HBO. There’s abundant and artfully drawn nudity, though male genitalia are only implied. But it’s definitely calculated to tow the fine line between the provocative and pornographic. In fact, Yumi’s escapades often take a more surreal turn. One client robs her blind but leaves her a magical seed. Another verbally abuses her, but succeeds in making her come “for real.” She later catches him being interviewed on a television talk show where he speaks for the humane treatment of wild animals. Yumi then recalls that he carried a “fat wallet made from crocodile leather,” prompting a giggling fit. At least she got paid handsomely to satisfy both their animal cravings. In the manga’s afterward, Okazaki quotes Jean-Luc Godard’s maxim “all work is prostitution” then claims “Love isn’t that tepid and lukewarm thing people like to talk about… It’s a tough, severe, scary, and cruel monster. So is capitalism.”

This impudent and unsentimental attitude towards sex, romance, and life exhibited by Okazaki isn’t exactly the subversive aesthetic of alternative American comics. The pose assumed is mostly one of lighthearted mockery. She’s celebrating the system as much as she’s critiquing it. In Japan, her work was considered an important step away from the conventions of shojo manga, earning the label “Gyaru,” translated into English as “Gal.” Gals were a tougher, more modern breed who weren’t afraid to pursue love and happiness. Suddenly, there was a market for a more grown-up female audience. And Okazaki’s art certainly reflects a more adult sensibility. It lacks the surface polish and cute character designs often found in shonen and shojo manga. But the looseness of line and dearth of obsessive detail reveals a assuredness in her page compositions and expressiveness in her characters. There’s a manic energy in Okazaki’s art that feels both appealing and unsettling.

Yumi’s casually irreverent approach to materialism is contrasted with the haughty behavior of her stepmother’s, a representative of how women are traditionally supposed to accumulate wealth and social status - using their beauty and erotic charms to marry into it. This golddigger naturally hates Yumi for her modern ways and envies her youth while she tries in vain to preserve her own with visits to the plastic surgeon and carrying on affairs with younger men. If this fails to remind anyone of Snow White, Okazaki pretty much hits the reader over the head repeatedly with this symbolism. Her machinations are what drive the plot forward.

The story’s would-be Prince Charming is college student and aspiring novelist Haru. But he’s actually more a pawn caught between these two formidable women. Haru sleeps around in the hopes of sparking the inspiration to begin his novel. But while Yumi teases Haru for his uncertainty, her even more ferocious kid sister Keiko admonishes him to drop his literary pretentions, get off his ass, and start writing a story that even a kid can understand. Lo and behold, Haru later proves to be just as opportunistic as his female counterparts.

But the most bizarre character in Pink is Yumi’s pet crocodile, whom she’s cared for and miraculously managed to keep alive in her cramped apartment. Obtaining the resources to feed Croc, as Yumi calls him, is her excuse for her call girl career. Despite being drawn as an almost cuddly, impassive, and bespectacled toy, Croc is a clumsy metaphor for the cruel monster of love and capitalism Okazaki subscribes to. But he’s also a sign of the fragile freedom and relative comfort Yumi has obtained on her very own terms. Therein lies the rub. What happens when the monster you worked so hard to satiate turns on you? Or even worse, simply abandons you? That’s a question would become prescient to Okazaki when her career was cut short by an auto accident, and to the Japanese economy within a few years.

12/22/2016

12/17/2016

La Quinta Camera

By Natsume Ono

Translation: Joe Yamazaki

Touch-up Art/Lettering: Gia Cam Luc

Design: Fawn Lau

La Quinta Camera was a webcomic series that established Natsume Ono as a mangaka in Japan, but was translated by Viz after her later work Ristorante Paradiso. Nonetheless, one can see a number of commonalities between the two works. Ono displays an early fascination with the Western cultural milieu, particularly Italy. And just as in Ristorante Paradiso, the manga has a thing for adult males of a certain age. Even in her first story, Ono handles the lives of her characters with a deft and light touch, devoid of any cheap melodrama.

The manga does contain a few surprises. Considering Ono’s more mature minimalist style, La Quinta Camera’s art is practically primitive by comparison. Ono’s figures are blockier and more squat, almost reminiscent of early Cubism. Her lines are more uniform, as if she only used technical pens which produced a certain line thickness. This results in characters who are more archetypal in appearance. They’re recognizable primarily through larger features like their hairstyles, or preferred items of clothing.

Ono also uses a much simpler setup to make her story work. In the first chapter, a young woman from Denmark arrives at an unnamed Italian city and immediately suffers a series of mishaps. We learn that she’s here to learn the language. But after losing her personal belongings, getting lost, interacting with a few of the locals, and finally managing to find the language school, she’s directed to an apartment building for her room and board. To her surprise, she discovers that her hosts happen to be the very locals she met earlier on the street. If this were a more conventional story, the rest of the manga would be about the fish-out-of-water misadventures of the woman and her 4 eccentric roommates.

But this isn’t the case at all. In the next chapter, the woman has already moved out of the apartment and an artist has moved into the room. We learn that the owner has arranged with the school to rent the apartment’s 5th room to the school’s foreign students, who usually stay for a short period. Each chapter introduces a different student, and their outside perspective allows us to learn a little more about the 4 permanent residents in the apartment.

While they might not be the center of attention, the students are nonetheless an important component. There’s an opportunity to further ground the setting in local color through comparisons with the customs of the students. Many of those interactions take place over a warm meal. A shy Japanese youngster comments about the differences between how Italians and Japanese celebrate the Christmas season over preparations for a big feast. On another occasion, the hosts are mortified over how one American’s love for french fries has permeated the apartment with an unwanted greasy stench.

Overall, this approach makes for an easily accessible work. The story builds through the accumulation of intimate conversations, mundane observations, and tiny revelations. We come to realize what mini tragedies brought these individuals together, and appreciate the generous spirit that compels them to open their home to a varied and ever-changing flock of strangers. The meandering narrative is like taking a casual stroll through a friendly and welcoming neighborhood where the locals wouldn’t hesitate to talk about their lives over coffee and panino.

Translation: Joe Yamazaki

Touch-up Art/Lettering: Gia Cam Luc

Design: Fawn Lau

La Quinta Camera was a webcomic series that established Natsume Ono as a mangaka in Japan, but was translated by Viz after her later work Ristorante Paradiso. Nonetheless, one can see a number of commonalities between the two works. Ono displays an early fascination with the Western cultural milieu, particularly Italy. And just as in Ristorante Paradiso, the manga has a thing for adult males of a certain age. Even in her first story, Ono handles the lives of her characters with a deft and light touch, devoid of any cheap melodrama.

The manga does contain a few surprises. Considering Ono’s more mature minimalist style, La Quinta Camera’s art is practically primitive by comparison. Ono’s figures are blockier and more squat, almost reminiscent of early Cubism. Her lines are more uniform, as if she only used technical pens which produced a certain line thickness. This results in characters who are more archetypal in appearance. They’re recognizable primarily through larger features like their hairstyles, or preferred items of clothing.

Ono also uses a much simpler setup to make her story work. In the first chapter, a young woman from Denmark arrives at an unnamed Italian city and immediately suffers a series of mishaps. We learn that she’s here to learn the language. But after losing her personal belongings, getting lost, interacting with a few of the locals, and finally managing to find the language school, she’s directed to an apartment building for her room and board. To her surprise, she discovers that her hosts happen to be the very locals she met earlier on the street. If this were a more conventional story, the rest of the manga would be about the fish-out-of-water misadventures of the woman and her 4 eccentric roommates.

But this isn’t the case at all. In the next chapter, the woman has already moved out of the apartment and an artist has moved into the room. We learn that the owner has arranged with the school to rent the apartment’s 5th room to the school’s foreign students, who usually stay for a short period. Each chapter introduces a different student, and their outside perspective allows us to learn a little more about the 4 permanent residents in the apartment.

While they might not be the center of attention, the students are nonetheless an important component. There’s an opportunity to further ground the setting in local color through comparisons with the customs of the students. Many of those interactions take place over a warm meal. A shy Japanese youngster comments about the differences between how Italians and Japanese celebrate the Christmas season over preparations for a big feast. On another occasion, the hosts are mortified over how one American’s love for french fries has permeated the apartment with an unwanted greasy stench.

Overall, this approach makes for an easily accessible work. The story builds through the accumulation of intimate conversations, mundane observations, and tiny revelations. We come to realize what mini tragedies brought these individuals together, and appreciate the generous spirit that compels them to open their home to a varied and ever-changing flock of strangers. The meandering narrative is like taking a casual stroll through a friendly and welcoming neighborhood where the locals wouldn’t hesitate to talk about their lives over coffee and panino.

12/14/2016

More NonSense: And Love Is Love Is Love Is Love

Lin-Manuel Miranda gave a great 2016 Tony acceptance speech.

School Library Journal lists the Top 10 Graphic Novels for 2016.

Christopher Butcher lists some things he likes about Christmas.

Glen Weldon on that old chestnut, superheroes and Fascism.

Glen Weldon makes the case for dropping the label "graphic novel." While his arguments have merit, I suspect the term will stick around for a bit simply because the publishing industry seems attached to it.

R.I.P. Richard Kyle, the inventor of the term "graphic novel."

Magdalene Visaggio on the New Sincerity of the latest generation of comics creators.

Alli Joseph on the animated feature Moana, and Disney's long history of cultural appropriation.

This story about a young Supergirl fan has been making the rounds on the internet.

Kevin Wong on Peppermint Patty as feminist symbol.

12/11/2016

Shazam!: The Monster Society of Evil

By Jeff Smith

Colors: Steve Hamaker

Captain Marvel and Mary Marvel created by C. C. Beck, Bill Parker, Otto Binder, Marc Swayze.

No matter how successful, A rite of passage for American comics creators is that they prove their mettle by working on a property owned by DC or Marvel. Case in point, Jeff Smith had already established himself as the creator of the long-running and beloved comic book series Bone when DC tapped him in 2007 to work on a reimagining of Captain Marvel. The publisher had an undisputably lousy record when it came to their handling of the character. Their current comic was The Trials of Shazam!, the latest attempt to update a superhero known for being the embodiment of 40s whimsy with another grim ‘n’ gritty makeover. In the comic, an older Freddie Freeman, the former Captain Marvel Jr., overcomes a series of brutal ordeals to claim the powers of Captain Marvel after Billy Batson vacated the role in order to succeed the wizard Shazam. No one cared, and that version of Captain Marvel was quickly forgotten after the crossover event Final Crisis. Almost as unpopular was the evil Mary Marvel/Mary Batson who had inherited the powers of Black Adam. But many fans would have agreed that if anyone could make use of Captain Marvel’s classic elements while still appealing to modern sensibilities, it would have been Smith. With the 4 issue series Shazam!: The Monster Society of Evil, he proves to be up to the task.

The chief issues with DC’s treatment of Cap are that once he’s integrated into their shared universe, he loses his traditional primacy and becomes an auxiliary Superman. And as a perpetual C-lister, he’s particularly susceptible to the effects of DC’s habit of periodic soft reboots. Captain Marvel doesn’t have the illusion of growth engendered by a decades long history of continuous publication which benefit DC’s most well-known properties. So every cancellation followed by an attempt to reset and update him only underlines just how out-of-step he’s become with the rest of the company lineup. For a publisher that no longer believes in the inherent value of goofy adventures, DC appears to be constantly embarrassed that one of their most iconic, not to mention powerful, characters is also just a dumb kid from the 40s. No wonder turning the Marvel family members angsty or evil seemed like a good idea at the time.

Smith avoids these pitfalls by setting the story in its own milieu, far from the rest of DC’s madding crowd. It’s not a clear-cut solution. Smith starts out with another comic book retelling of Cap’s well-trod origins. But it’s quickly expedited, and he moves on with the main plot, an extra-dimensional invasion orchestrated by Mister Mind with the assistance of Doctor Sivana. When set next to the DC timeline, a comic featuring the classic supervillain team-up known as the Monster Society of Evil feels like a return to Cap’s roots.

But make no mistake, this is a Jeff Smith comic. His cartooning is very different from the DC House style, but Smith’s sinewy figures have a physicality quite unlike that of Cap’s original artist C. C. Beck. In contrast to Beck’s naive simplicity, Smith’s characters stoop, sweat, and strain with every effort. And his thick brushstrokes and moody blacks render a fictionalized New York less a gleaming urban jungle of glass and steel than an impressionistic dreamscape of dark alleyways and crumbling concrete structures. It’s the kind of place where a magic train would emerge from the inky depths to take a young Billy to see Shazam at the mysterious Rock of Eternity. And supernatural creatures like the Alligator Men and the tiger Talky Tawny exude a vague threat without looking entirely out of place.

Smith’s character designs feel particularly well-considered, due to the fact that he had to introduce several of them in a one-and-done story. His muscular Captain Marvel has a different persona than tiny, dirt-encrusted urchin Billy. This choice is a return to the original interpretation of the character. But Mary’s transformation is an unintended consequence of her brother’s, so her powers function in a different manner. And Mind and Sivana make their entrance due to a few of Billy’s unwise choices. Mind, the Alligator Men, and Tawny in particular showcase Smith’s facility for creature creation.

Smith injects some mild satire which pokes fun at the state of the War on Terror, grounding the comic in a specific time period. He may physically resemble a certain ornery Vice President, but Smith’s Sivana as business magnate turned Attorney General willing to sell out his country for a tidy profit has weirdly become more pertinent within the last month. Then again, he did promise that this wasn’t the last we’d hear of him.

Colors: Steve Hamaker

Captain Marvel and Mary Marvel created by C. C. Beck, Bill Parker, Otto Binder, Marc Swayze.

No matter how successful, A rite of passage for American comics creators is that they prove their mettle by working on a property owned by DC or Marvel. Case in point, Jeff Smith had already established himself as the creator of the long-running and beloved comic book series Bone when DC tapped him in 2007 to work on a reimagining of Captain Marvel. The publisher had an undisputably lousy record when it came to their handling of the character. Their current comic was The Trials of Shazam!, the latest attempt to update a superhero known for being the embodiment of 40s whimsy with another grim ‘n’ gritty makeover. In the comic, an older Freddie Freeman, the former Captain Marvel Jr., overcomes a series of brutal ordeals to claim the powers of Captain Marvel after Billy Batson vacated the role in order to succeed the wizard Shazam. No one cared, and that version of Captain Marvel was quickly forgotten after the crossover event Final Crisis. Almost as unpopular was the evil Mary Marvel/Mary Batson who had inherited the powers of Black Adam. But many fans would have agreed that if anyone could make use of Captain Marvel’s classic elements while still appealing to modern sensibilities, it would have been Smith. With the 4 issue series Shazam!: The Monster Society of Evil, he proves to be up to the task.

The chief issues with DC’s treatment of Cap are that once he’s integrated into their shared universe, he loses his traditional primacy and becomes an auxiliary Superman. And as a perpetual C-lister, he’s particularly susceptible to the effects of DC’s habit of periodic soft reboots. Captain Marvel doesn’t have the illusion of growth engendered by a decades long history of continuous publication which benefit DC’s most well-known properties. So every cancellation followed by an attempt to reset and update him only underlines just how out-of-step he’s become with the rest of the company lineup. For a publisher that no longer believes in the inherent value of goofy adventures, DC appears to be constantly embarrassed that one of their most iconic, not to mention powerful, characters is also just a dumb kid from the 40s. No wonder turning the Marvel family members angsty or evil seemed like a good idea at the time.

Smith avoids these pitfalls by setting the story in its own milieu, far from the rest of DC’s madding crowd. It’s not a clear-cut solution. Smith starts out with another comic book retelling of Cap’s well-trod origins. But it’s quickly expedited, and he moves on with the main plot, an extra-dimensional invasion orchestrated by Mister Mind with the assistance of Doctor Sivana. When set next to the DC timeline, a comic featuring the classic supervillain team-up known as the Monster Society of Evil feels like a return to Cap’s roots.

But make no mistake, this is a Jeff Smith comic. His cartooning is very different from the DC House style, but Smith’s sinewy figures have a physicality quite unlike that of Cap’s original artist C. C. Beck. In contrast to Beck’s naive simplicity, Smith’s characters stoop, sweat, and strain with every effort. And his thick brushstrokes and moody blacks render a fictionalized New York less a gleaming urban jungle of glass and steel than an impressionistic dreamscape of dark alleyways and crumbling concrete structures. It’s the kind of place where a magic train would emerge from the inky depths to take a young Billy to see Shazam at the mysterious Rock of Eternity. And supernatural creatures like the Alligator Men and the tiger Talky Tawny exude a vague threat without looking entirely out of place.

Smith’s character designs feel particularly well-considered, due to the fact that he had to introduce several of them in a one-and-done story. His muscular Captain Marvel has a different persona than tiny, dirt-encrusted urchin Billy. This choice is a return to the original interpretation of the character. But Mary’s transformation is an unintended consequence of her brother’s, so her powers function in a different manner. And Mind and Sivana make their entrance due to a few of Billy’s unwise choices. Mind, the Alligator Men, and Tawny in particular showcase Smith’s facility for creature creation.

Smith injects some mild satire which pokes fun at the state of the War on Terror, grounding the comic in a specific time period. He may physically resemble a certain ornery Vice President, but Smith’s Sivana as business magnate turned Attorney General willing to sell out his country for a tidy profit has weirdly become more pertinent within the last month. Then again, he did promise that this wasn’t the last we’d hear of him.

12/07/2016

12/04/2016

Wonder Woman: The True Amazon

By Jill Thompson

Letters: Jason Arthur

Letters: Jason Arthur

Wonder Woman created by William Moulton Marston, H. G. Peter, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, Olive Byrne.

Wonder Woman’s origin story went through considerable modifications with the New 52 era. Changes that were so controversial among her fans that the story has again been altered to coincide with this year’s Rebirth event. To make things even more complicated, DC has released a few comics that don’t operate within the publisher’s main continuity. There’s the ongoing Wonder Woman ‘77, an adaptation that continues the campy 70s television series. Digital first comic The Legend of Wonder Woman. And the version found in DC Comics Bombshells. There’s also a pair of standalone graphic novels retelling her origin: Wonder Woman: Earth One by Grant Morrison. And most recently, Wonder Woman: The True Amazon, by Jill Thompson. If someone had to choose, Thompson’s comic might be the most accessible to newer and younger readers.

While technically still a comic, The True Amazon feels like it could have been easily converted into an illustrated children’s book. Thompson brings to the table her signature watercolors, which makes The True Amazon visually unlike any of DC’s other current offerings. It looks and feels more like traditional literary fare. Thompson’s narrative panels are plentiful and rather text-heavy for a modern comic. The third person narration contained within tells the story often in parallel with the art, a rather old-fashioned comics device by today’s standard. Thompson even uses the occasional thought balloon to capture the young Princess Diana’s inner monologue. Nevertheless, what emerges is a vividly colorful portrayal of Amazon society. One that feels ancient and rustic, but still alive.

That classical aesthetic is central to Thompson’s peculiar interpretation. She’s chosen not to retell WW’s origin as a superhero story, but as a tragic fairy tale. The comic begins familiarly enough with the Amazon nation of the Bronze Age finding itself in conflict with the rest of a chauvinistic ancient Greece. The King of Mycenae entreats the hero Herakles to steal the Golden Girdle of the Amazon Queen Hippolyta. But the Amazons escape with the help of Hera, Queen of the gods, and god of the sea Poseidon. They settle on the magical island of Themyscira, where Hippolyta fashions a statue of a baby girl. The statue is brought to life by the gods and grows into Princess Diana. So far, so mostly in keeping with the narrative promoted by creator William Moulton Marston.

Thompson however chooses to dispense with all the fantasy elements that would contradict the Bronze Age milieu. There are no giant kangas, no Purple Ray, Invisible Jet, the Bullets and Bracelets test, or bondage of any sort. In short, none of the cool ideas concocted by Marston and company. Actually, once the Amazons settle on Themyscira, the march of history simply doesn’t affect them. There’s no World War II, Nazi’s, or even a Steve Trevor in sight. And forget about Etta Candy and the Holliday Girls. There’s one throwaway line which admits that the Amazons can still observe the outside world through a magic scrying pool. But no one actually talks about it. As a result, the immortal Amazons live inside a proverbial time warp. An eternal, unchanging present. As far as the reader is concerned, the story may as well still be taking place in the Bronze Age.

The one disruptive force found in this idyllic setting is Diana. Blessed by the gods with abilities that surpass her fellow Amazons and the only daughter to the Queen, Diana is doted upon by almost everyone. Both Thompson and Morrison both portray her as growing up spoiled by her sheltered existence. But whereas Morrison’s Diana retains an incipient curiosity of the outside world which is suddenly jumpstarted by her unexpected encounter with Steve, Thompson’s Diana remains perfectly happy to continue living within her bubble. She develops into the very image of the selfish, vain, entitled, princess. And in place of her love for Steve, Diana develops a grudging friendship with the one Amazon on the island who isn’t impressed at all with her. But apropos of the comic’s fairy tale approach, the relationship is doomed from the start to end in a most unhappy manner.

This bratty version of Diana is someone who many younger readers will likely be able to find very relatable. She’s confident, headstrong, tough, brave, loyal, not to mention an extremely powerful kid who gets her way, most of the time. The built-in morale that growing up involves learning to be more considerate to the needs of others is a message that will meet the approval of most parents. And Thompson’s luminous watercolors are an obvious draw. Those seeking a more typical superhero story should look at the other comics mentioned at the top of this post. And The True Amazon won’t quite satisfy every WW fan, since the disappearance of Marston’s weirder elements means that his feminine utopian agenda gets lost by the end of the book. But a tale of a young Diana forming a close relationship with another woman is a not insignificant way to update her origin.

While technically still a comic, The True Amazon feels like it could have been easily converted into an illustrated children’s book. Thompson brings to the table her signature watercolors, which makes The True Amazon visually unlike any of DC’s other current offerings. It looks and feels more like traditional literary fare. Thompson’s narrative panels are plentiful and rather text-heavy for a modern comic. The third person narration contained within tells the story often in parallel with the art, a rather old-fashioned comics device by today’s standard. Thompson even uses the occasional thought balloon to capture the young Princess Diana’s inner monologue. Nevertheless, what emerges is a vividly colorful portrayal of Amazon society. One that feels ancient and rustic, but still alive.

That classical aesthetic is central to Thompson’s peculiar interpretation. She’s chosen not to retell WW’s origin as a superhero story, but as a tragic fairy tale. The comic begins familiarly enough with the Amazon nation of the Bronze Age finding itself in conflict with the rest of a chauvinistic ancient Greece. The King of Mycenae entreats the hero Herakles to steal the Golden Girdle of the Amazon Queen Hippolyta. But the Amazons escape with the help of Hera, Queen of the gods, and god of the sea Poseidon. They settle on the magical island of Themyscira, where Hippolyta fashions a statue of a baby girl. The statue is brought to life by the gods and grows into Princess Diana. So far, so mostly in keeping with the narrative promoted by creator William Moulton Marston.

Thompson however chooses to dispense with all the fantasy elements that would contradict the Bronze Age milieu. There are no giant kangas, no Purple Ray, Invisible Jet, the Bullets and Bracelets test, or bondage of any sort. In short, none of the cool ideas concocted by Marston and company. Actually, once the Amazons settle on Themyscira, the march of history simply doesn’t affect them. There’s no World War II, Nazi’s, or even a Steve Trevor in sight. And forget about Etta Candy and the Holliday Girls. There’s one throwaway line which admits that the Amazons can still observe the outside world through a magic scrying pool. But no one actually talks about it. As a result, the immortal Amazons live inside a proverbial time warp. An eternal, unchanging present. As far as the reader is concerned, the story may as well still be taking place in the Bronze Age.

The one disruptive force found in this idyllic setting is Diana. Blessed by the gods with abilities that surpass her fellow Amazons and the only daughter to the Queen, Diana is doted upon by almost everyone. Both Thompson and Morrison both portray her as growing up spoiled by her sheltered existence. But whereas Morrison’s Diana retains an incipient curiosity of the outside world which is suddenly jumpstarted by her unexpected encounter with Steve, Thompson’s Diana remains perfectly happy to continue living within her bubble. She develops into the very image of the selfish, vain, entitled, princess. And in place of her love for Steve, Diana develops a grudging friendship with the one Amazon on the island who isn’t impressed at all with her. But apropos of the comic’s fairy tale approach, the relationship is doomed from the start to end in a most unhappy manner.

This bratty version of Diana is someone who many younger readers will likely be able to find very relatable. She’s confident, headstrong, tough, brave, loyal, not to mention an extremely powerful kid who gets her way, most of the time. The built-in morale that growing up involves learning to be more considerate to the needs of others is a message that will meet the approval of most parents. And Thompson’s luminous watercolors are an obvious draw. Those seeking a more typical superhero story should look at the other comics mentioned at the top of this post. And The True Amazon won’t quite satisfy every WW fan, since the disappearance of Marston’s weirder elements means that his feminine utopian agenda gets lost by the end of the book. But a tale of a young Diana forming a close relationship with another woman is a not insignificant way to update her origin.

11/30/2016

More NonSense: The Best Of 2016

|

| Andrew Aydin, John Lewis and Nate Powell (via National Book Foundation) |

Amazon lists the top 20 graphic novels for 2016.

Michael Cavna lists the best graphic novels of 2016.

Charlotte McDuffie on her late husband Dwayne McDuffie and the awards established in his memory.

Sacha Mardou on the female characters created by Dan Clowes.

Zulkiflee Anwar Unlhaque aka Zunar arrested again, this time for sedition against Malaysian Prime Minister.

Alanna Bennett on the growing divide between Harry Potter fans and their beloved franchise. Perhaps the most infamous recent example was the charge of cultural appropriation over J.K. Rowling's History of Magic in North America.

But not everyone is agitating for greater inclusiveness. Angelica Jade Bastién covers the growing racist backlash from some parts of superhero fandom. Both trends could probably be connected to a larger national conversation. But I wonder what this says about how franchises are created at different points in time and how different kinds of individuals end up gravitating towards them?

Alex Vadukul on Hong Kong's first female kung fu star, Angela Mao. Most people will recognize her as Su Lin in Enter the Dragon.

Erin Gloria Ryan on the surging demand for self-defence classes since Nov 8. These types of articles are usually written when people worry about a perceived increase in violent crime or terrorism while focusing on male students and instructors. But marginalized individuals such as women, minorities, and the LGBTQ community have always had their own specific self defence needs.

Sean Kleefeld, Tyler Amato, John Seavey, myself are ready to say goodbye to 2016.

11/27/2016

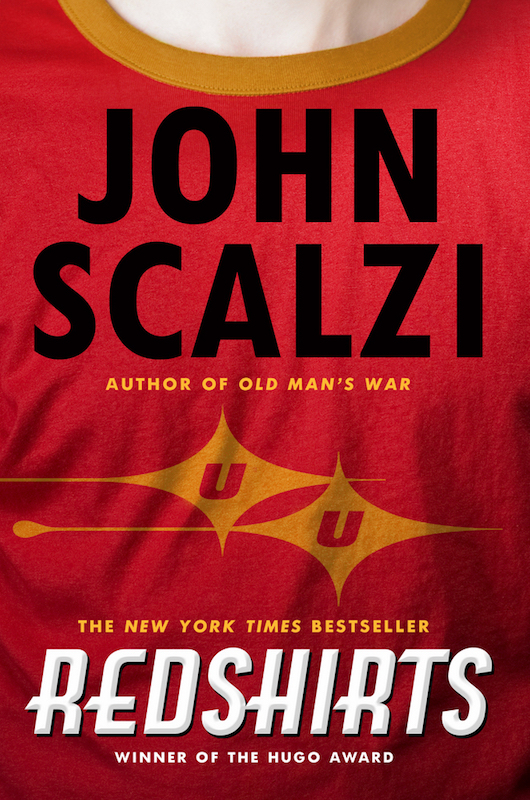

50th Trek: Redshirts

In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas

By John Scalzi

One inescapable part of being a 21st century consumer of popular genre entertainment is the impossibility of ignoring any discussion about the multitude of tropes it generates. Televised science fiction is no exception in this regard. And Star Trek is often credited with inventing, or at the very least popularizing, many sci-fi tropes. As I pointed out in my look at The Physics of Star Trek, the venerable franchise has already generated a considerable amount of discussion from fans possessing differing academic credentials. But the most accessible way to examine the unreality of fiction is through the use of metafictional devices. Irony and self-reflection are the order of the day, especially when dealing with works that are already decades old. What’s the point anymore in denying that one isn’t watching or reading a work of fiction? Named after one of Trek’s most well known conventions, Redshirts begins very much the way most fans would probably expect. But in order to fill over 300 pages, author John Scalzi pushes the conceit to its logical extreme.

That conceit was already touched on in the 1999 comedy Galaxy Quest. In the film, the cast of an old sci-fi show are made to reprise their roles for the benefit of a group of naive aliens who've confused the show for footage of real events. As a result actor Guy Fleegman (played by Sam Rockwell) is filled with fear that he will die at any moment because his role on the show was a redshirt - a random crewmember who looses his life in one episode. Guy’s terror mounts with every dangerous situation they face until he’s eventually convinced by one of the cast regulars that he could be instead playing the plucky comic relief. He undergoes a quick personal transformation, especially after someone else dies dramatically in his place.

In the novel, a group of ensigns working for the intergalactic organization named the Universal Union (affectionately called the Dub U) have just been assigned to the starship Intrepid. The ensigns treat this like any other assignment until they all realize they’re replacing dead crewmembers. In fact, the Intrepid has a notoriously high turnover rate because crewmembers keep getting killed on every away mission. Even odder, every mission is composed of at least one bridge officer. While they might occasionally endure bodily injury, they’re apparently immune to death. The bridge officers are entirely oblivious to this oddity even when it's pointed out to them. But the rest of the crew lives in a state of constant terror, just like Guy. They make themselves scarce whenever one of the officers are nearby. And they’ve developed a bizarre set of superstitious behaviors designed to minimize the body count, based on which officer they’re accompanying on a mission.

If this was the full extent of the novel, it would be nothing more than a clever parody of a famous television show. But these redshirts refuse to be just glorified extras, they want to be the heroes of their own story. So they make a point of getting to the root cause of this enigma. And without giving away too much, they’re eventually confronted with the absurdly fictional nature of their own existence. Scalzi's redshirts are actually competent scientists, which makes their observations about the universe they live in all the more painfully ironic.

This draws attention to the paradox of Star Trek's appeal. Like many science fiction authors, Scalzi is pretty critical about how science is often portrayed on televised sci-fi. It’s rules are often inconsistent and continuosly altered to serve the narrative. The redshirts often give voice this analysis. A bridge officer who’s an obvious analog for Pavel Chekov is exposed to a life threatening disease, but is saved at the last moment by a literal magic box. He’s horribly mangled by killer robots, only to fully recover a few days later. When the redshirts debate about a possible method for time travel, they note that the only reason it could possibly work is if the procedure included one of the bridge officers. And they’re completely mystified by the sheer number of nonsensical deaths suffered by the Intrepid’s crewmembers: Longranian ice sharks, Borgovian land worms, Pornathic crabs. Weirdness piled upon weirdness.

Star Trek’s fanciful vision of space exploration looks more anachronistic today than it would have back in the 1960s. And yet the franchise is often cited as an inspiration that made actual space exploration a reality. The science might be iffy, but its optimistic view of the future proved to be enduring. Even Scalzi’s critique is made from a position of affection for the television show. His protagonists have an unfortunate tendency towards quippishness, but they’re an intelligent and mostly sympathetic bunch who work together just as well as any Starfleet crew. Enough so that when one of them dies, the demise comes across as wasteful.

Redshirts runs out of plot before the book ends. The last third of the book is a lengthy meditation on the nature of fiction and its connection to reality, written as 3 lengthy codas. Scalzi explores the intimate relationship between writers and their creations. The fear writers have that the characters they hurt and kill on the page are truly suffering somewhere out there is thematically similar to the 2006 film Stranger than Fiction. The codas are tonally dissonant and focus on a completely different set of characters, so that it’s best to think of them not as the conclusion to the main story, but as a separate, if related, body of work. Unnecessary perhaps, but one that rounds out Scalzi’s own metafictional examination. Overall, he took kind of an awfully crazy journey to get there.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas

By John Scalzi

One inescapable part of being a 21st century consumer of popular genre entertainment is the impossibility of ignoring any discussion about the multitude of tropes it generates. Televised science fiction is no exception in this regard. And Star Trek is often credited with inventing, or at the very least popularizing, many sci-fi tropes. As I pointed out in my look at The Physics of Star Trek, the venerable franchise has already generated a considerable amount of discussion from fans possessing differing academic credentials. But the most accessible way to examine the unreality of fiction is through the use of metafictional devices. Irony and self-reflection are the order of the day, especially when dealing with works that are already decades old. What’s the point anymore in denying that one isn’t watching or reading a work of fiction? Named after one of Trek’s most well known conventions, Redshirts begins very much the way most fans would probably expect. But in order to fill over 300 pages, author John Scalzi pushes the conceit to its logical extreme.

That conceit was already touched on in the 1999 comedy Galaxy Quest. In the film, the cast of an old sci-fi show are made to reprise their roles for the benefit of a group of naive aliens who've confused the show for footage of real events. As a result actor Guy Fleegman (played by Sam Rockwell) is filled with fear that he will die at any moment because his role on the show was a redshirt - a random crewmember who looses his life in one episode. Guy’s terror mounts with every dangerous situation they face until he’s eventually convinced by one of the cast regulars that he could be instead playing the plucky comic relief. He undergoes a quick personal transformation, especially after someone else dies dramatically in his place.

In the novel, a group of ensigns working for the intergalactic organization named the Universal Union (affectionately called the Dub U) have just been assigned to the starship Intrepid. The ensigns treat this like any other assignment until they all realize they’re replacing dead crewmembers. In fact, the Intrepid has a notoriously high turnover rate because crewmembers keep getting killed on every away mission. Even odder, every mission is composed of at least one bridge officer. While they might occasionally endure bodily injury, they’re apparently immune to death. The bridge officers are entirely oblivious to this oddity even when it's pointed out to them. But the rest of the crew lives in a state of constant terror, just like Guy. They make themselves scarce whenever one of the officers are nearby. And they’ve developed a bizarre set of superstitious behaviors designed to minimize the body count, based on which officer they’re accompanying on a mission.

If this was the full extent of the novel, it would be nothing more than a clever parody of a famous television show. But these redshirts refuse to be just glorified extras, they want to be the heroes of their own story. So they make a point of getting to the root cause of this enigma. And without giving away too much, they’re eventually confronted with the absurdly fictional nature of their own existence. Scalzi's redshirts are actually competent scientists, which makes their observations about the universe they live in all the more painfully ironic.

This draws attention to the paradox of Star Trek's appeal. Like many science fiction authors, Scalzi is pretty critical about how science is often portrayed on televised sci-fi. It’s rules are often inconsistent and continuosly altered to serve the narrative. The redshirts often give voice this analysis. A bridge officer who’s an obvious analog for Pavel Chekov is exposed to a life threatening disease, but is saved at the last moment by a literal magic box. He’s horribly mangled by killer robots, only to fully recover a few days later. When the redshirts debate about a possible method for time travel, they note that the only reason it could possibly work is if the procedure included one of the bridge officers. And they’re completely mystified by the sheer number of nonsensical deaths suffered by the Intrepid’s crewmembers: Longranian ice sharks, Borgovian land worms, Pornathic crabs. Weirdness piled upon weirdness.

Star Trek’s fanciful vision of space exploration looks more anachronistic today than it would have back in the 1960s. And yet the franchise is often cited as an inspiration that made actual space exploration a reality. The science might be iffy, but its optimistic view of the future proved to be enduring. Even Scalzi’s critique is made from a position of affection for the television show. His protagonists have an unfortunate tendency towards quippishness, but they’re an intelligent and mostly sympathetic bunch who work together just as well as any Starfleet crew. Enough so that when one of them dies, the demise comes across as wasteful.

Redshirts runs out of plot before the book ends. The last third of the book is a lengthy meditation on the nature of fiction and its connection to reality, written as 3 lengthy codas. Scalzi explores the intimate relationship between writers and their creations. The fear writers have that the characters they hurt and kill on the page are truly suffering somewhere out there is thematically similar to the 2006 film Stranger than Fiction. The codas are tonally dissonant and focus on a completely different set of characters, so that it’s best to think of them not as the conclusion to the main story, but as a separate, if related, body of work. Unnecessary perhaps, but one that rounds out Scalzi’s own metafictional examination. Overall, he took kind of an awfully crazy journey to get there.

Labels:

Commentary,

fantasy,

Prose,

science,

Star Trek,

television

11/23/2016

Webcomic: The Electoral College Isn't Working. Here's How it Might Die

Go to: The Nib, by Andy Warner

11/20/2016

Ether #1

Story: Matt Kindt

Art: David Rubin

Variant Cover: Jeff Lemire

Coming on the heels of Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange movie, the completely unrelated Ether promises the reader yet another magical romp through a multiverse populated by odd beings and even odder technologies. This is exactly the kind of comic book series one would expect from author Matt Kindt, known for being the creator of the hyper intricate ur-conspiracy Mind MGMT and the ongoing undersea murder mystery Dept H. But the comic displays a lighthearted approach not usually found in his past works. This owes a lot to Kindt’s artistic collaborator David Rubin. It’s only during the last few pages that the comic transitions into something more recognizably like Kindt when the atmosphere becomes more oppressive and terrifying.

Rubin’s art resembles that of Rafael Grampá, and that quality of cartoonish exaggeration is essential to the comic’s world-building. The first alien encountered is a gruff, giant purple ape-like creature called Glum, the self-described gatekeeper to the alternate worlds of the multiverse. Other weird denizens include the Bloody Screecher, a bird resembling a canary that wears an unsettling, toothy grin. Or the Magic Bullet, a projectile that resembles an unborn fetus. While Rubin doesn’t spend nearly enough time exploring the streets of Agartha, the capital city of the magical world known as Ether, his bathing the setting in an otherworldly combination of vibrant ruby, emerald and cerulean hues is charming enough.

But the true oddball in this place is Earthling and main protagonist Boone Dias, who dresses like a more dashing Ghostbuster and whose personality could be described as a mix of Egon Spengler, Sherlock Holmes, and Indiana Jones. Boone discovered the Ether years ago and has since refashioned himself as the mighty explorer of an exotic new world. He’s apt to use adjectives like “beautiful” and “fascinating” when describing the wonders of the Ether. And like so many white males before him, he’s more than a little condescending towards the natives and what are to him their backward superstitions. Nonetheless, the rulers of Agartha admire his rigorous scientific mind, and he’s been often called upon by them to solve various crimes. Boone has even cultivated a rivalry with a would-be Moriarity figure whom he grandiosely describes as his most dangerous adversary.

And the Ether isn’t half as interesting as the opulent detail found in the comic’s twist ending. Rubin’s illustration of present-day Earth makes it into a dystopian nightmare. And even Boone himself reacts by seeming to shrink in stature. But the reader has only seen the world through his eyes. How much of his experience is real or imagined? Or the product of evil machinations of yet-unseen parties? Kindt has set up another twisted puzzle for us to untangle.

Art: David Rubin

Variant Cover: Jeff Lemire

Coming on the heels of Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange movie, the completely unrelated Ether promises the reader yet another magical romp through a multiverse populated by odd beings and even odder technologies. This is exactly the kind of comic book series one would expect from author Matt Kindt, known for being the creator of the hyper intricate ur-conspiracy Mind MGMT and the ongoing undersea murder mystery Dept H. But the comic displays a lighthearted approach not usually found in his past works. This owes a lot to Kindt’s artistic collaborator David Rubin. It’s only during the last few pages that the comic transitions into something more recognizably like Kindt when the atmosphere becomes more oppressive and terrifying.

Rubin’s art resembles that of Rafael Grampá, and that quality of cartoonish exaggeration is essential to the comic’s world-building. The first alien encountered is a gruff, giant purple ape-like creature called Glum, the self-described gatekeeper to the alternate worlds of the multiverse. Other weird denizens include the Bloody Screecher, a bird resembling a canary that wears an unsettling, toothy grin. Or the Magic Bullet, a projectile that resembles an unborn fetus. While Rubin doesn’t spend nearly enough time exploring the streets of Agartha, the capital city of the magical world known as Ether, his bathing the setting in an otherworldly combination of vibrant ruby, emerald and cerulean hues is charming enough.

But the true oddball in this place is Earthling and main protagonist Boone Dias, who dresses like a more dashing Ghostbuster and whose personality could be described as a mix of Egon Spengler, Sherlock Holmes, and Indiana Jones. Boone discovered the Ether years ago and has since refashioned himself as the mighty explorer of an exotic new world. He’s apt to use adjectives like “beautiful” and “fascinating” when describing the wonders of the Ether. And like so many white males before him, he’s more than a little condescending towards the natives and what are to him their backward superstitions. Nonetheless, the rulers of Agartha admire his rigorous scientific mind, and he’s been often called upon by them to solve various crimes. Boone has even cultivated a rivalry with a would-be Moriarity figure whom he grandiosely describes as his most dangerous adversary.

And the Ether isn’t half as interesting as the opulent detail found in the comic’s twist ending. Rubin’s illustration of present-day Earth makes it into a dystopian nightmare. And even Boone himself reacts by seeming to shrink in stature. But the reader has only seen the world through his eyes. How much of his experience is real or imagined? Or the product of evil machinations of yet-unseen parties? Kindt has set up another twisted puzzle for us to untangle.

11/14/2016

The Gods Lie

Kamisama ga Uso wo Tsuku

By Kaori Ozaki

Translation: Melissa Tanaka

A complicated truth that every child eventually has to figure out is that all the adults they look up to are flawed individuals who will even betray their trust from time to time. It’s a painful lesson to learn, even within the most stable and supportive family environment. But the main protagonists of The Gods Lie are brought together by similar personal loss, which renders the lesson all the more heartwrenching during the latter half of the book. It’s a heady mix of budding romance, death, and abandonment, compressed into an intimate domestic drama that takes place over the course of one summer. But Kaori Ozaki uses a delicate touch that preserves the essential sweetness of her characters.

The two youngsters at the center of the story start out as typical manga archetypes. 6th grader Natsuru Nanao loves soccer. But he hasn’t yet learned to comport himself around girls, and they’ve in turn mostly snubbed him. But he takes notice of reserved tall girl Rio Suzumura. The two strike up a friendship when Natsuru asks her to adopt an abandoned kitten he found under a bridge, since he's unable to keep it. Rio and her younger brother Yuuta live alone and unsupervised in a rickety old house because their father apparently spends long stretches in the Pacific Northwest as a commercial fisherman. This strikes a chord with Natsuru, since he’s being currently raised as an only child by an overworked single mother.

Matters come to a head when Natsuru’s beloved coach is hospitalized and he finds himself clashing with the new coach’s diametrically different teaching style. When summer break arrives, he lies to his mom and ditches soccer camp. With nowhere else to go, he ends up moving into Rio and Yuuta's house. Now, manga readers will recognize some of the tropes of this living arrangement. There are the awkwardly intimate sleeping situations, Japanese bathing humor, learning how to socialize at the dining table. There’s even scenes involving the requisite summer festival and visit to the beach. On the surface, Ozaki’s own controlled linework doesn't vary much from the conventional seinen style.

However, these elements aren’t exploited to generate the usual silly misunderstandings found in much commercial manga. Both Rio and Natsuru approach playing house with the quiet earnestness of children struggling to find their place in the world. Both are able to find a sense of purpose in their lives by substituting for teach others absent parental figures. As they settle into their respective roles, a tranquility they’ve been desperately craving descends on the household. It isn’t long before both feel something approaching love.

Summer has to end eventually, and a series of unexpected revelations throws the makeshift family into turmoil. Rio and Natsuru’s house playing serves as a temporary respite from the actual complications adults face in daily life. Coming to terms with this messiness is an inevitable part of growing up. But as Rio and Natsuru also learn, so is keeping as much of the messiness at bay for the sake of protecting the happiness of the people under their care.

By Kaori Ozaki

Translation: Melissa Tanaka

A complicated truth that every child eventually has to figure out is that all the adults they look up to are flawed individuals who will even betray their trust from time to time. It’s a painful lesson to learn, even within the most stable and supportive family environment. But the main protagonists of The Gods Lie are brought together by similar personal loss, which renders the lesson all the more heartwrenching during the latter half of the book. It’s a heady mix of budding romance, death, and abandonment, compressed into an intimate domestic drama that takes place over the course of one summer. But Kaori Ozaki uses a delicate touch that preserves the essential sweetness of her characters.

The two youngsters at the center of the story start out as typical manga archetypes. 6th grader Natsuru Nanao loves soccer. But he hasn’t yet learned to comport himself around girls, and they’ve in turn mostly snubbed him. But he takes notice of reserved tall girl Rio Suzumura. The two strike up a friendship when Natsuru asks her to adopt an abandoned kitten he found under a bridge, since he's unable to keep it. Rio and her younger brother Yuuta live alone and unsupervised in a rickety old house because their father apparently spends long stretches in the Pacific Northwest as a commercial fisherman. This strikes a chord with Natsuru, since he’s being currently raised as an only child by an overworked single mother.

Matters come to a head when Natsuru’s beloved coach is hospitalized and he finds himself clashing with the new coach’s diametrically different teaching style. When summer break arrives, he lies to his mom and ditches soccer camp. With nowhere else to go, he ends up moving into Rio and Yuuta's house. Now, manga readers will recognize some of the tropes of this living arrangement. There are the awkwardly intimate sleeping situations, Japanese bathing humor, learning how to socialize at the dining table. There’s even scenes involving the requisite summer festival and visit to the beach. On the surface, Ozaki’s own controlled linework doesn't vary much from the conventional seinen style.

However, these elements aren’t exploited to generate the usual silly misunderstandings found in much commercial manga. Both Rio and Natsuru approach playing house with the quiet earnestness of children struggling to find their place in the world. Both are able to find a sense of purpose in their lives by substituting for teach others absent parental figures. As they settle into their respective roles, a tranquility they’ve been desperately craving descends on the household. It isn’t long before both feel something approaching love.

Summer has to end eventually, and a series of unexpected revelations throws the makeshift family into turmoil. Rio and Natsuru’s house playing serves as a temporary respite from the actual complications adults face in daily life. Coming to terms with this messiness is an inevitable part of growing up. But as Rio and Natsuru also learn, so is keeping as much of the messiness at bay for the sake of protecting the happiness of the people under their care.

11/12/2016

More NonSense: The Trump Effect

|

| 10 Cartoonists React to Trump Winning the Election: Kendra Wells |

On a note more pertinent to this blog, Trump's presidency will most probably have a chilling effect on intellectual enquiry and creative expression, especially in the already fragile comics industry. Here's more commentary from Sean Kleefeld, Tom Spurgeon, Heidi MacDonald, Tim Holder, Humberto Ramos, ComicsAlliance,

Did you know that Peter Kuper drew a comic predicting the Donald Trump Wall for Heavy Metal Magazine in the July 1990 issue?

Seth T. Hahne lists the 75 Best Comics by Women.

J. Scott Campbell redraws Riri Williams, after dismissing the negative reactions towards his original cover illustration for Invincible Iron Man.

R.I.P. Leonard Cohen (September 21, 1934 – November 7, 2016).

11/09/2016

11/08/2016

Map: AuthaGraph World Map

Go to: Good Design Award, by Hajime Narukawa (via William Turton)

11/05/2016

Video: Monsoon III

Go to: Vimeo, by Mike Olbinski (via Phil Plait)

11/02/2016

More Nonsense: Ms. Marvel Will Save You Now

|

| Three Marvel interpretations of Kamala Khan surround fan Meevers Desu as Ms. Marvel at the Denver Comic Con. |

Barbara Calderón interviews Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez.

Sean T. Collins lists the greatest graphic novels of all time.

Heidi MacDonald on the contradiction that is Wonder Woman as a U.N. Honorary Ambassador.

R.I.P. Jack Chick (April 13, 1924-October 23, 2016). Tributes by Benito Cereno, Sean Kleefeld, Heidi MacDonald, Joe McCulloch,

Just a reminder: Scott Adams is nuts.

Charles Russo deciphers Bruce Lee vs. Wong Jack Man.

Lucasfilm sues New York Jedi over trademark infringement. I've been wandering when Lucas/Disney would go after any of the numerous lightsaber academies.

Labels:

alternative,

black and white,

cartoon,

Commentary,

fighting arts,

gender roles,

Gilbert Hernandez,

Jack Chick,

Jaime Hernandez,

Kamala Khan,

Ms. Marvel,

politics,

race,

religion,

Scott Adams,

Star Wars,

superhero,

Wonder Woman

10/30/2016

50th Trek: Star Trek: Boldly Go #1 & Star Trek: Waypoint #1

In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

It occurred to me that I haven’t discussed any of the comic books being published to honor the occasion of Star Trek’s 50th anniversary. So here are two titles from IDW. I’ve found the marketing surrounding this milestone to be strangely anemic, and I wasn’t aware of these comics until the last few days. How pitiful is that?

Star Trek: Boldly Go #1

Story: Mike Johnson

Art: Tony Shasteen

Colors: Davide Mastrolonardo

Letters: AndWorld Designs

[Spoiler Alert for Star Trek Beyond]

An oft-repeated truism among fans is that Star Trek is better suited for television than cinema. The reason usually given by them is that Trek’s brand of introspective storytelling isn’t perfectly compatible with the spectacle often associated with the silver screen. But a simpler reason is that Trek was originally designed to be an episodic TV show. Over the course of its initial run, the show acquired a rather complicated history. This history would become a rich backstory referenced by future films, for all intents turning them into longer, more expensive television episodes possessing much better production values.

This close connection between the two parts of the franchise was somewhat ruptured with the Kelvin timeline. The venerable Leonard Nimoy was on hand for the 2009 cinematic reboot to inform the new cast (and remind the audience) about a continuity that had now become a sign for what could have been. Now unable to directly use the original timeline, the two sequels would sometimes refer to new, never before filmed events. In lieu of a TV show, IDW would launch a new comic book series to helpfully fill-in the events that took place between the films. Unfortunately, this is the best that fans can expect of the U.S.S. Enterprise crew of the Kelvin timeline. It’s highly unlikely that this particular cast would agree to meet the additional demands of shooting a television series. And even the film sequels still leaned heavily on Nimoy and nostalgia for the original timeline to lend emotional heft to their proceedings. The comic books still felt relatively incidental to the films.

But while the relationship between print and screen may be one-sided, IDW is committed for now to keeping the Kelvin timeline alive between film launches. Star Trek: Boldly Go is a continuation of the comic book series, only now under a new title. The comic picks up where Star Trek Beyond left off. The film notoriously destroyed the Enterprise yet again, only to promise that everyone would soon reunite with a brand new starship. This series gets to tell what happened to them in the meantime.

All in all, this is an entertaining, if conventional, reintroduction to the main characters. Just like the cast of the Original Series from the early films, James Kirk and company have been scattered to different Starfleet commissions throughout Federation space. Unlike TOS Kirk, the new Kirk has decided not to pursue the promotion to the post of admiral. That’s a shame, since I found that one of the more visually cooler settings of STB was the space station Yorktown. Kirk has decided instead to accept the assignment of “interim captain” of another starship, and he’s accompanied by the good doctor Leonard “Bones” McCoy and the always eager ensign Pavel Chekov. I'll admit, his presence on the ship is particularly bittersweet for reasons that have nothing to do with the comic.

Mike Johnson and Tony Shasteen capture the tone and look of the films’ cast while integrating a few elements from the original timeline. The infamous Delta Quadrant plays an important role. The ill-fated captain Clark Terrell from The Wrath of Khan makes his first appearance. But the most fascinating thing about Kirk being assigned to a new ship are the new crewmembers, particularly a Romulan first mate and a Tellarite doctor. This keeps the story from being another familiar retread.

By the end of this issue, all the members of the band, minus a Montgomery Scott still schooling wet-nosed cadets at Starfleet Academy, have been more or less reunited by an obligatory new threat to the Federation. “New” here being a relative term, because it’s actually an all-too familiar enemy in the original timeline. In fact, I’m surprised that such a significant adversary was introduced so early in the series and in a comic book instead of being reserved for a future film.

Star Trek: Waypoint #1

Story: Donny Cates, Sandra Lanz

Art: Mack Chater, Sandra Lanz

Colors: Jason Lewis, Dee Cunniffe

Letters: AndWorld Designs

If the Kelvin timeline isn’t making the jump to the small screen anytime soon, the original timeline is still being treated as fertile ground for now. A new television series is currently in the late stages of development and will be released next year. In the meantime, IDW’s new anthology series Star Trek: Waypoint is the venue for creators to tell stories in the vein of classic Star Trek. Using well-trod characters who already embody the humanitarian spirit approved by the late Gene Roddenberry. These are stories that would fit into the episodic structure of a typical Trek series. They’re light on extravagant action set-pieces, but composed largely of intimate conversations characteristic of the franchise. Waypoint offers a taste for what Trek was to many fans.

Occupying the bulk of the issue, “Puzzles” features an out of continuity tale about an Enterprise run by two people: Geordi La Forge and Data. Geordi has been promoted to ship’s captain while Data’s mind has been uploaded into the Enterprise mainframe. Data now projects holograms of himself while working on every task on the bridge, and even in other parts of the ship. Needless to say, it’s an eerie sight to see Geordi surrounded by only one other ghostlike presence.

When the Enterprise encounters an immense glowing cube floating in deep space, their attempts to make contact are rebuffed. But they soon figure out that the cube is a time-displaced vessel that is critically damaged, putting its own crew in mortal danger. However, Geordi and Data soon discover that rescuing the crew might possibly be breaking the Prime Directive.

This type of moral quandary is par for the course for The Next Generation, and so is the eventual solution which favors compassion over a strictly legalistic interpretation of the law. Geordi and Data, who usually operate as the braintrust for captain Jean-Luc Picard, now behave more like a Kirk and Spock when pondering their actions. Data even paraphrases Spock’s famous dictum “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” Artist Mack Chater isn’t the most evocative when trying to portray Trek’s futuristic setting, but he gets to draw these two as older, more world-weary individuals making difficult choices.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

It occurred to me that I haven’t discussed any of the comic books being published to honor the occasion of Star Trek’s 50th anniversary. So here are two titles from IDW. I’ve found the marketing surrounding this milestone to be strangely anemic, and I wasn’t aware of these comics until the last few days. How pitiful is that?

Star Trek: Boldly Go #1

Story: Mike Johnson

Art: Tony Shasteen

Colors: Davide Mastrolonardo

Letters: AndWorld Designs