In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

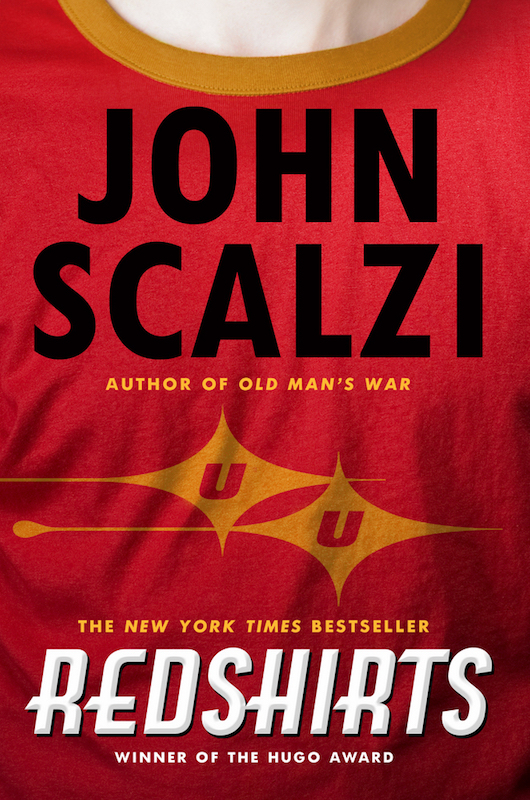

Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas

By John Scalzi

One inescapable part of being a 21st century consumer of popular genre entertainment is the impossibility of ignoring any discussion about the multitude of tropes it generates. Televised science fiction is no exception in this regard. And Star Trek is often credited with inventing, or at the very least popularizing, many sci-fi tropes. As I pointed out in my look at The Physics of Star Trek, the venerable franchise has already generated a considerable amount of discussion from fans possessing differing academic credentials. But the most accessible way to examine the unreality of fiction is through the use of metafictional devices. Irony and self-reflection are the order of the day, especially when dealing with works that are already decades old. What’s the point anymore in denying that one isn’t watching or reading a work of fiction? Named after one of Trek’s most well known conventions, Redshirts begins very much the way most fans would probably expect. But in order to fill over 300 pages, author John Scalzi pushes the conceit to its logical extreme.

That conceit was already touched on in the 1999 comedy Galaxy Quest. In the film, the cast of an old sci-fi show are made to reprise their roles for the benefit of a group of naive aliens who've confused the show for footage of real events. As a result actor Guy Fleegman (played by Sam Rockwell) is filled with fear that he will die at any moment because his role on the show was a redshirt - a random crewmember who looses his life in one episode. Guy’s terror mounts with every dangerous situation they face until he’s eventually convinced by one of the cast regulars that he could be instead playing the plucky comic relief. He undergoes a quick personal transformation, especially after someone else dies dramatically in his place.

In the novel, a group of ensigns working for the intergalactic organization named the Universal Union (affectionately called the Dub U) have just been assigned to the starship Intrepid. The ensigns treat this like any other assignment until they all realize they’re replacing dead crewmembers. In fact, the Intrepid has a notoriously high turnover rate because crewmembers keep getting killed on every away mission. Even odder, every mission is composed of at least one bridge officer. While they might occasionally endure bodily injury, they’re apparently immune to death. The bridge officers are entirely oblivious to this oddity even when it's pointed out to them. But the rest of the crew lives in a state of constant terror, just like Guy. They make themselves scarce whenever one of the officers are nearby. And they’ve developed a bizarre set of superstitious behaviors designed to minimize the body count, based on which officer they’re accompanying on a mission.

If this was the full extent of the novel, it would be nothing more than a clever parody of a famous television show. But these redshirts refuse to be just glorified extras, they want to be the heroes of their own story. So they make a point of getting to the root cause of this enigma. And without giving away too much, they’re eventually confronted with the absurdly fictional nature of their own existence. Scalzi's redshirts are actually competent scientists, which makes their observations about the universe they live in all the more painfully ironic.

This draws attention to the paradox of Star Trek's appeal. Like many science fiction authors, Scalzi is pretty critical about how science is often portrayed on televised sci-fi. It’s rules are often inconsistent and continuosly altered to serve the narrative. The redshirts often give voice this analysis. A bridge officer who’s an obvious analog for Pavel Chekov is exposed to a life threatening disease, but is saved at the last moment by a literal magic box. He’s horribly mangled by killer robots, only to fully recover a few days later. When the redshirts debate about a possible method for time travel, they note that the only reason it could possibly work is if the procedure included one of the bridge officers. And they’re completely mystified by the sheer number of nonsensical deaths suffered by the Intrepid’s crewmembers: Longranian ice sharks, Borgovian land worms, Pornathic crabs. Weirdness piled upon weirdness.

Star Trek’s fanciful vision of space exploration looks more anachronistic today than it would have back in the 1960s. And yet the franchise is often cited as an inspiration that made actual space exploration a reality. The science might be iffy, but its optimistic view of the future proved to be enduring. Even Scalzi’s critique is made from a position of affection for the television show. His protagonists have an unfortunate tendency towards quippishness, but they’re an intelligent and mostly sympathetic bunch who work together just as well as any Starfleet crew. Enough so that when one of them dies, the demise comes across as wasteful.

Redshirts runs out of plot before the book ends. The last third of the book is a lengthy meditation on the nature of fiction and its connection to reality, written as 3 lengthy codas. Scalzi explores the intimate relationship between writers and their creations. The fear writers have that the characters they hurt and kill on the page are truly suffering somewhere out there is thematically similar to the 2006 film Stranger than Fiction. The codas are tonally dissonant and focus on a completely different set of characters, so that it’s best to think of them not as the conclusion to the main story, but as a separate, if related, body of work. Unnecessary perhaps, but one that rounds out Scalzi’s own metafictional examination. Overall, he took kind of an awfully crazy journey to get there.