By Box Brown

Box Brown has made a career uncovering the stories behind pop culture objects of a very specific milieu, namely early 80s Americana. He’s authored biographies about two infamous celebrities: pro wrestler André the Giant, and comedian Andy Kaufman. With last year’s Tetris: The Games People Play, Brown instead tackled a video gaming classic. The resulting graphic novel reveals that his approach to biography works just as well for talking about nonhuman subjects. After all, Tetris didn’t just emerge from the void like one of its signature puzzle pieces. Someone had to invent it, and others had to fall for its charms. Some people might be aware that the game was the brainchild of computer scientist Alexey Pajitnov, when he was still working at the Academy of Science in Moscow. Even fewer will know what measures were taken to export the game to the Western world during the final stages of the Cold War. Brown’s examination of the complex business machinations behind Tetris’ international success is very accessible because he keeps the attention centered on the personalities involved, and not on the technologies that made it possible.

Before getting into the story of Tetris, Brown lays out his thesis for the comic. His short examination of the history (and prehistory) of games leads him to conclude that they are an artistic enterprise, the creative fusion of the competitive spirit and the child’s act of playing. Games nurture analytical skills and model human behavior by connecting with the audience’s desire for diversion, whether it be the ancient board game of Senet, the 19th century Japanese card game Hanafuda, or the video game consoles manufactured by Nintendo and Atari during the early 1980s. Every games’ popularity is a reflection of their respective society. With Tetris, Alexey’s own contribution to history was to combine the pleasures of classic puzzle games with real-time problem solving made possible by video games into an endlessly iterating loop.

Alexey himself isn’t one of Brown’s more enigmatic protagonists. He’s portrayed as a Steve Wozniak type of figure who created Tetris in 1984, during his free time in order to give expression to his ideas and entertain his friends. He showed no interest in profiting from his creation. The game would soon become a viral hit in Moscow, shared through floppy discs. A version of Tetris would make its way to Hungary, where it would be discovered by Robert Stein of U.K.-based Andromeda Software.

From here, the story becomes a lot more complicated as Alexey gradually loses control of his own creation. Various American and Japanese companies would vie for the distribution rights to Tetris, and at some point had to negotiate directly with the Russian government agency named Elorg. Like many tales from the nascent personal computing and video gaming industry, many of the parties involved were stumbling over a mess of patent, copyright, and trademark issues. Tetris would be ported to virtually every popular computing platform even when the legality of its distribution was still far from settled. This confusing state of affairs would eventually culminate in a huge 1993 legal battle between Nintendo and Atari.

If Brown were appealing just to the gaming crowd, he’d get lost comparing the varieties of Tetris being produced during this time, and judging each on their technical merits. That would make for an unwieldy comic. Thankfully, he’s more interested in the various business personalities fighting for a piece of the game. His chapter breaks are structured around their involvement, each character being helpfully introduced with a formal portrait and accompanying caption, isolated on the page by inky black. His blocky cartoon style is even more minimalist than in Andre the Giant, all the better to facilitate his understated, third person narrative voice. The only thing keeping the art from becoming completely flat is Brown’s choice of vibrant yellow to add volume to his black and white forms. But Brown is first and foremost, a storyteller. The comic still proves to a page turner despite the large cast of characters and numerous plot twists.

With everything said, Brown’s sympathies lie ultimately with the humble Alexey. He sees him as a master of his craft. Alexey wanted more than anything for the world to know his beloved game. As he explained during a 2015 appearance: “If I made a big fuss about the money, they would immediately have crushed my efforts. They would have crushed Tetris. Tetris would have been left without a champion to stick up for it and guide it. We would not be here today.”

Showing posts with label black and white. Show all posts

Showing posts with label black and white. Show all posts

12/17/2017

11/30/2017

More NonSense: Eddie Berganza vs C.B. Cebulski

Eddie Berganza

Thor: Ragnarok, which was inspired by Marvel's comics adaptations of the Norse apocalypse, and fan favourite story Planet Hulk, is the 16th film from the ongoing Marvel cinematic universe. It's as solid an entry as any of them, with a healthy dose of swashbuckling space adventure more typically associated with Guardians of the Galaxy. But as a continuation of several plot threads going all the way back to 2011, it works very much like the middle chapter to a bigger story. This hasn't hurt its box office performance or dampened enthusiasm for the MCU. If anything, people want to know how it will pan out in the end.

What does set it apart is how it ties together Thor's sordid family history into a pointed commentary on the revisionist nature of imperialism.

Abraham Riesman lists five Thor comics to read before seeing the latest film. He also recommends eight comics for November.

Justice League is the other superhero tent film of November, and has opposite concerns. The news isn't good for those hoping it would build upon the positive reception of Wonder Woman. Much like Zach Snyder's past directorial contributions to DC's cinematic universe, Justice League is overstuffed with references that are mostly unearned. It's a half-formed world trying hard to fool the audience into believing that it's a fully developed universe. Background information is haphazardly doled out about the new characters to make them more sympathetic. But the only reason why Flash and Aquaman are at all likeable is because of the performances of Ezra Miller and Jason Momoa. Overall, Justice League is notable for the ways it sets the stage for the future cinematic universe than for its own modest merits.

The modern superhero film is today's equivalent to the classic movie musical.

Publisher's Weekly lists its best comics for 2017.

Tony Isabella interviewed about his return to the character her created in 1977, Black Lightning.

These Calvin and Hobbes strips are a nice reminder of how we love to exclude outsiders. Seems particularly relevant today.

A page of Maus is lauded for its' aesthetic qualities.

Eddie Berganza was accused of sexual misconduct in a recent Buzzfeed article. Comics professionals reacted. Then DC first suspended Berganza, only to fire him a few days later. Even more women have since come forward. Rumours about Berganza's terrible conduct are nothing new, and DC was criticized in the past for its tepid response. The difference now is that these allegations are finding new life as part of a wave of similar allegations against other powerful male figures within the larger entertainment industry, and society in general.

What's particularly upsetting is how Berganza was tolerated despite having long developed a reputation within the comics community for being a jerk:

But Berganza’s editorial skills aren’t all he’s known for in the comics industry. At best, he developed a reputation for making offensive jokes or line-crossing comments in the presence of or at the expense of women; one former staffer recalls hearing Berganza tell a female assistant that a writer needed to make a character in a book they were editing "less dykey." Asselin recalled Berganza once telling her that the reason he didn't hit on her was because he had too much respect for her spouse. But at worst, he’s alleged to have forcibly kissed and attempted to grope female coworkers. One woman said when she started at DC, she was warned about Berganza — advised to keep an eye on him, she said, and to not get drinks with him. "People were constantly warning other people away from him," said Asselin, a vocal critic of gender dynamics in the comics industry.

Berganza's reputation spread throughout the comics industry, so much so that Sophie Campbell, an established writer and artist, turned down an opportunity to work on a Supergirl comic two years ago because Berganza was the editor overseeing the project, even though she wouldn't have had to speak directly to him during the job. It would've been a cool gig, Campbell told BuzzFeed News, but it also "felt scuzzy and scary."

"I didn't like the idea of being in professional proximity with him or having his name on something I worked on," she said.

A former DC employee said Berganza’s reputation was "something that I didn't like, but I stomached it. Everybody did. It was a gross open secret."

C.B. Cebulski

Meanwhile, editor C.B. Cebulski replaced Alex Alonso as Marvel's Editor in Chief, in a year the publisher experienced weak print sales while making controversial statements. He then admitted on Bleeding Cool that he once masqueraded as a Japanese writer by naming himself Akira Yoshida. He found himself penning comics such as Thor: Son of Asgard, Elektra: The Hand, Wolverine: Soultaker, and Kitty Pryde: Shadow & Flame. This was done to get around Marvel's policy of not allowing staffers to write or draw any of the publisher's comic books.

I stopped writing under the pseudonym Akira Yoshida after about a year. It wasn’t transparent, but it taught me a lot about writing, communication and pressure. I was young and naïve and had a lot to learn back then. But this is all old news that has been dealt with, and now as Marvel’s new Editor-in-Chief, I’m turning a new page and am excited to start sharing all my Marvel experiences with up and coming talent around the globe.Rewarding an employee who once lied to the world about being an Asian man. Way to go, Marvel. That the two biggest publishers in American comics can put up with the actions of a known sexual harasser, and a self-admitted fraud who brushes off his past indiscretions as acceptable for a person of his lofty position, indicates something rotten within this industry.

Sana Amanat has responded to Cebulski's confession by actually defending him. The revelations have also inspired a hashtag bringing more attention to Asian comic creators. Cebulski is part of a long line of writers creating orientalist portrayals at Marvel, and within the comics industry. Though I can't think of any industry insider who went so far as to extend the practice to fudging their race and nationality for pure economic advantage.

Jim Shooter, Marvel's legendary former Editor in Chief, interviewed by Chris Hassan.

Nobuhiro Watsuki, best known as the creator of the manga Rurouni Kenshin, has been arrested for possession of child pornography.

Labels:

alternative,

Art Spiegelman,

Bill Watterson,

black and white,

Calvin and Hobbes,

cartoon,

Commentary,

film,

gender roles,

Hulk,

industry,

JLA,

Justice League,

manga,

porn,

race,

superhero,

Thor

11/27/2017

11/11/2017

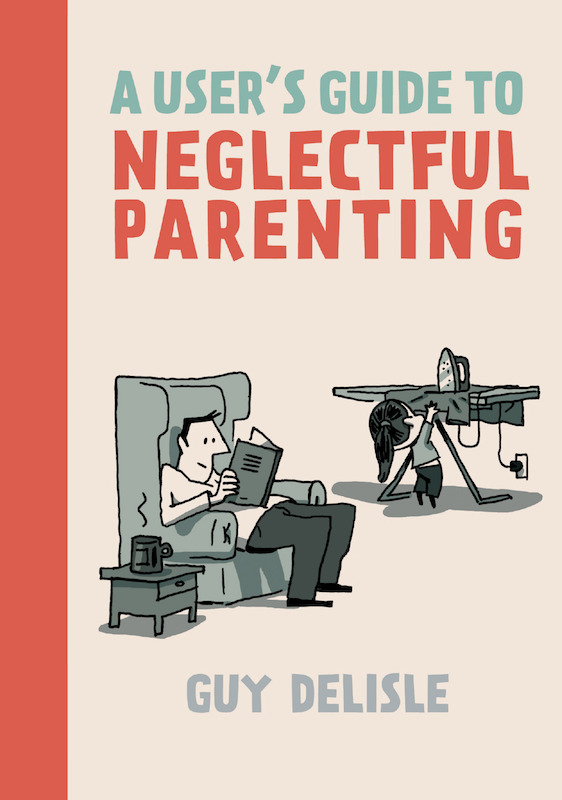

A User’s Guide To Neglectful Parenting

By Guy Delisle

Translation: Helge Dascher

Guy Delisle has earned a reputation as a cartoonist who portrays himself as a hapless explorer. In my review of Jerusalem, I wrote “Noting the strangeness of a place may not be particularly insightful analysis, but it works perfectly for Delisle. His stockpiling of numerous insignificant details mirrors how most clueless Westerners experience the rest of the world. Delisle has become the spokesperson for early stage culture shock because he never achieves true mastery of his subject. Not that he seems to care.” I also observed how raising a family has been increasingly taking up more of Delisle’s time and energy, making his travelogues even more rambling and incidental. His post-Jerusalem work hasn’t shown an appreciable evolution in his basic narrative style, but his storytelling in books like A User’s Guide To Neglectful Parenting have become more manageable by tightening their focus on one aspect of the cartoonist’s life. In this particular case, Delisle collects random anecdotes about his less than stellar approach to caring for two precocious children. And unlike his travelogues, there isn’t an arc connecting these separate incidents.

Delisle adapts the same everyman persona he’s used in the past. This works just as well in conveying his cluelessness when it comes to communicating with kids as it did with the locals of foreign lands. Only this time, he gets to be demonstrably angry and intimidating as a supposably adult authority figure. His level of self-absorption is just enough to be relatable to other harried parents. This results in the kind of dismissive condescension and obliviousness mixed with annoyance the average adult normally exhibits towards children. In the book’s opening story, Delisle neglects to replace his son’s fallen out baby tooth with money for two nights in a row. When the son begins to suspect his parents are the real Tooth Fairy (or its French equivalent), Delisle lies with “If it was us putting the money under your pillow, do you really think we’d forget two nights in a row?” When his son seems unimpressed with the amount of money he received for yet another tooth, a visibly upset Delisle pulls out a one-cent coin and gives the game up by making the threat "Next time I'm gonna give you this here instead of two euros!" The son’s open mouthed reaction is subtle, and hilariously appropriate to the occasion.

In addition to resorting to those kinds of white lies, Delisle engages in even more of the usual parental shenanigans. He pretends to be more informed about subjects where he knows nothing. He feigns interest in his children’s activities. He inadvertently (or deliberately) terrifies them. He occasionally harangues them, especially his son for not showing more interest in traditional manly activities like fixing the house plumbing. Anyone who’s survived their childhood and remembers the hurtful things parents casually heaped on them will understand the often impassive expressions of Delisle’s kids. But they’re also the straight man bearing witness to his inappropriate behavior. When free to write about characters he genuinely cares about without tying them to a larger, sprawling travelogue, Delisle’s humor shapes up to be sharper and funnier.

In the book’s most curious anecdote, Delisle gets to be the curmudgeonly artist reflecting on his own status in the industry. When his daughter brings him one of her drawings for inspection, Delisle does what is expected of any parent and praises her young efforts. But after a slight pause, his inner editor takes over and he begins critiquing the drawing like it’s another magazine submission. He points out all its various technical flaws, then gathers himself once again and launches into an extended rant about young cartoonists and their unwillingness to put in the work and learn proper drawing skills: “I know what you're going to say ... You're going to tell me it's your ‘style’ and that you did it on purpose. Well, kiddo, let me tell you, there's a hell of a difference between drawing like a hack and having some kind of style. Not everybody's Art Spiegelman, you know."

Heh. I wonder from where a younger Delisle heard that from?

Translation: Helge Dascher

Guy Delisle has earned a reputation as a cartoonist who portrays himself as a hapless explorer. In my review of Jerusalem, I wrote “Noting the strangeness of a place may not be particularly insightful analysis, but it works perfectly for Delisle. His stockpiling of numerous insignificant details mirrors how most clueless Westerners experience the rest of the world. Delisle has become the spokesperson for early stage culture shock because he never achieves true mastery of his subject. Not that he seems to care.” I also observed how raising a family has been increasingly taking up more of Delisle’s time and energy, making his travelogues even more rambling and incidental. His post-Jerusalem work hasn’t shown an appreciable evolution in his basic narrative style, but his storytelling in books like A User’s Guide To Neglectful Parenting have become more manageable by tightening their focus on one aspect of the cartoonist’s life. In this particular case, Delisle collects random anecdotes about his less than stellar approach to caring for two precocious children. And unlike his travelogues, there isn’t an arc connecting these separate incidents.

Delisle adapts the same everyman persona he’s used in the past. This works just as well in conveying his cluelessness when it comes to communicating with kids as it did with the locals of foreign lands. Only this time, he gets to be demonstrably angry and intimidating as a supposably adult authority figure. His level of self-absorption is just enough to be relatable to other harried parents. This results in the kind of dismissive condescension and obliviousness mixed with annoyance the average adult normally exhibits towards children. In the book’s opening story, Delisle neglects to replace his son’s fallen out baby tooth with money for two nights in a row. When the son begins to suspect his parents are the real Tooth Fairy (or its French equivalent), Delisle lies with “If it was us putting the money under your pillow, do you really think we’d forget two nights in a row?” When his son seems unimpressed with the amount of money he received for yet another tooth, a visibly upset Delisle pulls out a one-cent coin and gives the game up by making the threat "Next time I'm gonna give you this here instead of two euros!" The son’s open mouthed reaction is subtle, and hilariously appropriate to the occasion.

In addition to resorting to those kinds of white lies, Delisle engages in even more of the usual parental shenanigans. He pretends to be more informed about subjects where he knows nothing. He feigns interest in his children’s activities. He inadvertently (or deliberately) terrifies them. He occasionally harangues them, especially his son for not showing more interest in traditional manly activities like fixing the house plumbing. Anyone who’s survived their childhood and remembers the hurtful things parents casually heaped on them will understand the often impassive expressions of Delisle’s kids. But they’re also the straight man bearing witness to his inappropriate behavior. When free to write about characters he genuinely cares about without tying them to a larger, sprawling travelogue, Delisle’s humor shapes up to be sharper and funnier.

In the book’s most curious anecdote, Delisle gets to be the curmudgeonly artist reflecting on his own status in the industry. When his daughter brings him one of her drawings for inspection, Delisle does what is expected of any parent and praises her young efforts. But after a slight pause, his inner editor takes over and he begins critiquing the drawing like it’s another magazine submission. He points out all its various technical flaws, then gathers himself once again and launches into an extended rant about young cartoonists and their unwillingness to put in the work and learn proper drawing skills: “I know what you're going to say ... You're going to tell me it's your ‘style’ and that you did it on purpose. Well, kiddo, let me tell you, there's a hell of a difference between drawing like a hack and having some kind of style. Not everybody's Art Spiegelman, you know."

Heh. I wonder from where a younger Delisle heard that from?

10/14/2017

A City Inside

By Tillie Walden

A City Inside Is a tone poem crafted with appreciable virtuosity. It begins with an unnamed young woman lying on a divan while conversing with an unseen individual. From the manner of their conversation, it becomes apparent that the woman is inside a therapist’s office and preparing to go through some form of regression therapy. She enters into the requisite dream state by being gently absorbed by the divan. The sequence works because of how it’s illustrated by Tillie Walden with beautiful minimalism. The divan’s sloping form and repeating patterns make it appear as if the woman is floating on the surface of a large body of water. And when she sinks into the divan with the assistance of the therapist, the sequence recalls the experience of baptism or of retreating into the innocence of one's childhood.

The central conflict which prompts this bout of self-examination is a personal struggle - at its most abstract it’s a choice between love and freedom. Or maybe it’s between stability and personal growth. Or reality or fantasy. The message is open to interpretation. Whatever the case, the struggle is viewed as a reverie composed of a series of phantasmagorical images. The therapist serves as the narrative voice which ties them together, since the woman remains silent once she goes under. But the overall impression of her life is of someone constantly seeking solitude. We first see the woman as a little girl growing up in a large house located in “the South.” The narrator claims that she was happy living with just her father to keep her company. But virtually every panel portrays her being alone with her thoughts, engulfed by the long shadows cast by the house and her rural environment. It doesn’t actually come as a surprise when the narrator says that she left her father when she was only 15, “trying to escape those southern ghosts.”

When we see the woman again, she’s already a young adult living contentedly in the sky. She spends her time writing stories about nonexistent places she wants to visit. Then one night, she meets another woman bicycling past her home. The two begin a romantic relationship, which brings them both back to earth. Only this earthbound existence doesn’t suit our protagonist, who begins to contemplate leaving her lover. But the uncomplicated narrative belies the artistic challenge of capturing its contrasting environments. Walden accomplishes this through her skillful use of black and white composition. Inky shadows and silhouette figures balance areas of bright white, and the resulting shapes generate a pleasing rhythm throughout the comic. Textures and patterns create subtle visual motifs which are better appreciated through repeated readings. On a more surface level, Walden’s quiet, dreamlike imagery evokes the surreal landscapes found in the work of classic cartoonists Winsor McCay and George Herriman.

The resolution to her conflict is as fantastic as it is ambiguous. As the therapist’s voice makes the woman consider her future, the surreal landscape she inhabits suddenly expands into an immense and beautiful city. Every object and structure within it embodies some part from her life. But as she wanders the empty metropolis as a much older figure, her final thoughts turn to the people she knew, cared for, and eventually left behind. It’s still a future the woman has yet to choose when she comes out of her reverie and leaves the office. And that tantalizing conclusion makes for a more appealing comic.

A City Inside Is a tone poem crafted with appreciable virtuosity. It begins with an unnamed young woman lying on a divan while conversing with an unseen individual. From the manner of their conversation, it becomes apparent that the woman is inside a therapist’s office and preparing to go through some form of regression therapy. She enters into the requisite dream state by being gently absorbed by the divan. The sequence works because of how it’s illustrated by Tillie Walden with beautiful minimalism. The divan’s sloping form and repeating patterns make it appear as if the woman is floating on the surface of a large body of water. And when she sinks into the divan with the assistance of the therapist, the sequence recalls the experience of baptism or of retreating into the innocence of one's childhood.

The central conflict which prompts this bout of self-examination is a personal struggle - at its most abstract it’s a choice between love and freedom. Or maybe it’s between stability and personal growth. Or reality or fantasy. The message is open to interpretation. Whatever the case, the struggle is viewed as a reverie composed of a series of phantasmagorical images. The therapist serves as the narrative voice which ties them together, since the woman remains silent once she goes under. But the overall impression of her life is of someone constantly seeking solitude. We first see the woman as a little girl growing up in a large house located in “the South.” The narrator claims that she was happy living with just her father to keep her company. But virtually every panel portrays her being alone with her thoughts, engulfed by the long shadows cast by the house and her rural environment. It doesn’t actually come as a surprise when the narrator says that she left her father when she was only 15, “trying to escape those southern ghosts.”

When we see the woman again, she’s already a young adult living contentedly in the sky. She spends her time writing stories about nonexistent places she wants to visit. Then one night, she meets another woman bicycling past her home. The two begin a romantic relationship, which brings them both back to earth. Only this earthbound existence doesn’t suit our protagonist, who begins to contemplate leaving her lover. But the uncomplicated narrative belies the artistic challenge of capturing its contrasting environments. Walden accomplishes this through her skillful use of black and white composition. Inky shadows and silhouette figures balance areas of bright white, and the resulting shapes generate a pleasing rhythm throughout the comic. Textures and patterns create subtle visual motifs which are better appreciated through repeated readings. On a more surface level, Walden’s quiet, dreamlike imagery evokes the surreal landscapes found in the work of classic cartoonists Winsor McCay and George Herriman.

The resolution to her conflict is as fantastic as it is ambiguous. As the therapist’s voice makes the woman consider her future, the surreal landscape she inhabits suddenly expands into an immense and beautiful city. Every object and structure within it embodies some part from her life. But as she wanders the empty metropolis as a much older figure, her final thoughts turn to the people she knew, cared for, and eventually left behind. It’s still a future the woman has yet to choose when she comes out of her reverie and leaves the office. And that tantalizing conclusion makes for a more appealing comic.

7/12/2017

6/24/2017

Loverboys

By Gilbert Hernandez

Gilbert Hernandez made his mark early in the alternative comics market of the 1980s with his stories centering around Palomar - a fictional village located somewhere in Latin America. For over a decade, he weaved a complex tapestry of melancholic tales about small town love and intrigue using Palomar’s unconventional inhabitants. Hernandez has more recently moved away from these longform stories to shorter, more self-contained comics. But Loverboys will feel familiar to fans of Palomar. There’s the small town setting. A varied ensemble of individuals linked to each other by who they slept with, or who they want to sleep with. Unspoken rivalries bubbling beneath the surface. Voluptuous feminine figures with a mysterious past. An enigmatic supernatural element haunting his cast and informing their actions. All this is drawn in his signature cartooning style. But at barely eighty pages, Hernandez has distilled these components down to their bare essentials. The result is a story that tamps down on its more flamboyant soap opera aspects to exhibit greater emotional restraint. Not that Hernandez isn’t already an intelligent storyteller, but this narrative seems slightly more calculated.

The restraint is somewhat surprising given that the book’s front cover captures two of its principal characters in an intimate moment. But much of the sexual activity takes place off panel. And there’s even less outright violence. So much of the storytelling in Loverboys is economical. Hernandez’s art is perhaps even more starkly minimalist, if that’s even possible. His traditional page layouts, simple perspective, and uncluttered panel compositions function as an simple stage for his cast, which are always designed to be visually eclectic. Actually, this is a huge cast for such a comparatively short comic, so not all of them can receive equal attention. But the reader can easily spot several of them in the background either casually observing or surreptitiously eavesdropping on the foregrounded characters. This all serves to reinforce the gossipy nature of a tiny community.

The minimalist visuals are complemented by the book’s spare dialogue. With the exception of the establishing pages used to introduce the fictional setting of Lágrimas, there’s very little exposition to describe the actions of the cast. Almost nothing is revealed of the inner lives of the minor characters. But the observant reader will notice some of them going through their own individual arcs. Clues are found in their actions, facial expressions, and offhand remarks. Even information about the central characters is divulged gradually: one crucial detail which helps to illuminate their motivations is delivered in a casual aside sometime past the halfway point.

At the heart of the story is the May-December romance of young lothario Rocky and his former substitute teacher Mrs. Paz, and the effect this has on Rocky’s little sister Daniela, who happens to be Mrs. Paz’s current student. The relationship and its eventual dissolution isn’t in itself all that remarkable. What is compelling is how Hernandez is able to map how it creates ripples throughout Lágrimas. As the town’s resident pretty boy, Rocky’s romantic interest in the elderly Mrs. Paz sparks a considerable amount of interest. And as their relationship begins to flounder, Mrs. Paz is suddenly eyed by a random collection of singles - from the unlovable loser who’s never dated anyone, another would-be womanizer, a pair of creepy twins, to even a lonely schoolgirl. Through separate interactions with each of them, some of them sexual, Mrs. Paz in turn either embarrasses, humiliates, or enables them. Hernandez handles these scenes with his characteristic mix of empathy for his cast’s frailties while delighting (even sometimes indulging) in human sensual pleasures. Only this time his approach is a little more compressed.

Loverboys may not contain the narrative intricacy, sustained world building, or emotional highs of his earlier work. That’s not likely. But there’s something to be said when a talent like Gilbert Hernandez tackles new formats. If this is a lesser work, it’s still more accomplished than most comics being currently published. Or to quote one of the characters in the book, “I think it’s beautiful.”

Gilbert Hernandez made his mark early in the alternative comics market of the 1980s with his stories centering around Palomar - a fictional village located somewhere in Latin America. For over a decade, he weaved a complex tapestry of melancholic tales about small town love and intrigue using Palomar’s unconventional inhabitants. Hernandez has more recently moved away from these longform stories to shorter, more self-contained comics. But Loverboys will feel familiar to fans of Palomar. There’s the small town setting. A varied ensemble of individuals linked to each other by who they slept with, or who they want to sleep with. Unspoken rivalries bubbling beneath the surface. Voluptuous feminine figures with a mysterious past. An enigmatic supernatural element haunting his cast and informing their actions. All this is drawn in his signature cartooning style. But at barely eighty pages, Hernandez has distilled these components down to their bare essentials. The result is a story that tamps down on its more flamboyant soap opera aspects to exhibit greater emotional restraint. Not that Hernandez isn’t already an intelligent storyteller, but this narrative seems slightly more calculated.

The restraint is somewhat surprising given that the book’s front cover captures two of its principal characters in an intimate moment. But much of the sexual activity takes place off panel. And there’s even less outright violence. So much of the storytelling in Loverboys is economical. Hernandez’s art is perhaps even more starkly minimalist, if that’s even possible. His traditional page layouts, simple perspective, and uncluttered panel compositions function as an simple stage for his cast, which are always designed to be visually eclectic. Actually, this is a huge cast for such a comparatively short comic, so not all of them can receive equal attention. But the reader can easily spot several of them in the background either casually observing or surreptitiously eavesdropping on the foregrounded characters. This all serves to reinforce the gossipy nature of a tiny community.

The minimalist visuals are complemented by the book’s spare dialogue. With the exception of the establishing pages used to introduce the fictional setting of Lágrimas, there’s very little exposition to describe the actions of the cast. Almost nothing is revealed of the inner lives of the minor characters. But the observant reader will notice some of them going through their own individual arcs. Clues are found in their actions, facial expressions, and offhand remarks. Even information about the central characters is divulged gradually: one crucial detail which helps to illuminate their motivations is delivered in a casual aside sometime past the halfway point.

At the heart of the story is the May-December romance of young lothario Rocky and his former substitute teacher Mrs. Paz, and the effect this has on Rocky’s little sister Daniela, who happens to be Mrs. Paz’s current student. The relationship and its eventual dissolution isn’t in itself all that remarkable. What is compelling is how Hernandez is able to map how it creates ripples throughout Lágrimas. As the town’s resident pretty boy, Rocky’s romantic interest in the elderly Mrs. Paz sparks a considerable amount of interest. And as their relationship begins to flounder, Mrs. Paz is suddenly eyed by a random collection of singles - from the unlovable loser who’s never dated anyone, another would-be womanizer, a pair of creepy twins, to even a lonely schoolgirl. Through separate interactions with each of them, some of them sexual, Mrs. Paz in turn either embarrasses, humiliates, or enables them. Hernandez handles these scenes with his characteristic mix of empathy for his cast’s frailties while delighting (even sometimes indulging) in human sensual pleasures. Only this time his approach is a little more compressed.

Loverboys may not contain the narrative intricacy, sustained world building, or emotional highs of his earlier work. That’s not likely. But there’s something to be said when a talent like Gilbert Hernandez tackles new formats. If this is a lesser work, it’s still more accomplished than most comics being currently published. Or to quote one of the characters in the book, “I think it’s beautiful.”

3/17/2017

1/20/2017

More NonSense: March

TCJ lists their best comics of 2016.

2017 marks the 25th anniversary of the Pulitzer Prize awarded to landmark comix Maus. Women Write About Comics holds a roundtable about the work. Last year's article by Michael Cavna quotes several comics creators who were influenced by Maus, including Gene Yang, Chris Ware, and Jeff Smith.

March is the best selling book on Amazon, just in time for Martin Luther King Day.

Isaac Butler compares the story of John Lewis in March and the presidency of Barack Obama.

Who would have thought Superman's red shorts would have become a hot political issue? Comics, folks.

Barack Obama on the power of fiction and storytelling.

Chris Ware, Cosey and Larcenet are three finalists for Angoulême’s Grand Prix, while Alan Moore steps aside again.

The Winter Issue of the Martial Arts Studies is available for download.

Ben Judkins on the limits of authenticity in martial arts. Who would have thought these kinds of discussions would eventually include lightsaber combat?

Labels:

alternative,

Angoulême,

Art Spiegelman,

Barack Obama,

black and white,

Chris Ware,

Commentary,

convention,

election 2016,

fighting arts,

industry,

March,

politics,

race,

Star Wars,

superhero,

Superman

11/02/2016

More Nonsense: Ms. Marvel Will Save You Now

|

| Three Marvel interpretations of Kamala Khan surround fan Meevers Desu as Ms. Marvel at the Denver Comic Con. |

Barbara Calderón interviews Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez.

Sean T. Collins lists the greatest graphic novels of all time.

Heidi MacDonald on the contradiction that is Wonder Woman as a U.N. Honorary Ambassador.

R.I.P. Jack Chick (April 13, 1924-October 23, 2016). Tributes by Benito Cereno, Sean Kleefeld, Heidi MacDonald, Joe McCulloch,

Just a reminder: Scott Adams is nuts.

Charles Russo deciphers Bruce Lee vs. Wong Jack Man.

Lucasfilm sues New York Jedi over trademark infringement. I've been wandering when Lucas/Disney would go after any of the numerous lightsaber academies.

Labels:

alternative,

black and white,

cartoon,

Commentary,

fighting arts,

gender roles,

Gilbert Hernandez,

Jack Chick,

Jaime Hernandez,

Kamala Khan,

Ms. Marvel,

politics,

race,

religion,

Scott Adams,

Star Wars,

superhero,

Wonder Woman

7/31/2016

Wizzywig: Portrait of a Serial Hacker

By Ed Piskor.

The cover for the graphic novel Wizzywig is slightly deceptive. The title is a play on the acronym WYSIWYG, which stands for the “What You See Is What You Get” feature of the modern graphic user interphase. The cover design for the Top Shelf edition (the comic originated as a serialized webcomic before being self-published in 3 volumes) evokes the case of an early model Apple Macintosh running MacPaint. But creator Ed Piskor is less interested in the birth of desktop publishing than in the world of phone phreaking, war dialing, and other activities associated with old-school computer hackers. Piskor’s art style descends from the line of satirical cartooning that began with the Underground Comix movement of the 60s and continued with the alt cartoonists of succeeding decades. So it’s well suited to drawing a clear parallel between the outsider status of cartoonists and hackers while pillorying those who persecute them.

Given its almost 300 pages of densely composed panels and scope of subject matter, the comic is not a quick read. Piskor channels the first 20-odd years of computer hacking through his main protagonist Kevin Phenicle, a composite of several famous real world hackers (namely Kevin Mitnick, Mark Abene and Kevin Poulsen, with a dash of Josef Carl Engressia, Jr). Going by the internet handle “Boingthump”, he occasionally runs into tech legends like Robert Morris or the pre-Apple Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. The comic begins with a series of talking heads giving contradictory opinions about Kevin. As people either vilify or idolize him, an overall picture emerges of a near-mythical figure who’s nonetheless deeply misunderstood by the public. The scene quickly shifts to a radio show hosted by Kevin’s childhood friend Winston Smith (a reference to Off the Hook, a radio show hosted by Emmanuel Goldstein). Winston informs his audience that Kevin is currently being imprisoned without trial and agitates for the government giving him his proper due process. The scene shifts again to reveal a much younger Kevin being bullied by two kids while waiting for the school bus.

Piskor uses these vignettes as the basic building blocks of his narrative. While Kevin’s formative years enfold in a mostly episodic manner, the comic regularly flash forwards to adult Kevin’s incarceration. Mixed in are excerpts of Winston’s radio show, more interviews with random people on the street, television news reports, and scenes involving other more relevant characters. This structure affords Piskor the ability to easily shift forwards and backwards in time. But it’s also calculated to make the esoteric subject of computer hacking more comprehensible to the layperson. Certain sections inevitably go into detail about Kevin’s exploits, whether that be discovering a security flaw in the punch card system used by bus lines, scamming a delivery place to score some free pizza, pirating computer games, pranking members of a local BBS, or undermining the monopolistic power of Ma Bell, the act that would finally earn Kevin the unwelcome scrutiny of the Powers-that-be. Piskor’s explanations are short, not too complicated to follow, and easily digestible to the non-technical reader.

Wizzywig is a pretty good showcase of how a cartoonist maintains narrative momentum even when the characters are engaged in fairly mundane tasks. Like Chester Brown in Louis Riel, Piskor mostly sticks to the highly readable 6-panel grid layout. Characters in conversation or deep in thought are often shown walking from place to place. Or drawn in different poses and shifting perspectives if they’re merely sitting. Piskor’s eye for gritty detail is quite efficient in conveying setting and mood, but it’s his gift for caricature that stands out. No one's physical features are flattered, no matter however attractive. People often seem to possess odd proportions or carry themselves with terrible body posture. Most of them have big noses, sallow skin, shaggy hair, beady eyes. In contrast, Kevin’s impossibly poofy hair and pupiless eyes (again recalling Riel and Little Orphan Annie) suggests a potent mixture of innocence and craftiness.

At first glance, Kevin would appear to be the stereotypical nerdy kid who’s a whiz with computers, but has no friends or can’t get laid. But he’s an orphan living with a grandmother who’s incapable of providing him with enough adult supervision, or dole out the kind of practical advice on how to deal with school bullies. Kevin’s hacking doesn’t just arise from boredom or intellectual curiosity, but also from an impulse to strike back at his oppressors. Hacking becomes a non-physical form of asymmetrical warfare. The irony is that for all his social awkwardness, Kevin becomes particularly adept at what the industry calls “social engineering,” manipulating the behavior of other people to obtain information and get them to do what he wants. But his cunning also belies a deep naivete that leads to his eventual undoing. An early sign of things to come is when Kevin illegally resells gaming software, but as a joke inserts a bit of extra code into the program which will display the message “Boingthump owns your soul, sucka!” after 100 plays. Unfortunately this renders the game unplayable, and Kevin earns the ire of local gamers. More ominously, the code’s ability to infect whatever system the game’s installed into also gains media attention, and the name Boingthump becomes associated with computer viruses.

Kevin becomes a fugitive from the law around the halfway point, living a day-to-day nomadic existence. It turns out that the resourcefulness he’s displayed are particularly useful to life on the run. Much of this part of the book is still spent on educating the reader about various hacks: how to assume a false identity, find temp work, and not draw attention to oneself. Kevin runs a number of hustles just to stay alive. One particular scheme involves rigging numerous radio contests and recruiting women to claim the prize, usually taking the cash items for himself. His social engineering takes on an even more mercenary overtone, and Kevin’s portrayal becomes somewhat dehumanized as a result.

This part of the comic is where Piskor’s satire is at full force. The mainstream media’s treatment of hackers is embodied by a muckraking television journalist whose thick mustache and ludicrous combover makes him look like an older, evil version of Kevin. His reports on Kevin’s alleged crimes become increasingly sensationalized, with both the FBI and the Ma Bell only too happy to participate in the vilification process. Winston becomes the sole voice of reason in this climate of media-induced paranoia.

A side effect of this shift in tone is that Kevin becomes more a symbol of systematic injustice than a fully fleshed out individual. The earlier part of the book helped establish him as a sympathetic, if flawed human being. But his character development stalls as he becomes a fugitive, and later a prisoner. It becomes less about Kevin himself than his mistreatment at the hands of his captors. This saps the story’s intended emotional impact when Kevin’s grim experiences are connected to the wider world and latter day whistleblowers, such as Pfc. Bradley Manning and Wikileaks. It’s the most glaring weakness in a highly ambitious work which actually has something relevant to say about the present-day terrifying state of American politics.

The cover for the graphic novel Wizzywig is slightly deceptive. The title is a play on the acronym WYSIWYG, which stands for the “What You See Is What You Get” feature of the modern graphic user interphase. The cover design for the Top Shelf edition (the comic originated as a serialized webcomic before being self-published in 3 volumes) evokes the case of an early model Apple Macintosh running MacPaint. But creator Ed Piskor is less interested in the birth of desktop publishing than in the world of phone phreaking, war dialing, and other activities associated with old-school computer hackers. Piskor’s art style descends from the line of satirical cartooning that began with the Underground Comix movement of the 60s and continued with the alt cartoonists of succeeding decades. So it’s well suited to drawing a clear parallel between the outsider status of cartoonists and hackers while pillorying those who persecute them.

Given its almost 300 pages of densely composed panels and scope of subject matter, the comic is not a quick read. Piskor channels the first 20-odd years of computer hacking through his main protagonist Kevin Phenicle, a composite of several famous real world hackers (namely Kevin Mitnick, Mark Abene and Kevin Poulsen, with a dash of Josef Carl Engressia, Jr). Going by the internet handle “Boingthump”, he occasionally runs into tech legends like Robert Morris or the pre-Apple Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. The comic begins with a series of talking heads giving contradictory opinions about Kevin. As people either vilify or idolize him, an overall picture emerges of a near-mythical figure who’s nonetheless deeply misunderstood by the public. The scene quickly shifts to a radio show hosted by Kevin’s childhood friend Winston Smith (a reference to Off the Hook, a radio show hosted by Emmanuel Goldstein). Winston informs his audience that Kevin is currently being imprisoned without trial and agitates for the government giving him his proper due process. The scene shifts again to reveal a much younger Kevin being bullied by two kids while waiting for the school bus.

Piskor uses these vignettes as the basic building blocks of his narrative. While Kevin’s formative years enfold in a mostly episodic manner, the comic regularly flash forwards to adult Kevin’s incarceration. Mixed in are excerpts of Winston’s radio show, more interviews with random people on the street, television news reports, and scenes involving other more relevant characters. This structure affords Piskor the ability to easily shift forwards and backwards in time. But it’s also calculated to make the esoteric subject of computer hacking more comprehensible to the layperson. Certain sections inevitably go into detail about Kevin’s exploits, whether that be discovering a security flaw in the punch card system used by bus lines, scamming a delivery place to score some free pizza, pirating computer games, pranking members of a local BBS, or undermining the monopolistic power of Ma Bell, the act that would finally earn Kevin the unwelcome scrutiny of the Powers-that-be. Piskor’s explanations are short, not too complicated to follow, and easily digestible to the non-technical reader.

Wizzywig is a pretty good showcase of how a cartoonist maintains narrative momentum even when the characters are engaged in fairly mundane tasks. Like Chester Brown in Louis Riel, Piskor mostly sticks to the highly readable 6-panel grid layout. Characters in conversation or deep in thought are often shown walking from place to place. Or drawn in different poses and shifting perspectives if they’re merely sitting. Piskor’s eye for gritty detail is quite efficient in conveying setting and mood, but it’s his gift for caricature that stands out. No one's physical features are flattered, no matter however attractive. People often seem to possess odd proportions or carry themselves with terrible body posture. Most of them have big noses, sallow skin, shaggy hair, beady eyes. In contrast, Kevin’s impossibly poofy hair and pupiless eyes (again recalling Riel and Little Orphan Annie) suggests a potent mixture of innocence and craftiness.

At first glance, Kevin would appear to be the stereotypical nerdy kid who’s a whiz with computers, but has no friends or can’t get laid. But he’s an orphan living with a grandmother who’s incapable of providing him with enough adult supervision, or dole out the kind of practical advice on how to deal with school bullies. Kevin’s hacking doesn’t just arise from boredom or intellectual curiosity, but also from an impulse to strike back at his oppressors. Hacking becomes a non-physical form of asymmetrical warfare. The irony is that for all his social awkwardness, Kevin becomes particularly adept at what the industry calls “social engineering,” manipulating the behavior of other people to obtain information and get them to do what he wants. But his cunning also belies a deep naivete that leads to his eventual undoing. An early sign of things to come is when Kevin illegally resells gaming software, but as a joke inserts a bit of extra code into the program which will display the message “Boingthump owns your soul, sucka!” after 100 plays. Unfortunately this renders the game unplayable, and Kevin earns the ire of local gamers. More ominously, the code’s ability to infect whatever system the game’s installed into also gains media attention, and the name Boingthump becomes associated with computer viruses.

Kevin becomes a fugitive from the law around the halfway point, living a day-to-day nomadic existence. It turns out that the resourcefulness he’s displayed are particularly useful to life on the run. Much of this part of the book is still spent on educating the reader about various hacks: how to assume a false identity, find temp work, and not draw attention to oneself. Kevin runs a number of hustles just to stay alive. One particular scheme involves rigging numerous radio contests and recruiting women to claim the prize, usually taking the cash items for himself. His social engineering takes on an even more mercenary overtone, and Kevin’s portrayal becomes somewhat dehumanized as a result.

This part of the comic is where Piskor’s satire is at full force. The mainstream media’s treatment of hackers is embodied by a muckraking television journalist whose thick mustache and ludicrous combover makes him look like an older, evil version of Kevin. His reports on Kevin’s alleged crimes become increasingly sensationalized, with both the FBI and the Ma Bell only too happy to participate in the vilification process. Winston becomes the sole voice of reason in this climate of media-induced paranoia.

A side effect of this shift in tone is that Kevin becomes more a symbol of systematic injustice than a fully fleshed out individual. The earlier part of the book helped establish him as a sympathetic, if flawed human being. But his character development stalls as he becomes a fugitive, and later a prisoner. It becomes less about Kevin himself than his mistreatment at the hands of his captors. This saps the story’s intended emotional impact when Kevin’s grim experiences are connected to the wider world and latter day whistleblowers, such as Pfc. Bradley Manning and Wikileaks. It’s the most glaring weakness in a highly ambitious work which actually has something relevant to say about the present-day terrifying state of American politics.

3/26/2016

The Sculptor

By Scott McCloud

The Sculptor reminded me of that final bit from the 1984 film Amadeus when the aging composer Antonio Salieri realizes that he will never be remembered as anything more than another humdrum talent. So he declares himself the patron saint of mediocrity and absolves everyone around him of their own unremarkable qualities. Scott McCloud seems to be engaging in a somewhat similar act in this tortured, just shy of 500 pages, meditation on the nature of art, fame, and his own place in the comics pantheon. Not that McCloud makes any direct reference to himself in the story. His main hero David Smith is a failed sculptor, the running gag being that he shares his name with a real-life famous sculptor and dozens of anonymous people living in New York city. But David expresses some very definite ideas about art that will be recognizable to readers of McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Since that book’s publication, McCloud has acquired a reputation for being a notable comics theorist. But The Sculptor marks a much-heralded return to professional fiction writing after more than a decade’s absence, not to mention a test case for McCloud to put his own theories into practice. Dave himself starts out in a creative rut, and spends much of the book fighting his inner demons, which are an emotionally crippling blend of self-loathing and uncompromising perfectionism.

David is sort of an angrier, older version of Jenny Weaver from Zot! Despite being a reasonably good-looking guy, he’s too much of a social misfit to make friends, let alone get a girl to go out with him. More regrettably for him, he's burned almost all of his bridges to the highly competitive New York art scene. As he’s wallowing in self-pity, David receives a visitation from Death itself in the form of favorite uncle Harry. He’s then offered two options: Live a long and happy life in total obscurity, or make his mark on the world in the next 200 days before dying. When David chooses the latter, Harry imbues him with a superpower which will make it easy to mold any material into any shape or form - a useful skill for a sculptor.

Unfortunately, this is where the story begins to unravel a bit. But let’s first talk about the book’s virtues. McCloud has had a lot of time to hone his craft. Though not a particularly strong figure artist, here he doesn’t shrink from the arduous task of portraying dozens of very different individuals. And the results pay off. Even secondary and background characters feel well-thought out. And for a story set in New York, McCloud does a great job in capturing the city’s crowded conditions and diverse settings. The dark blue duotone palette combined with his scratchy linework produces a certain gritty, timeless appeal to the great metropolis. And his choice of viewing his characters from above in many panels conveys the imposing scale of the city’s architecture.

And the book is an engrossing page turner. The 200-day time limit creates plenty of tension to keep the reader guessing as to whether David will be able to sculpt anything memorable before the deadline, or whether he’ll be able to find a way out of his Faustian bargain. The Sculptor becomes increasingly cinematic as McCloud employs every panel-to-panel transition technique and nonlinear narrative device he’s outlined in the past to manipulate the flow of time within the story.

But McCloud has a habit of trading in archetypes that prevents him from shaping more believable characters. As a mouthpiece for McCloud’s aesthetic philosophy, it’s a laudable choice that David starts out as such an unsympathetic individual. His tendency to view the world from the vantage of moral absolutes and his initial complaint that he doesn’t have the chops to translate his vision into real art will be all too familiar to anyone who's hung around in an art school setting. There’s just a certain rigidity in execution that doesn’t allow McCloud to develop his character in unexpected ways or to acquire a more nuanced world view. At one point, David becomes a guerrilla artist. But this doesn’t mark any greater engagement with anyone outside of his small circle, or an increase in social awareness. He’s essentially still the same mopey individual, only now he’s defacing public property. This makes the book’s cheaply melodramatic conclusion kind of irritating. Even if David’s final artistic statement isn’t supposed to be a great masterpiece (which it clearly isn’t), does he still have to be so obnoxious about it?

Exacerbating David’s insufferable high mindedness is that for a college trained New York artist, he’s kind of crappy at what he does. That’s because his works look less like what a mediocre artist would produce than a cartoonist’s half-assed ideas about sculpture. For all their superficial similarities to abstract expressionism, they’re too pictorial, too tied up to a specific narrative, with not enough thought about their 3D qualities. A snooty critic compares them to a Polynesian gift shop. I’d say David’s sculptures have more in common with the PVC statues and action figures sold in comic conventions than the works found in an obscure student art gallery. This highlights McCloud’s artistic limitations. His style doesn’t quite succeed in projecting that sense of mass and volume needed to properly portray on the page David’s chosen medium.

The Sculptor actually devotes very little of its 500 pages to David’s creative process, and more to the love story between him and the enigmatic Meg. in my review of Zot! I noted how Zot was largely devoid of an inner life. His main job was to pull Jenny out of her misery. This is exactly the same with Meg and David. He first meets her playing an angel in a public performance piece, and she quickly becomes his muse. Meg’s so much of a savior figure that she even initiates David into certain mysteries of sex and how to relate to an actual functioning adult. Yeesh! To his credit, McCloud doesn’t make Meg half as ebullient as Zot. But his attempts to make her a more rounded personality are clunky in their delivery, particularly the introduction of her bipolar disorder. It still fails to impart Meg with much individual agency, let alone a complex inner life. So it turns into just another thing David has to deal with and work through on his way to making his deadline.

As for the art market David desperately wants to become a part of while constantly throwing shade at it, many of the attacks he levels at it are pretty familiar: Its disconnect from the rest of the world. The fixation on celebrity. A concern for economic value that overides artistic merit. But there’s something about the dogmatic proscription about what defines art combined with the book’s penchant for sentimental portrayal that comes across as immensely self-indulgent. And that ultimately ends up reinforcing the system it critiques.

The Sculptor reminded me of that final bit from the 1984 film Amadeus when the aging composer Antonio Salieri realizes that he will never be remembered as anything more than another humdrum talent. So he declares himself the patron saint of mediocrity and absolves everyone around him of their own unremarkable qualities. Scott McCloud seems to be engaging in a somewhat similar act in this tortured, just shy of 500 pages, meditation on the nature of art, fame, and his own place in the comics pantheon. Not that McCloud makes any direct reference to himself in the story. His main hero David Smith is a failed sculptor, the running gag being that he shares his name with a real-life famous sculptor and dozens of anonymous people living in New York city. But David expresses some very definite ideas about art that will be recognizable to readers of McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Since that book’s publication, McCloud has acquired a reputation for being a notable comics theorist. But The Sculptor marks a much-heralded return to professional fiction writing after more than a decade’s absence, not to mention a test case for McCloud to put his own theories into practice. Dave himself starts out in a creative rut, and spends much of the book fighting his inner demons, which are an emotionally crippling blend of self-loathing and uncompromising perfectionism.

David is sort of an angrier, older version of Jenny Weaver from Zot! Despite being a reasonably good-looking guy, he’s too much of a social misfit to make friends, let alone get a girl to go out with him. More regrettably for him, he's burned almost all of his bridges to the highly competitive New York art scene. As he’s wallowing in self-pity, David receives a visitation from Death itself in the form of favorite uncle Harry. He’s then offered two options: Live a long and happy life in total obscurity, or make his mark on the world in the next 200 days before dying. When David chooses the latter, Harry imbues him with a superpower which will make it easy to mold any material into any shape or form - a useful skill for a sculptor.

Unfortunately, this is where the story begins to unravel a bit. But let’s first talk about the book’s virtues. McCloud has had a lot of time to hone his craft. Though not a particularly strong figure artist, here he doesn’t shrink from the arduous task of portraying dozens of very different individuals. And the results pay off. Even secondary and background characters feel well-thought out. And for a story set in New York, McCloud does a great job in capturing the city’s crowded conditions and diverse settings. The dark blue duotone palette combined with his scratchy linework produces a certain gritty, timeless appeal to the great metropolis. And his choice of viewing his characters from above in many panels conveys the imposing scale of the city’s architecture.

And the book is an engrossing page turner. The 200-day time limit creates plenty of tension to keep the reader guessing as to whether David will be able to sculpt anything memorable before the deadline, or whether he’ll be able to find a way out of his Faustian bargain. The Sculptor becomes increasingly cinematic as McCloud employs every panel-to-panel transition technique and nonlinear narrative device he’s outlined in the past to manipulate the flow of time within the story.

But McCloud has a habit of trading in archetypes that prevents him from shaping more believable characters. As a mouthpiece for McCloud’s aesthetic philosophy, it’s a laudable choice that David starts out as such an unsympathetic individual. His tendency to view the world from the vantage of moral absolutes and his initial complaint that he doesn’t have the chops to translate his vision into real art will be all too familiar to anyone who's hung around in an art school setting. There’s just a certain rigidity in execution that doesn’t allow McCloud to develop his character in unexpected ways or to acquire a more nuanced world view. At one point, David becomes a guerrilla artist. But this doesn’t mark any greater engagement with anyone outside of his small circle, or an increase in social awareness. He’s essentially still the same mopey individual, only now he’s defacing public property. This makes the book’s cheaply melodramatic conclusion kind of irritating. Even if David’s final artistic statement isn’t supposed to be a great masterpiece (which it clearly isn’t), does he still have to be so obnoxious about it?

Exacerbating David’s insufferable high mindedness is that for a college trained New York artist, he’s kind of crappy at what he does. That’s because his works look less like what a mediocre artist would produce than a cartoonist’s half-assed ideas about sculpture. For all their superficial similarities to abstract expressionism, they’re too pictorial, too tied up to a specific narrative, with not enough thought about their 3D qualities. A snooty critic compares them to a Polynesian gift shop. I’d say David’s sculptures have more in common with the PVC statues and action figures sold in comic conventions than the works found in an obscure student art gallery. This highlights McCloud’s artistic limitations. His style doesn’t quite succeed in projecting that sense of mass and volume needed to properly portray on the page David’s chosen medium.

The Sculptor actually devotes very little of its 500 pages to David’s creative process, and more to the love story between him and the enigmatic Meg. in my review of Zot! I noted how Zot was largely devoid of an inner life. His main job was to pull Jenny out of her misery. This is exactly the same with Meg and David. He first meets her playing an angel in a public performance piece, and she quickly becomes his muse. Meg’s so much of a savior figure that she even initiates David into certain mysteries of sex and how to relate to an actual functioning adult. Yeesh! To his credit, McCloud doesn’t make Meg half as ebullient as Zot. But his attempts to make her a more rounded personality are clunky in their delivery, particularly the introduction of her bipolar disorder. It still fails to impart Meg with much individual agency, let alone a complex inner life. So it turns into just another thing David has to deal with and work through on his way to making his deadline.

As for the art market David desperately wants to become a part of while constantly throwing shade at it, many of the attacks he levels at it are pretty familiar: Its disconnect from the rest of the world. The fixation on celebrity. A concern for economic value that overides artistic merit. But there’s something about the dogmatic proscription about what defines art combined with the book’s penchant for sentimental portrayal that comes across as immensely self-indulgent. And that ultimately ends up reinforcing the system it critiques.

2/25/2016

Cartoon: The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham

Go to: OSU Libraries, by Sterling South & David Wigransky. Posted by Carol Tilley & Caitlin McGurk (via Tom Spurgeon)

11/14/2015

Love from the Shadows

by Gilbert Hernandez

cover: Steve Martinez

design: Alexa Koenings

A meta-fictional conceit of Gilbert Hernandez’s standalone “Fritz” stories is that Rosalba “Fritz” Martinez, one of the more popular recurring characters from his Palomar series, once starred in a bunch of godawful B-movies. By adapting these movies into a growing collection of graphic novels, Gilbert can capitalize on the pre-existing appeal of this tragic, top-heavy bombshell of a figure while working on the pretense that these are new characters operating under completely different circumstances. Fritz has long been notorious for her outrageous combination of high intelligence, a voluptuous physique, light skin, voracious sexual appetite, and speaking with a “high soft lisp”, which has been alternately treated by the people around her as either endearing or deeply annoying. But she’s also been a victim of abuse at the hands of her past sexual partners, numbing the pain with bouts of heavy drinking. Love from the Shadows exploits many of those traits in Fritz’s most bravura performance and a perverse, violent, bizarre tale. I can’t really say if this is a good comic, let alone if the movie it’s pretending to be based on is worth watching. But it is strangely compelling.

And as an apparent rebuke to those fans who’ve dismissed Gilbert for his particular propensity for drawing buxom women, the graphic novel’s cover is his most confrontational yet. Painted by Steve Martinez, the pulpy, lurid quality of the bikini-clad pin-up lounging on a beach next to the ominous shadow of an unseen individual hovering behind her promises to supply all the cheap thrills expected of a clunky matinee movie, not to mention satisfy the reader’s prurient interests. It probably helps catch the eye of the prospective customer given how it's largely unconnected to the events within the book itself.

The story within certainly contains copious amounts of violence and sex, though they feel grafted on top of a grim and elliptical psychological drama. It begins with a forlorn Fritz standing inside an empty house. She slowly wanders from room to room, examines her breasts in front of a mirror, calls her dad on the phone, only to be cruelly rejected by him. It’s a simple action sequence drawn with Gilbert’s usual black and white minimalism. But one that’s fraught with emotional weight due to his mastery of composition, time, facial expressions and body language. Every line exudes both anguish and desperation from the character. But the scene also conveys just how Fritz’s own sensuality seems to weigh heavily on her entire existence. It’s practically impossible to distinguish her history from the character she’s now supposably playing.

Fritz responds to her father’s rejection by calling on an attractive young man. But as they walk to her house, she’s accosted by a group of mysterious, visor-wearing individuals called “monitors”. “How come you look like that? How come your skin is like that? How come you talk like that?” they ask while blithely invading her personal space. After they reach her house, Fritz engages her impassive partner in vigorous love-making. But as she tries to engage him in conversation, he quietly leaves when she goes to the kitchen to prepare a meal for him.

What happens afterward is difficult to summarize and makes little sense except as some kind of fevered dream. Fritz spots the monitors outside her house and flees to the basement, only to enter a mysterious cave. when she emerges on the other side, she’s somehow acquired a new identity (complete with new hair color) as a woman named Dolores. Actually, it’s even more complicated as Fritz also plays Dolores’ brother Sonny and their estranged father, who happens to be a famous novelist. At one point Dolores becomes involved with a trio of spiritualist hucksters, Sonny has a sex change operation and impersonates Dolores. A ghost delivers a prophecy which Dolores fulfills in the most brutal manner. There are two recurring motifs: the monitors continue to hound her like a creepy Greek chorus. And the cave continues to lure characters in with promises of secret knowledge and in some cases, drive them insane. Gilbert draws it as an inky black abyss. An absolute void. Could any other metaphor be so infuriatingly on-the-nose while being so open to interpretation? Death, the Underworld, Nirvana, the Subconscious Mind, Wisdom, the Wellspring of Creativity, the Primordial Universe, the Heart of Darkness. Or maybe it’s just a game Gilbert is playing with the reader to see what they can come up with?

If so, it is an abstruse game. Gilbert is a prodigious storyteller whose powers have diminished very little. But he’s made a sharp left turn away from the humanism and diverse cast of characters found in his Palomar stories towards something a little more austere, baffling, less compassionate.

cover: Steve Martinez

design: Alexa Koenings

A meta-fictional conceit of Gilbert Hernandez’s standalone “Fritz” stories is that Rosalba “Fritz” Martinez, one of the more popular recurring characters from his Palomar series, once starred in a bunch of godawful B-movies. By adapting these movies into a growing collection of graphic novels, Gilbert can capitalize on the pre-existing appeal of this tragic, top-heavy bombshell of a figure while working on the pretense that these are new characters operating under completely different circumstances. Fritz has long been notorious for her outrageous combination of high intelligence, a voluptuous physique, light skin, voracious sexual appetite, and speaking with a “high soft lisp”, which has been alternately treated by the people around her as either endearing or deeply annoying. But she’s also been a victim of abuse at the hands of her past sexual partners, numbing the pain with bouts of heavy drinking. Love from the Shadows exploits many of those traits in Fritz’s most bravura performance and a perverse, violent, bizarre tale. I can’t really say if this is a good comic, let alone if the movie it’s pretending to be based on is worth watching. But it is strangely compelling.

And as an apparent rebuke to those fans who’ve dismissed Gilbert for his particular propensity for drawing buxom women, the graphic novel’s cover is his most confrontational yet. Painted by Steve Martinez, the pulpy, lurid quality of the bikini-clad pin-up lounging on a beach next to the ominous shadow of an unseen individual hovering behind her promises to supply all the cheap thrills expected of a clunky matinee movie, not to mention satisfy the reader’s prurient interests. It probably helps catch the eye of the prospective customer given how it's largely unconnected to the events within the book itself.

The story within certainly contains copious amounts of violence and sex, though they feel grafted on top of a grim and elliptical psychological drama. It begins with a forlorn Fritz standing inside an empty house. She slowly wanders from room to room, examines her breasts in front of a mirror, calls her dad on the phone, only to be cruelly rejected by him. It’s a simple action sequence drawn with Gilbert’s usual black and white minimalism. But one that’s fraught with emotional weight due to his mastery of composition, time, facial expressions and body language. Every line exudes both anguish and desperation from the character. But the scene also conveys just how Fritz’s own sensuality seems to weigh heavily on her entire existence. It’s practically impossible to distinguish her history from the character she’s now supposably playing.

Fritz responds to her father’s rejection by calling on an attractive young man. But as they walk to her house, she’s accosted by a group of mysterious, visor-wearing individuals called “monitors”. “How come you look like that? How come your skin is like that? How come you talk like that?” they ask while blithely invading her personal space. After they reach her house, Fritz engages her impassive partner in vigorous love-making. But as she tries to engage him in conversation, he quietly leaves when she goes to the kitchen to prepare a meal for him.

What happens afterward is difficult to summarize and makes little sense except as some kind of fevered dream. Fritz spots the monitors outside her house and flees to the basement, only to enter a mysterious cave. when she emerges on the other side, she’s somehow acquired a new identity (complete with new hair color) as a woman named Dolores. Actually, it’s even more complicated as Fritz also plays Dolores’ brother Sonny and their estranged father, who happens to be a famous novelist. At one point Dolores becomes involved with a trio of spiritualist hucksters, Sonny has a sex change operation and impersonates Dolores. A ghost delivers a prophecy which Dolores fulfills in the most brutal manner. There are two recurring motifs: the monitors continue to hound her like a creepy Greek chorus. And the cave continues to lure characters in with promises of secret knowledge and in some cases, drive them insane. Gilbert draws it as an inky black abyss. An absolute void. Could any other metaphor be so infuriatingly on-the-nose while being so open to interpretation? Death, the Underworld, Nirvana, the Subconscious Mind, Wisdom, the Wellspring of Creativity, the Primordial Universe, the Heart of Darkness. Or maybe it’s just a game Gilbert is playing with the reader to see what they can come up with?

If so, it is an abstruse game. Gilbert is a prodigious storyteller whose powers have diminished very little. But he’s made a sharp left turn away from the humanism and diverse cast of characters found in his Palomar stories towards something a little more austere, baffling, less compassionate.

11/07/2015

The Ticking

by Renée French

As with any comic created by Renée French, The Ticking’s strength is found in her inimitable visuals. French draws these flat, super-deformed cartoon characters, but renders them not with solid black lines but with soft graphite. The resulting three-dimensional quality of the art makes their presence on the page ambiguously disturbing, like a barely remembered vision or nightmare. There’s just a slight hint of the “uncanny valley”, which actually helps enhance the strangeness. But this isn’t done in the service of satire or social commentary. French’s gaze is trained inward, and her sympathies clearly lie with the ugly and the disfigured.

The preciousness of the art is further enhanced by the stark presentation. Most pages contain one or two square panels, stacked vertically. Any dialogue is displayed in handwritten script below each panel. This organic minimalism is exquisite, but very effective, and makes for a quick read. It lends the simple story within a modern fairy tale quality.

The book starts shockingly enough with the birth of its hero Edison Steelhead, a baby possessing a grotesquely large head with beady eyes so far apart they’re located at the side rather than the front of his face. His mother dies on the kitchen floor from the act of giving birth, and his grieving father Calvin raises Edison in isolation on a remote island lighthouse. While this may seem like Calvin is protecting from the outside world, the reader is clued in early that it’s as much an expression of self-loathing as it is of loving concern. Calvin blames himself for his son’s physical imperfections.

Raised in such a nurturing but stifling environment, Edison learns to cope by observing everything and drawing in his sketchbook. He catalogs the smallest details of his world with diagrammatic line drawings, which French reproduces as one page spreads. They serve as important story beats, pausing the narrative and letting the reader into Edison’s developing mind. As his imagination and curiosity grow, Edison slowly comes to chafe under his father’s tight control. When Calvin unexpectedly brings home a little sister named Patrice, a chimpanzee wearing a dress, Edison begins to realize the need to explore the wider world on his own terms.