Go to: The Nib, by Kasia Babis

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

12/22/2017

12/08/2017

Cartoon: There’s a Consensus on Climate Change. Time To Take It Seriously

Go to: The Nib, by Caitlin Cass

4/09/2017

Arrival (2016)

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Starring: Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner and Forest Whitaker

Based on "Story of Your Life" by Ted Chiang

Hollywood portrayals of first contact with alien life can range from the mostly benevolent (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Contact) to the mostly world-threatening (War of the Worlds, Independence Day). Sometimes the aliens stand in judgement over humanity (The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Abyss). Or maybe the material circumstances are a lot more petty (Alien, Predator, Fire in the Sky) or desperate (E.T., District 9, Paul). But how many of them posit that an encounter with beings from an alien civilization will be mostly frustrating to us? In most of these films, the aliens possess fairly recognizable motives and behaviors, and sometimes even bear a familiar humanoid appearance. Arrival however begins with the premise that when the aliens do show up at our doorstep, their motives will be opaque to us. And without a universal translator available, we’ll be spending an inordinate amount of time figuring out their language before we can ask the question “What is your purpose on Earth?”

This is what linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) has to patiently explain to the less than pleased U.S. Army Colonel G.T. Weber (Forest Whitaker), a man under enormous pressure to come up with quick answers when 12 lens-shaped spacecraft appear out of nowhere and hover over 12 different locations across the globe. The squid-like aliens have hollowed out a large chamber within each spacecraft where they pump in enough air to allow humans to survive for two hours at a time. The humans can then personally interact with the aliens through a transparent partition. But none of the scientists sent in to communicate with them can make heads or tails of their strange vocalizations, until Weber sends Banks to the spacecraft hovering over rural Montana to decipher the “Heptapod” language.

And even when Banks makes enough headway to start asking the blunt questions her bosses demand, the answers she gets are maddeningly confusing. Meanings found in the words from any human language are often ambiguous enough, let alone the strange writings originating from an extraterrestrial society. Are the Heptapods offering the humans an ultimate weapon, advanced star drive technology, or are they simply sharing information? Are they trying to set the U.S. and China against each other? Every possible nuance in the translation keeps sending the world’s governments closer to the brink of a third world war.

I won’t spoil the big plot twist, which involves a very fanciful extrapolation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. But the film’s theme of how language can determine our experience of reality is handled with very subtle pacing that ties Banks’ personal life with the larger international crisis. Attempts to coordinate the separate translation efforts of the Heptapod language divides the world and exacerbates cultural misunderstandings like some otherworldly Tower of Babel. But as Banks begins to dream in Heptapod, she experiences visions that seem to collapse her perception of time. Earlier flashbacks of her life which seem completely irrelevant to the main story start to congeal into a pattern that mirrors the Heptapod’s swirling ideograms.

Arrival’s third act revelation shares a few parallels to Interstellar, though the 2014 film’s attempt to mesh relativistic physics with the Power of Love comes across as trite. Arrival’s own reveal isn’t anymore scientifically plausible, but the film’s tighter focus on Banks yields far more convincing results. Shifting the attention towards linguists instead of the usual collection of scientists and mathematicians lends a fresh perspective. Everything takes on greater importance when the fate of two species is dependent on comprehending the other side’s motivations.

But the film’s greatest asset is Adams, as the story could have collapsed under the weight of its own ideas if not for her highly calibrated performance. Adams makes excellent use of her own sweet, unthreatening demeanour to convey a character who’s understandably overwhelmed by the momentous nature of the occasion, but hiding a steely resolve that slowly emerges as the stakes are raised. During their first meeting, theoretical physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner) quickly dismisses Banks expertise, and by extension the contributions of the entire field of linguistics, as secondary to his own field. But when set next to Adam’s understated brilliance, Renner’s cocksure pose ends up looking brittle and amusingly childish. From that point there’s never any doubt about who becomes the leading voice in understanding the Heptapods, or her own species.

Starring: Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner and Forest Whitaker

Based on "Story of Your Life" by Ted Chiang

Hollywood portrayals of first contact with alien life can range from the mostly benevolent (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Contact) to the mostly world-threatening (War of the Worlds, Independence Day). Sometimes the aliens stand in judgement over humanity (The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Abyss). Or maybe the material circumstances are a lot more petty (Alien, Predator, Fire in the Sky) or desperate (E.T., District 9, Paul). But how many of them posit that an encounter with beings from an alien civilization will be mostly frustrating to us? In most of these films, the aliens possess fairly recognizable motives and behaviors, and sometimes even bear a familiar humanoid appearance. Arrival however begins with the premise that when the aliens do show up at our doorstep, their motives will be opaque to us. And without a universal translator available, we’ll be spending an inordinate amount of time figuring out their language before we can ask the question “What is your purpose on Earth?”

This is what linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) has to patiently explain to the less than pleased U.S. Army Colonel G.T. Weber (Forest Whitaker), a man under enormous pressure to come up with quick answers when 12 lens-shaped spacecraft appear out of nowhere and hover over 12 different locations across the globe. The squid-like aliens have hollowed out a large chamber within each spacecraft where they pump in enough air to allow humans to survive for two hours at a time. The humans can then personally interact with the aliens through a transparent partition. But none of the scientists sent in to communicate with them can make heads or tails of their strange vocalizations, until Weber sends Banks to the spacecraft hovering over rural Montana to decipher the “Heptapod” language.

And even when Banks makes enough headway to start asking the blunt questions her bosses demand, the answers she gets are maddeningly confusing. Meanings found in the words from any human language are often ambiguous enough, let alone the strange writings originating from an extraterrestrial society. Are the Heptapods offering the humans an ultimate weapon, advanced star drive technology, or are they simply sharing information? Are they trying to set the U.S. and China against each other? Every possible nuance in the translation keeps sending the world’s governments closer to the brink of a third world war.

I won’t spoil the big plot twist, which involves a very fanciful extrapolation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. But the film’s theme of how language can determine our experience of reality is handled with very subtle pacing that ties Banks’ personal life with the larger international crisis. Attempts to coordinate the separate translation efforts of the Heptapod language divides the world and exacerbates cultural misunderstandings like some otherworldly Tower of Babel. But as Banks begins to dream in Heptapod, she experiences visions that seem to collapse her perception of time. Earlier flashbacks of her life which seem completely irrelevant to the main story start to congeal into a pattern that mirrors the Heptapod’s swirling ideograms.

Arrival’s third act revelation shares a few parallels to Interstellar, though the 2014 film’s attempt to mesh relativistic physics with the Power of Love comes across as trite. Arrival’s own reveal isn’t anymore scientifically plausible, but the film’s tighter focus on Banks yields far more convincing results. Shifting the attention towards linguists instead of the usual collection of scientists and mathematicians lends a fresh perspective. Everything takes on greater importance when the fate of two species is dependent on comprehending the other side’s motivations.

But the film’s greatest asset is Adams, as the story could have collapsed under the weight of its own ideas if not for her highly calibrated performance. Adams makes excellent use of her own sweet, unthreatening demeanour to convey a character who’s understandably overwhelmed by the momentous nature of the occasion, but hiding a steely resolve that slowly emerges as the stakes are raised. During their first meeting, theoretical physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner) quickly dismisses Banks expertise, and by extension the contributions of the entire field of linguistics, as secondary to his own field. But when set next to Adam’s understated brilliance, Renner’s cocksure pose ends up looking brittle and amusingly childish. From that point there’s never any doubt about who becomes the leading voice in understanding the Heptapods, or her own species.

2/08/2017

1/16/2017

The Unstoppable Wasp #1

Story: Jeremy Whitley

Art: Elsa Charretier

Covers: Nicolas Bannister, Elizabeth Torque, Nelson Blake II, Guru eFX, Skottie Young, John Tyler Christopher, Andy Park

Colors: Megan Wilson

Letters: Joe Caramagna

Nadia Pym created by Mark Waid and Alan Davis.

Henry Pym has left the Marvel Universe a problematic legacy of homicidal robots, multiple identities, and generally terrible behavior. So it falls to his newly revealed, long-lost daughter Nadia to make superhero science fun again. The latest legacy character being utilized to add some much needed diversity to the Marvel lineup, her own title The Unstoppable Wasp is being written by Princeless creator Jeremy Whitley. The result is probably the most forthright statement yet from Marvel about the necessity for women to enter and lead the S.T.E.M. fields.

Nadia is a very different person from Henry or his socialite spouse Janet, the original bearer of the Wasp identity. She’s inherited her dad’s gift for science, but was hidden from him and raised by the same evil organization which moulded Natasha Romanova into the super spy Black Widow. Nadia escaped to America after successfully replicating Henry's shrinking technology and took up the mantle of the Wasp. Rather than growing into the typical brooding adolescent Marvel superhero, she embraces her newfound freedom with all the optimism of youth. Ready to discover the experiences she missed out on when she was still chained to her lab. Nadia is irrepressible. And her first important step: deciding what balushahi to pick out from the dessert counter.

The comic’s set piece is a downtown battle against a giant robot with the help of Kamala Khan and Bobbi Morse/Mockingbird, an antagonist drawn by Elsa Charretier like the clunky automatons superheroes are usually running into. But the fight is portrayed as a fun diversion in which Nadia gets to showcase her talents by hacking the robot and making it dance ballet. Nadia has a running inner monologue where she analyzes the robot’s joints for weaknesses which can be a little ungainly. But Whitley and Charretier are definitely having a ball with Nadia as she decides to science the s@*& out of this thing.

However, the heart of the story is revealed afterward in a conversation between Bobbi and Nadia. It’s a rare reminder that before Bobbi became a superhero, she actually started out as "Dr. Barbara Morse," a scientist. Bobbi mentions the S.H.I.E.L.D. list of the world’s smartest people, which has been dominated by men for decades until only very recently when Moon Girl shot right to the top.”There’s no way that’s right.” she intones about the paucity of females, and Nadia concurs. The meta commentary is further reinforced in a closing section profiling two real world scientists. Women scientists have always been here, they’ve just been ignored for so long. It’s now Nadia’s mission to point them out.

Art: Elsa Charretier

Covers: Nicolas Bannister, Elizabeth Torque, Nelson Blake II, Guru eFX, Skottie Young, John Tyler Christopher, Andy Park

Colors: Megan Wilson

Letters: Joe Caramagna

Nadia Pym created by Mark Waid and Alan Davis.

Henry Pym has left the Marvel Universe a problematic legacy of homicidal robots, multiple identities, and generally terrible behavior. So it falls to his newly revealed, long-lost daughter Nadia to make superhero science fun again. The latest legacy character being utilized to add some much needed diversity to the Marvel lineup, her own title The Unstoppable Wasp is being written by Princeless creator Jeremy Whitley. The result is probably the most forthright statement yet from Marvel about the necessity for women to enter and lead the S.T.E.M. fields.

Nadia is a very different person from Henry or his socialite spouse Janet, the original bearer of the Wasp identity. She’s inherited her dad’s gift for science, but was hidden from him and raised by the same evil organization which moulded Natasha Romanova into the super spy Black Widow. Nadia escaped to America after successfully replicating Henry's shrinking technology and took up the mantle of the Wasp. Rather than growing into the typical brooding adolescent Marvel superhero, she embraces her newfound freedom with all the optimism of youth. Ready to discover the experiences she missed out on when she was still chained to her lab. Nadia is irrepressible. And her first important step: deciding what balushahi to pick out from the dessert counter.

The comic’s set piece is a downtown battle against a giant robot with the help of Kamala Khan and Bobbi Morse/Mockingbird, an antagonist drawn by Elsa Charretier like the clunky automatons superheroes are usually running into. But the fight is portrayed as a fun diversion in which Nadia gets to showcase her talents by hacking the robot and making it dance ballet. Nadia has a running inner monologue where she analyzes the robot’s joints for weaknesses which can be a little ungainly. But Whitley and Charretier are definitely having a ball with Nadia as she decides to science the s@*& out of this thing.

However, the heart of the story is revealed afterward in a conversation between Bobbi and Nadia. It’s a rare reminder that before Bobbi became a superhero, she actually started out as "Dr. Barbara Morse," a scientist. Bobbi mentions the S.H.I.E.L.D. list of the world’s smartest people, which has been dominated by men for decades until only very recently when Moon Girl shot right to the top.”There’s no way that’s right.” she intones about the paucity of females, and Nadia concurs. The meta commentary is further reinforced in a closing section profiling two real world scientists. Women scientists have always been here, they’ve just been ignored for so long. It’s now Nadia’s mission to point them out.

11/27/2016

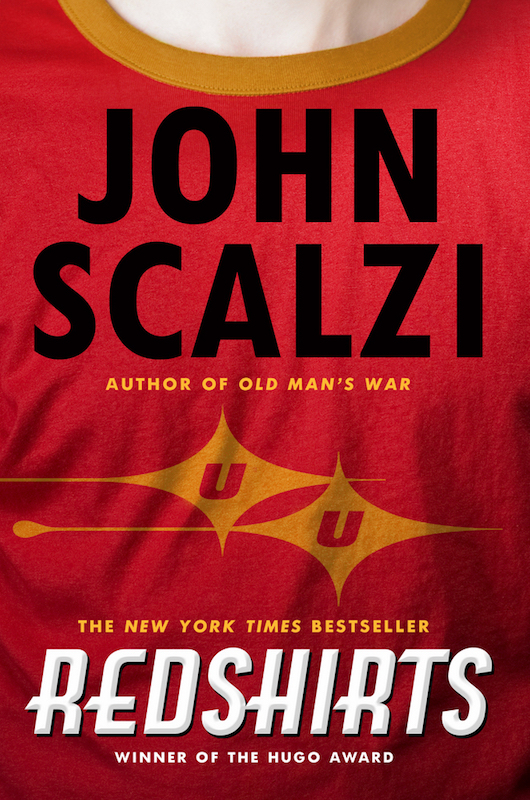

50th Trek: Redshirts

In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas

By John Scalzi

One inescapable part of being a 21st century consumer of popular genre entertainment is the impossibility of ignoring any discussion about the multitude of tropes it generates. Televised science fiction is no exception in this regard. And Star Trek is often credited with inventing, or at the very least popularizing, many sci-fi tropes. As I pointed out in my look at The Physics of Star Trek, the venerable franchise has already generated a considerable amount of discussion from fans possessing differing academic credentials. But the most accessible way to examine the unreality of fiction is through the use of metafictional devices. Irony and self-reflection are the order of the day, especially when dealing with works that are already decades old. What’s the point anymore in denying that one isn’t watching or reading a work of fiction? Named after one of Trek’s most well known conventions, Redshirts begins very much the way most fans would probably expect. But in order to fill over 300 pages, author John Scalzi pushes the conceit to its logical extreme.

That conceit was already touched on in the 1999 comedy Galaxy Quest. In the film, the cast of an old sci-fi show are made to reprise their roles for the benefit of a group of naive aliens who've confused the show for footage of real events. As a result actor Guy Fleegman (played by Sam Rockwell) is filled with fear that he will die at any moment because his role on the show was a redshirt - a random crewmember who looses his life in one episode. Guy’s terror mounts with every dangerous situation they face until he’s eventually convinced by one of the cast regulars that he could be instead playing the plucky comic relief. He undergoes a quick personal transformation, especially after someone else dies dramatically in his place.

In the novel, a group of ensigns working for the intergalactic organization named the Universal Union (affectionately called the Dub U) have just been assigned to the starship Intrepid. The ensigns treat this like any other assignment until they all realize they’re replacing dead crewmembers. In fact, the Intrepid has a notoriously high turnover rate because crewmembers keep getting killed on every away mission. Even odder, every mission is composed of at least one bridge officer. While they might occasionally endure bodily injury, they’re apparently immune to death. The bridge officers are entirely oblivious to this oddity even when it's pointed out to them. But the rest of the crew lives in a state of constant terror, just like Guy. They make themselves scarce whenever one of the officers are nearby. And they’ve developed a bizarre set of superstitious behaviors designed to minimize the body count, based on which officer they’re accompanying on a mission.

If this was the full extent of the novel, it would be nothing more than a clever parody of a famous television show. But these redshirts refuse to be just glorified extras, they want to be the heroes of their own story. So they make a point of getting to the root cause of this enigma. And without giving away too much, they’re eventually confronted with the absurdly fictional nature of their own existence. Scalzi's redshirts are actually competent scientists, which makes their observations about the universe they live in all the more painfully ironic.

This draws attention to the paradox of Star Trek's appeal. Like many science fiction authors, Scalzi is pretty critical about how science is often portrayed on televised sci-fi. It’s rules are often inconsistent and continuosly altered to serve the narrative. The redshirts often give voice this analysis. A bridge officer who’s an obvious analog for Pavel Chekov is exposed to a life threatening disease, but is saved at the last moment by a literal magic box. He’s horribly mangled by killer robots, only to fully recover a few days later. When the redshirts debate about a possible method for time travel, they note that the only reason it could possibly work is if the procedure included one of the bridge officers. And they’re completely mystified by the sheer number of nonsensical deaths suffered by the Intrepid’s crewmembers: Longranian ice sharks, Borgovian land worms, Pornathic crabs. Weirdness piled upon weirdness.

Star Trek’s fanciful vision of space exploration looks more anachronistic today than it would have back in the 1960s. And yet the franchise is often cited as an inspiration that made actual space exploration a reality. The science might be iffy, but its optimistic view of the future proved to be enduring. Even Scalzi’s critique is made from a position of affection for the television show. His protagonists have an unfortunate tendency towards quippishness, but they’re an intelligent and mostly sympathetic bunch who work together just as well as any Starfleet crew. Enough so that when one of them dies, the demise comes across as wasteful.

Redshirts runs out of plot before the book ends. The last third of the book is a lengthy meditation on the nature of fiction and its connection to reality, written as 3 lengthy codas. Scalzi explores the intimate relationship between writers and their creations. The fear writers have that the characters they hurt and kill on the page are truly suffering somewhere out there is thematically similar to the 2006 film Stranger than Fiction. The codas are tonally dissonant and focus on a completely different set of characters, so that it’s best to think of them not as the conclusion to the main story, but as a separate, if related, body of work. Unnecessary perhaps, but one that rounds out Scalzi’s own metafictional examination. Overall, he took kind of an awfully crazy journey to get there.

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas

By John Scalzi

One inescapable part of being a 21st century consumer of popular genre entertainment is the impossibility of ignoring any discussion about the multitude of tropes it generates. Televised science fiction is no exception in this regard. And Star Trek is often credited with inventing, or at the very least popularizing, many sci-fi tropes. As I pointed out in my look at The Physics of Star Trek, the venerable franchise has already generated a considerable amount of discussion from fans possessing differing academic credentials. But the most accessible way to examine the unreality of fiction is through the use of metafictional devices. Irony and self-reflection are the order of the day, especially when dealing with works that are already decades old. What’s the point anymore in denying that one isn’t watching or reading a work of fiction? Named after one of Trek’s most well known conventions, Redshirts begins very much the way most fans would probably expect. But in order to fill over 300 pages, author John Scalzi pushes the conceit to its logical extreme.

That conceit was already touched on in the 1999 comedy Galaxy Quest. In the film, the cast of an old sci-fi show are made to reprise their roles for the benefit of a group of naive aliens who've confused the show for footage of real events. As a result actor Guy Fleegman (played by Sam Rockwell) is filled with fear that he will die at any moment because his role on the show was a redshirt - a random crewmember who looses his life in one episode. Guy’s terror mounts with every dangerous situation they face until he’s eventually convinced by one of the cast regulars that he could be instead playing the plucky comic relief. He undergoes a quick personal transformation, especially after someone else dies dramatically in his place.

In the novel, a group of ensigns working for the intergalactic organization named the Universal Union (affectionately called the Dub U) have just been assigned to the starship Intrepid. The ensigns treat this like any other assignment until they all realize they’re replacing dead crewmembers. In fact, the Intrepid has a notoriously high turnover rate because crewmembers keep getting killed on every away mission. Even odder, every mission is composed of at least one bridge officer. While they might occasionally endure bodily injury, they’re apparently immune to death. The bridge officers are entirely oblivious to this oddity even when it's pointed out to them. But the rest of the crew lives in a state of constant terror, just like Guy. They make themselves scarce whenever one of the officers are nearby. And they’ve developed a bizarre set of superstitious behaviors designed to minimize the body count, based on which officer they’re accompanying on a mission.

If this was the full extent of the novel, it would be nothing more than a clever parody of a famous television show. But these redshirts refuse to be just glorified extras, they want to be the heroes of their own story. So they make a point of getting to the root cause of this enigma. And without giving away too much, they’re eventually confronted with the absurdly fictional nature of their own existence. Scalzi's redshirts are actually competent scientists, which makes their observations about the universe they live in all the more painfully ironic.

This draws attention to the paradox of Star Trek's appeal. Like many science fiction authors, Scalzi is pretty critical about how science is often portrayed on televised sci-fi. It’s rules are often inconsistent and continuosly altered to serve the narrative. The redshirts often give voice this analysis. A bridge officer who’s an obvious analog for Pavel Chekov is exposed to a life threatening disease, but is saved at the last moment by a literal magic box. He’s horribly mangled by killer robots, only to fully recover a few days later. When the redshirts debate about a possible method for time travel, they note that the only reason it could possibly work is if the procedure included one of the bridge officers. And they’re completely mystified by the sheer number of nonsensical deaths suffered by the Intrepid’s crewmembers: Longranian ice sharks, Borgovian land worms, Pornathic crabs. Weirdness piled upon weirdness.

Star Trek’s fanciful vision of space exploration looks more anachronistic today than it would have back in the 1960s. And yet the franchise is often cited as an inspiration that made actual space exploration a reality. The science might be iffy, but its optimistic view of the future proved to be enduring. Even Scalzi’s critique is made from a position of affection for the television show. His protagonists have an unfortunate tendency towards quippishness, but they’re an intelligent and mostly sympathetic bunch who work together just as well as any Starfleet crew. Enough so that when one of them dies, the demise comes across as wasteful.

Redshirts runs out of plot before the book ends. The last third of the book is a lengthy meditation on the nature of fiction and its connection to reality, written as 3 lengthy codas. Scalzi explores the intimate relationship between writers and their creations. The fear writers have that the characters they hurt and kill on the page are truly suffering somewhere out there is thematically similar to the 2006 film Stranger than Fiction. The codas are tonally dissonant and focus on a completely different set of characters, so that it’s best to think of them not as the conclusion to the main story, but as a separate, if related, body of work. Unnecessary perhaps, but one that rounds out Scalzi’s own metafictional examination. Overall, he took kind of an awfully crazy journey to get there.

Labels:

Commentary,

fantasy,

Prose,

science,

Star Trek,

television

11/08/2016

Map: AuthaGraph World Map

Go to: Good Design Award, by Hajime Narukawa (via William Turton)

9/24/2016

50th Trek: The Physics of Star Trek

In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

The Physics of Star Trek

by Lawrence M. Krauss

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

If Trekkies helped spawn the current fashion for fan-themed documentaries, The Physics of Star Trek would inspire the trend of books which blended two kinds of stereotypical nerdery - academia and pop culture. Virtually every successful franchise seems to have been subject to this kind of treatment: comic book superheroes and supervillains, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Harry Potter, even that other, less rational sci-fi series with “Star” in its title. Compared to the era when Carl Sagan or David Attenborough or Fritjof Capra would rarely deign to reference popular entertainment, our current big-brained public figures promoting education such as Michio Kaku or Phil Plait are more likely to mention the latest film, television show, or graphic novel, if it will help them make a point about how science functions in the real world. If author Lawrence Krauss may have initially treated the idea of a science book based on Star Trek a joke, it almost makes sense in retrospect as the logical start for the trend. When the book was published in 1995, Trek had already been talking about the future for almost 30 years.

The title for the book is somewhat misleading. The first half does cover the history of modern physics in more-or-less chronological order, from the classical mechanics of Isaac Newton, the two theories of relativity by Albert Einstein, atomic theory, to the weirdness that is quantum mechanics. But this is Star Trek after all, so Krauss must venture into the fields of astronomy and cosmology in later chapters. He even gives his two cents about biology, psychology, computer science, and philosophy, because of course he does. Unsurprisingly, it’s that last part where Krauss is at his least sure footed. At barely 175 pages, TPOST is a slim volume. But it’s hardly a quick read because of the nature of its subject matter. Nevertheless, Krauss does his best to cut down on the jargon, and there’s not a single mathematical equation in sight. The most he does to illuminate some of the more complex ideas being discussed is to use several schematic drawings. It’s about as plain-spoken as a physics-based science book written by a Ph.D. can get.

What does become apparent as the book progresses is the enormous difficulty of the task Krauss has set up for himself. Star Trek was already a massive franchise in 1995, which included The Original Series, The Next Generation, seven feature films, the first two seasons of Deep Space Nine, and the first season of Voyager. Given that TNG was the most successful part of the franchise, the book tends to reference it more than any of the other Trek series. Like a later-day positivist version of Capra, or a real world Sheldon Cooper, Krauss has to demonstrate fluency in two different realms, then attempt to draw a connection between them as both a trusted expert in his field, and as a judgemental fan.*

That’s not so simple because like any form of speculative fantasy, Star Trek isn’t just cribbing from the textbook. There’s a lot of artistic license involved in the writing of any episode. Trying to make sense of Trek’s fictional universe is like translating a book from English to Chinese, then into Korean, then French, then back into English. Basically, Krauss is assembling his own head-canon. When examining technologies such as the matter transporter or the holodeck, Krauss has to surmise from multiple episodes which aren’t always consistent with each other just how those technologies function before he can give an explanation on whether they might even be feasible in this universe. Is the matter transporter just transmitting a data-rich signal to the receiving device, or is it sending with it a matter stream as well? Is the holodeck just producing holograms, or is it also manipulating solid matter whenever necessary? When he synthesizes a model for how the warp drive might work, Krauss rather optimistically explains, “This scenario must be what the Star Trek writers intended when they invented warp drive, even if it bears little resemblance to the technical descriptions they have provided.” You don’t say?

As for the answers Krauss provides for Star Trek’s three key technologies (warp drive, time travel, matter transporter), here’s the (spoiler alert!) Cliff Notes version of his analysis. All of these technologies would generate stupendous energy requirements that make them virtually unfeasible. And while general relativity does make warp drive and travel to the past at least theoretically possible if not practical, matter transporters run into the theoretical limits of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which puts an absolute limit on the precision for measuring the fundamental properties of a subatomic particle. So no one’s beaming up any time soon.

Science has naturally moved on since 1995, though so far not in a direction that would change any of Krauss’ basic answers. The development of quantum teleportation uses particles for encoding and transmitting information, but still won’t allow us to transport a living person. Newer measurements about the fate of the Universe have led cosmologists to speculate about dark energy. The long hypothesized Higgs Boson particle was found in 2013. Another hypothesized phenomena, gravitational waves, was finally detected earlier this year. The discovery of thousands of exoplanets has only deepened the mystery of why we have not yet found new life and new civilization outside of the Earth. Even our own solar system has gotten so complicated that astronomers reclassified Pluto as a “dwarf planet”, whatever the hell that means. And as for exploring strange new worlds, NASA now faces competition from the private sector. But these companies arguably wouldn't exist in the first place without Stat Trek serving as inspiration.

However cleverly organized, TPOST utilizes only a very narrow set of tools to study the franchise. So it comes as no great shock that the book has galvanized other experts to give their own interpretations based on their particular field of knowledge. To date, this has included biology, computer science, ethics, business management, history, metaphysics, and religious studies. But I suspect that the book which will resonate most with the current market is the one that tackles how the Federation managed to build a post-scarcity society from a post-apocalyptic setting. If Lawrence Krauss has succeeded, however accidentally, in proving one thing, it’s that Star Trek can be viewed to be just about anything.

____

*Krauss prefers the label "Trekker" when talking about Star Trek fans.

The Physics of Star Trek

by Lawrence M. Krauss

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

If Trekkies helped spawn the current fashion for fan-themed documentaries, The Physics of Star Trek would inspire the trend of books which blended two kinds of stereotypical nerdery - academia and pop culture. Virtually every successful franchise seems to have been subject to this kind of treatment: comic book superheroes and supervillains, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Harry Potter, even that other, less rational sci-fi series with “Star” in its title. Compared to the era when Carl Sagan or David Attenborough or Fritjof Capra would rarely deign to reference popular entertainment, our current big-brained public figures promoting education such as Michio Kaku or Phil Plait are more likely to mention the latest film, television show, or graphic novel, if it will help them make a point about how science functions in the real world. If author Lawrence Krauss may have initially treated the idea of a science book based on Star Trek a joke, it almost makes sense in retrospect as the logical start for the trend. When the book was published in 1995, Trek had already been talking about the future for almost 30 years.

The title for the book is somewhat misleading. The first half does cover the history of modern physics in more-or-less chronological order, from the classical mechanics of Isaac Newton, the two theories of relativity by Albert Einstein, atomic theory, to the weirdness that is quantum mechanics. But this is Star Trek after all, so Krauss must venture into the fields of astronomy and cosmology in later chapters. He even gives his two cents about biology, psychology, computer science, and philosophy, because of course he does. Unsurprisingly, it’s that last part where Krauss is at his least sure footed. At barely 175 pages, TPOST is a slim volume. But it’s hardly a quick read because of the nature of its subject matter. Nevertheless, Krauss does his best to cut down on the jargon, and there’s not a single mathematical equation in sight. The most he does to illuminate some of the more complex ideas being discussed is to use several schematic drawings. It’s about as plain-spoken as a physics-based science book written by a Ph.D. can get.

What does become apparent as the book progresses is the enormous difficulty of the task Krauss has set up for himself. Star Trek was already a massive franchise in 1995, which included The Original Series, The Next Generation, seven feature films, the first two seasons of Deep Space Nine, and the first season of Voyager. Given that TNG was the most successful part of the franchise, the book tends to reference it more than any of the other Trek series. Like a later-day positivist version of Capra, or a real world Sheldon Cooper, Krauss has to demonstrate fluency in two different realms, then attempt to draw a connection between them as both a trusted expert in his field, and as a judgemental fan.*

That’s not so simple because like any form of speculative fantasy, Star Trek isn’t just cribbing from the textbook. There’s a lot of artistic license involved in the writing of any episode. Trying to make sense of Trek’s fictional universe is like translating a book from English to Chinese, then into Korean, then French, then back into English. Basically, Krauss is assembling his own head-canon. When examining technologies such as the matter transporter or the holodeck, Krauss has to surmise from multiple episodes which aren’t always consistent with each other just how those technologies function before he can give an explanation on whether they might even be feasible in this universe. Is the matter transporter just transmitting a data-rich signal to the receiving device, or is it sending with it a matter stream as well? Is the holodeck just producing holograms, or is it also manipulating solid matter whenever necessary? When he synthesizes a model for how the warp drive might work, Krauss rather optimistically explains, “This scenario must be what the Star Trek writers intended when they invented warp drive, even if it bears little resemblance to the technical descriptions they have provided.” You don’t say?

As for the answers Krauss provides for Star Trek’s three key technologies (warp drive, time travel, matter transporter), here’s the (spoiler alert!) Cliff Notes version of his analysis. All of these technologies would generate stupendous energy requirements that make them virtually unfeasible. And while general relativity does make warp drive and travel to the past at least theoretically possible if not practical, matter transporters run into the theoretical limits of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which puts an absolute limit on the precision for measuring the fundamental properties of a subatomic particle. So no one’s beaming up any time soon.

Science has naturally moved on since 1995, though so far not in a direction that would change any of Krauss’ basic answers. The development of quantum teleportation uses particles for encoding and transmitting information, but still won’t allow us to transport a living person. Newer measurements about the fate of the Universe have led cosmologists to speculate about dark energy. The long hypothesized Higgs Boson particle was found in 2013. Another hypothesized phenomena, gravitational waves, was finally detected earlier this year. The discovery of thousands of exoplanets has only deepened the mystery of why we have not yet found new life and new civilization outside of the Earth. Even our own solar system has gotten so complicated that astronomers reclassified Pluto as a “dwarf planet”, whatever the hell that means. And as for exploring strange new worlds, NASA now faces competition from the private sector. But these companies arguably wouldn't exist in the first place without Stat Trek serving as inspiration.

However cleverly organized, TPOST utilizes only a very narrow set of tools to study the franchise. So it comes as no great shock that the book has galvanized other experts to give their own interpretations based on their particular field of knowledge. To date, this has included biology, computer science, ethics, business management, history, metaphysics, and religious studies. But I suspect that the book which will resonate most with the current market is the one that tackles how the Federation managed to build a post-scarcity society from a post-apocalyptic setting. If Lawrence Krauss has succeeded, however accidentally, in proving one thing, it’s that Star Trek can be viewed to be just about anything.

____

*Krauss prefers the label "Trekker" when talking about Star Trek fans.

Labels:

Commentary,

fantasy,

film,

Prose,

science,

Star Trek,

television

9/17/2016

50th Trek: Trekkies (1997)

In honour of Star Trek's 50th anniversary, I'm writing a series of posts discussing a favorite example of Star Trek related media.

Trekkies (1997)

Director: Roger Nygard

Host: Denise Crosby

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

Trekkies quickly latches on to cosplay as a signifier of the more eccentric fan. Family man David Greenstein has a Star Trek-themed man cave and bathroom at home. To his wife’s horror, he admits to wanting to modify his earlobes in order to appear more Vulcan. Alas, he can’t afford the operation. Denis Bourguignon runs a sci-fi themed dental office, complete with staff wearing blue science officer uniforms. He and wife Shelly admit, to the embarrassment of the film’s host Denise Crosby (Tasha Yar from The Next Generation), that cosplay plays a significant part in their sex life. Richard Kronfeld is fascinated by Trek’s fictional technology. He’s seen motoring down a road to the local Radio Shack using a homebuilt replica of the Total Life Support Unit used by Captain Pike. But the most charming example is the teenager Gabriel Köerner, who would go on to become the film’s most recognised character after Adams. Always filmed in costume, Köerner is the kind of passionate, nerdy, self-aware kid who proves to be an eloquent spokesperson. He’s the one who when his interview is interrupted by an unexpected phone call, responds with the immortal line "Peter, this is the worst time you could have called! Go away! ... ok bye."

Naturally, the Klingons take things a step further. They write sex manuals and enact their mating rituals, learn the Klingon language, and translate everything from the Bible, William Shakespeare, popular theme songs, to sports terminology. Some of them even have time to be heavily involved with charitable work. Other fans are also inspired to follow different creative paths. Köerner proudly displays the CGI models he made for a fan film being produced by his club. Filk (science fiction folk singing) gets only a brief mention. As do several female fans who read and write “slash” fiction (erotic fan fiction), though Debbie Warner is singled out as a member of an anonymous mailing list and author of “The Secret Logs of Mistress Janeway.” This is juxtaposed with a scene of Crosby showing off her personal fan art collection, which includes several risqué illustrations of Tasha and Data (played by Brent Spiner in TNG) captured in flagrante delicto.

However, the true weirdos are only mentioned in passing. There’s the guy who wants to collect James Doohan’s (Montgomery “Scotty” Scott) blood. Another who paid $40-60 to drink the “Q-Virus.” Another who wanted Ethan Phillips (Neelix from Voyager) to help him ease his way into death. Or the guy who keeps sending brochures addressed to “Star Trek.”

It’s this fixed component of amused ogling that seems to have upset fans at the time. Still, it would be a huge mistake to think that Trekkies goes out of its way to mock its subject matter. The cast and crew being interviewed consistently express awe and admiration for Trek’s enduring popularity. A recurring motif is how Trek’s progressive message has inspired a lot of people, including women and minorities. And many of the actors (though William Shatner [James Kirk] is noticeably absent) can recall positive interactions with their fans, whether they were media personalities, NASA astronauts, or most notably, a suicidal woman who was gently coaxed by Doohan to turn her life around.

What’s become more obvious since is that Trekkies blend of carnival sideshow and joyous celebration is a product of a different era. While geek culture was becoming ascendent in the 90s, it was nowhere as ubiquitous as it is today. A throwaway line from Köerner and a fansite created by superfan Anne Murphy serve as a reminders that geeks were still in the early stages of colonising the World Wide Web in 1997. As such, the film is informed by the need to expound on the nature of fandom to non-fans. Some viewers will unfortunately see these people as stupid or hopelessly deluded. But there’s a certain underdog quality that shines through. Many of the interviewees come across as erudite and cognisant of their outsider status. For the most part, they seem happy to pursue a hobby the world doesn’t get. And In our highly polarised environment where Gamergate, the backlash against Miles Morales, and other stories that serve as a reminder that sexist and racist attitudes exist within fandom, the pro-science, inclusive world view expressed in Trekkies is almost salutary, if a little earnest at times. Or as Spiner puts it “I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone, Star Trek fan or not, who wasn’t peculiar…. We’re all peculiar.”

Another thing that stands out is the film’s focus on the convention as a defining characteristic of fandom. Apparently, not everyone knew back then what basically goes on during a convention. So Trekkies takes time to point out that people mingle with friends and other like-minded individuals, buy and sell a lot of merchandise, meet some of the personalities involved with the franchise, and take lots of pictures. When compared to the massive Hollywood presence seen in Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan's Hope, these conventions possess far humbler production values, and are more local in reach. Not that it stops anyone from spending thousands of dollars on, say, a genuine Klingon forehead prosthetic. But that sense of "I have found my tribe" is a constant. As one attendee speaking for herself and her friends recalls "The first convention we went to... we were all accepted. And when we left and went back home, we had to act normal again." Several Hollywood representations of fan conventions have since taken their cue from Trekkies.

While surveying a broad spectrum of modern fan pursuits, Trekkies is smart enough not to over-explain Star Trek itself. The film doesn’t go into any detail about Trek’s fictional universe, and only mentions a few of the people behind its creation. The references and technical jargon will be appreciated by the initiated. But the viewer isn’t punished for not knowing the meaning behind “The Emissary”, “saucer separation capability”, “Romulan Star Empire”, or for not caring about the never-ending debate over who is Trek’s favourite captain (thankfully, Captain Archer wasn’t in the running at the time).

One particular debate that actually hasn’t aged very well is whether fans should refer to themselves as Trekkies or Trekkers. The film’s participants express a range of opinions favouring one term over the other, but what underlies all their arguments is a wish for greater respectability. What all of them fail to recognise is how little control anyone has over the popular use of language. In an age where Internet memes are easily co-opted by an opposing side, the idea that a simple word change could alter the prevailing perception surrounding an entire subculture can feel a little naive. But then again, the same could be said of Star Trek.

Trekkies (1997)

Director: Roger Nygard

Host: Denise Crosby

Star Trek created by Gene Roddenberry.

“I don’t know, I hope it lasts forever … As long as it’s thoughtful, it’s a good thing."One of the early criticisms levelled at Trekkies from the very community it was portraying was that it spent way too much time parading a more extreme version of Star Trek fandom instead of representing the majority composed of more “normal” fans. The documentary’s most infamous character was and continues to be Barbara Adams, an alternate juror for the Whitewater trial of Governor Jim Guy Tucker who achieved nationwide notoriety for wearing her Starfleet uniform to the courtroom, tricorder, rank pips and all. When discussing her actions, she referred to her fellow fans, “I don’t want my officers to ever feel ashamed to wear their uniform.” On the face of it, it’s pretty ridiculous to compare a homemade costume to a military uniform. But she insisted on people showing respect for her rank of Lieutenant Commander, even at the printing press where she worked from within its binding and finishing department.

- Leonard Nimoy (1931-2015)

Trekkies quickly latches on to cosplay as a signifier of the more eccentric fan. Family man David Greenstein has a Star Trek-themed man cave and bathroom at home. To his wife’s horror, he admits to wanting to modify his earlobes in order to appear more Vulcan. Alas, he can’t afford the operation. Denis Bourguignon runs a sci-fi themed dental office, complete with staff wearing blue science officer uniforms. He and wife Shelly admit, to the embarrassment of the film’s host Denise Crosby (Tasha Yar from The Next Generation), that cosplay plays a significant part in their sex life. Richard Kronfeld is fascinated by Trek’s fictional technology. He’s seen motoring down a road to the local Radio Shack using a homebuilt replica of the Total Life Support Unit used by Captain Pike. But the most charming example is the teenager Gabriel Köerner, who would go on to become the film’s most recognised character after Adams. Always filmed in costume, Köerner is the kind of passionate, nerdy, self-aware kid who proves to be an eloquent spokesperson. He’s the one who when his interview is interrupted by an unexpected phone call, responds with the immortal line "Peter, this is the worst time you could have called! Go away! ... ok bye."

Naturally, the Klingons take things a step further. They write sex manuals and enact their mating rituals, learn the Klingon language, and translate everything from the Bible, William Shakespeare, popular theme songs, to sports terminology. Some of them even have time to be heavily involved with charitable work. Other fans are also inspired to follow different creative paths. Köerner proudly displays the CGI models he made for a fan film being produced by his club. Filk (science fiction folk singing) gets only a brief mention. As do several female fans who read and write “slash” fiction (erotic fan fiction), though Debbie Warner is singled out as a member of an anonymous mailing list and author of “The Secret Logs of Mistress Janeway.” This is juxtaposed with a scene of Crosby showing off her personal fan art collection, which includes several risqué illustrations of Tasha and Data (played by Brent Spiner in TNG) captured in flagrante delicto.

However, the true weirdos are only mentioned in passing. There’s the guy who wants to collect James Doohan’s (Montgomery “Scotty” Scott) blood. Another who paid $40-60 to drink the “Q-Virus.” Another who wanted Ethan Phillips (Neelix from Voyager) to help him ease his way into death. Or the guy who keeps sending brochures addressed to “Star Trek.”

It’s this fixed component of amused ogling that seems to have upset fans at the time. Still, it would be a huge mistake to think that Trekkies goes out of its way to mock its subject matter. The cast and crew being interviewed consistently express awe and admiration for Trek’s enduring popularity. A recurring motif is how Trek’s progressive message has inspired a lot of people, including women and minorities. And many of the actors (though William Shatner [James Kirk] is noticeably absent) can recall positive interactions with their fans, whether they were media personalities, NASA astronauts, or most notably, a suicidal woman who was gently coaxed by Doohan to turn her life around.

What’s become more obvious since is that Trekkies blend of carnival sideshow and joyous celebration is a product of a different era. While geek culture was becoming ascendent in the 90s, it was nowhere as ubiquitous as it is today. A throwaway line from Köerner and a fansite created by superfan Anne Murphy serve as a reminders that geeks were still in the early stages of colonising the World Wide Web in 1997. As such, the film is informed by the need to expound on the nature of fandom to non-fans. Some viewers will unfortunately see these people as stupid or hopelessly deluded. But there’s a certain underdog quality that shines through. Many of the interviewees come across as erudite and cognisant of their outsider status. For the most part, they seem happy to pursue a hobby the world doesn’t get. And In our highly polarised environment where Gamergate, the backlash against Miles Morales, and other stories that serve as a reminder that sexist and racist attitudes exist within fandom, the pro-science, inclusive world view expressed in Trekkies is almost salutary, if a little earnest at times. Or as Spiner puts it “I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone, Star Trek fan or not, who wasn’t peculiar…. We’re all peculiar.”

Another thing that stands out is the film’s focus on the convention as a defining characteristic of fandom. Apparently, not everyone knew back then what basically goes on during a convention. So Trekkies takes time to point out that people mingle with friends and other like-minded individuals, buy and sell a lot of merchandise, meet some of the personalities involved with the franchise, and take lots of pictures. When compared to the massive Hollywood presence seen in Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan's Hope, these conventions possess far humbler production values, and are more local in reach. Not that it stops anyone from spending thousands of dollars on, say, a genuine Klingon forehead prosthetic. But that sense of "I have found my tribe" is a constant. As one attendee speaking for herself and her friends recalls "The first convention we went to... we were all accepted. And when we left and went back home, we had to act normal again." Several Hollywood representations of fan conventions have since taken their cue from Trekkies.

While surveying a broad spectrum of modern fan pursuits, Trekkies is smart enough not to over-explain Star Trek itself. The film doesn’t go into any detail about Trek’s fictional universe, and only mentions a few of the people behind its creation. The references and technical jargon will be appreciated by the initiated. But the viewer isn’t punished for not knowing the meaning behind “The Emissary”, “saucer separation capability”, “Romulan Star Empire”, or for not caring about the never-ending debate over who is Trek’s favourite captain (thankfully, Captain Archer wasn’t in the running at the time).

One particular debate that actually hasn’t aged very well is whether fans should refer to themselves as Trekkies or Trekkers. The film’s participants express a range of opinions favouring one term over the other, but what underlies all their arguments is a wish for greater respectability. What all of them fail to recognise is how little control anyone has over the popular use of language. In an age where Internet memes are easily co-opted by an opposing side, the idea that a simple word change could alter the prevailing perception surrounding an entire subculture can feel a little naive. But then again, the same could be said of Star Trek.

9/13/2016

A Timeline of Earth's Average Temperature

Go to: xkcd, by Randall Munroe

9/07/2016

Video: Infinitude

Go to: Scott Portingale (via Jennifer Ouellette)

1/22/2016

8/12/2015

8/05/2015

6/13/2015

Noah

Story: Darren Aronofsky, Ari Handel

Art: Niko Henrichon

Letters: Nicolas Sénégas

Design: Tom Muller

The Biblical myth of the Flood is a dark tale about an all-powerful but petulant god who regrets creating humanity and decides to drown them all in a worldwide deluge. But he makes an exception for Noah and his family. Noah himself barely mutters a peep as he carries out God's commands without fail, like any trusted servant. God's act of universal destruction serves to complement the Genesis story of his creation of the world. But In Darren Aronofsky's retelling, God is absent. The psychodrama instead falls on Noah as he struggles to understand the deity's will, which he believes is being communicated to him through visions so cryptic they often leave him conflicted about their true meaning. His crisis of faith becomes the focal point in an ambitious story that attempts to weave ancient myth, medieval theology, and modern science into a heavy handed morality tale about human greed and environmental despoilation.

While the graphic novel functions as a standalone story, it's interesting to see how it compares to the film. Noah is humanity's first vegan/eco-terrorist/doomsday prepper, disapproving of civilization's wasteful practices and figuring out that the world is going to end. He's even more imposing in the comic, recognized by others as a great warrior and mage. Aronofsky and co-writer Ari Handel teamed-up with artist Niko Henrichon for the comic well before the film was produced, so it's visuals bear almost no resemblance to the film. Noah is drawn as a cape wearing, long-haired, square-jawed heroic type who wouldn't look out of place within a Robert E. Howard fantasy novel or a Thor comic. His appearance takes on a more sinister aspect down the line as he evolves into a full-blown religious zealot.

But the people Noah actually terrorizes are his own family, whom he's already sequestered from society when the story begins. God's reticence towards Noah in Genesis is translated in this humanistic adaptation as Noah's confusion as to whether God (dubbed the "Creator") intends for humanity to survive or go extinct. Like in the film, his increasing conviction that Original Sin has made them unworthy of the the former creates a rift with his family. And his behavior is far more extreme in the comic. At one point, he even sets the animals of the Ark against them when they defy him. This Noah takes no prisoners.

Henrichon's antediluvian setting is also visually striking. One of the underwhelming things about the film was its subdued palette suggesting a burnt out, featureless, post apocalyptic wasteland. Not one standing building is to be seen, only crumbling ruins. In contrast, the comic feels more primordial and more alien. The stars are so close and bright they shine even during daytime. Early in the comic, Noah travels to the dystopian metropolis of Bab-ilIm - "A city so vast it took a planet of spoil to stuff its ravenous maw" - and gazes upon its legendary tower. Its byzantine structure referencing both ancient temples and futuristic skyscrapers.

One of the strengths of the graphic novel is that Henrichon has more space to mould this fantastic world, from the exotic megafauna that populate it, to the mysterious Watchers - the Nephilim of Genesis, to Noah's shamanic grandfather Methuselah. Henrichon's designs are usually more grandiose than anything used in the film.

The drawback though is that the story becomes bloated in its attempts to cultivate its many parts. Not only is Noah racing to complete the Ark before the rains come, he's fending of hordes of refugees from Bab-ilIm led by the violent Tubal-cain, enlisting the Watchers to his cause, keeping his increasingly doubtful family in line, all while trying to decode the will of the Creator. The result is that the comic has not one, but several climactic scenes piling on top of each other.

The one area where Henrichon clearly falls short as an artist is in his character designs for Noah's family. They aren't written with very distinctive personalities to begin with, and after awhile, they all even morph to look rather interchangeable. This is where the film's cast does a better job in fleshing them out, particularly Emma Watson as long suffering daughter-in-law Ila and Logan Lerman as the much abused middle son Ham.

Both versions ultimately flounder from wanting to have its cake and eat it. Is the story aiming for spiritual transcendence or exposing the folly of blind faith, or both? The narrative doesn't quite cohere. In an important scene, Noah recounts the Genesis creation story to his family. His words are overlaid over a montage of images illustrating the Big Bang, the formation of the first galaxies and stars, the birth of our solar system, and the evolution of life from organic molecules all the way to primates. It's a provocative way to illustrate the tale. Although in this case the film's use of strobe effects and digital imagery is way cooler than Henrichon's still images, which feel kind of textbook in comparison.

In contrast to this allegorical interpretation optimized to coexist with the prevailing scientific world view, Aronofsky takes the story of the Flood at face value. So we still get the usual imagery such as the procession of the animals into a gigantic wooden box, or a deluge that blankets the entire world while drowning everything on land, which presumably includes a lot of plant and animal life as collateral damage for humankind's folly. We still have to accept the bizarre premise that an Ark could restore the planet's biodiversity with only a tiny sampling from each species and isn't just an idiotic scheme cooked up by a deranged individual. Given Aronofsky's monomaniacal portrait of Noah, it's a pretty tough sell.

Art: Niko Henrichon

Letters: Nicolas Sénégas

Design: Tom Muller

The Biblical myth of the Flood is a dark tale about an all-powerful but petulant god who regrets creating humanity and decides to drown them all in a worldwide deluge. But he makes an exception for Noah and his family. Noah himself barely mutters a peep as he carries out God's commands without fail, like any trusted servant. God's act of universal destruction serves to complement the Genesis story of his creation of the world. But In Darren Aronofsky's retelling, God is absent. The psychodrama instead falls on Noah as he struggles to understand the deity's will, which he believes is being communicated to him through visions so cryptic they often leave him conflicted about their true meaning. His crisis of faith becomes the focal point in an ambitious story that attempts to weave ancient myth, medieval theology, and modern science into a heavy handed morality tale about human greed and environmental despoilation.

While the graphic novel functions as a standalone story, it's interesting to see how it compares to the film. Noah is humanity's first vegan/eco-terrorist/doomsday prepper, disapproving of civilization's wasteful practices and figuring out that the world is going to end. He's even more imposing in the comic, recognized by others as a great warrior and mage. Aronofsky and co-writer Ari Handel teamed-up with artist Niko Henrichon for the comic well before the film was produced, so it's visuals bear almost no resemblance to the film. Noah is drawn as a cape wearing, long-haired, square-jawed heroic type who wouldn't look out of place within a Robert E. Howard fantasy novel or a Thor comic. His appearance takes on a more sinister aspect down the line as he evolves into a full-blown religious zealot.

But the people Noah actually terrorizes are his own family, whom he's already sequestered from society when the story begins. God's reticence towards Noah in Genesis is translated in this humanistic adaptation as Noah's confusion as to whether God (dubbed the "Creator") intends for humanity to survive or go extinct. Like in the film, his increasing conviction that Original Sin has made them unworthy of the the former creates a rift with his family. And his behavior is far more extreme in the comic. At one point, he even sets the animals of the Ark against them when they defy him. This Noah takes no prisoners.

Henrichon's antediluvian setting is also visually striking. One of the underwhelming things about the film was its subdued palette suggesting a burnt out, featureless, post apocalyptic wasteland. Not one standing building is to be seen, only crumbling ruins. In contrast, the comic feels more primordial and more alien. The stars are so close and bright they shine even during daytime. Early in the comic, Noah travels to the dystopian metropolis of Bab-ilIm - "A city so vast it took a planet of spoil to stuff its ravenous maw" - and gazes upon its legendary tower. Its byzantine structure referencing both ancient temples and futuristic skyscrapers.

One of the strengths of the graphic novel is that Henrichon has more space to mould this fantastic world, from the exotic megafauna that populate it, to the mysterious Watchers - the Nephilim of Genesis, to Noah's shamanic grandfather Methuselah. Henrichon's designs are usually more grandiose than anything used in the film.

The drawback though is that the story becomes bloated in its attempts to cultivate its many parts. Not only is Noah racing to complete the Ark before the rains come, he's fending of hordes of refugees from Bab-ilIm led by the violent Tubal-cain, enlisting the Watchers to his cause, keeping his increasingly doubtful family in line, all while trying to decode the will of the Creator. The result is that the comic has not one, but several climactic scenes piling on top of each other.

The one area where Henrichon clearly falls short as an artist is in his character designs for Noah's family. They aren't written with very distinctive personalities to begin with, and after awhile, they all even morph to look rather interchangeable. This is where the film's cast does a better job in fleshing them out, particularly Emma Watson as long suffering daughter-in-law Ila and Logan Lerman as the much abused middle son Ham.

Both versions ultimately flounder from wanting to have its cake and eat it. Is the story aiming for spiritual transcendence or exposing the folly of blind faith, or both? The narrative doesn't quite cohere. In an important scene, Noah recounts the Genesis creation story to his family. His words are overlaid over a montage of images illustrating the Big Bang, the formation of the first galaxies and stars, the birth of our solar system, and the evolution of life from organic molecules all the way to primates. It's a provocative way to illustrate the tale. Although in this case the film's use of strobe effects and digital imagery is way cooler than Henrichon's still images, which feel kind of textbook in comparison.

In contrast to this allegorical interpretation optimized to coexist with the prevailing scientific world view, Aronofsky takes the story of the Flood at face value. So we still get the usual imagery such as the procession of the animals into a gigantic wooden box, or a deluge that blankets the entire world while drowning everything on land, which presumably includes a lot of plant and animal life as collateral damage for humankind's folly. We still have to accept the bizarre premise that an Ark could restore the planet's biodiversity with only a tiny sampling from each species and isn't just an idiotic scheme cooked up by a deranged individual. Given Aronofsky's monomaniacal portrait of Noah, it's a pretty tough sell.

5/06/2015

Stamp Collecting

3/15/2015

2/28/2015

R.I.P. Leonard Nimoy (1913-2015)

Photo courtesy of NASA

From Star Trek/X-Men

Photo Courtesy of R. Michelson Galleries

Of all the souls I have encountered in my travels, his was the most human.In an era when nerd heroes were still in short supply, Mr. Spock was already there. Bon voyage Leonard Nimoy. You lived and prospered.

- Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

1/16/2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)