|

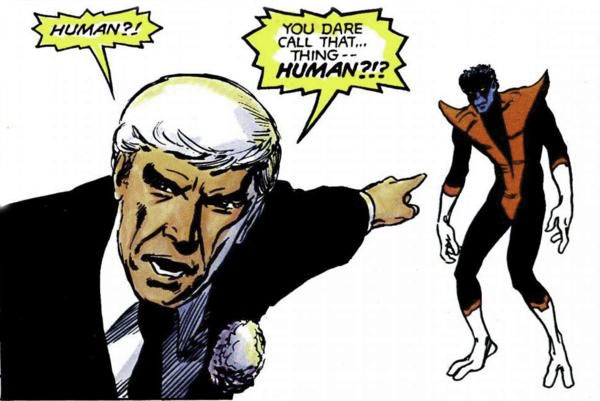

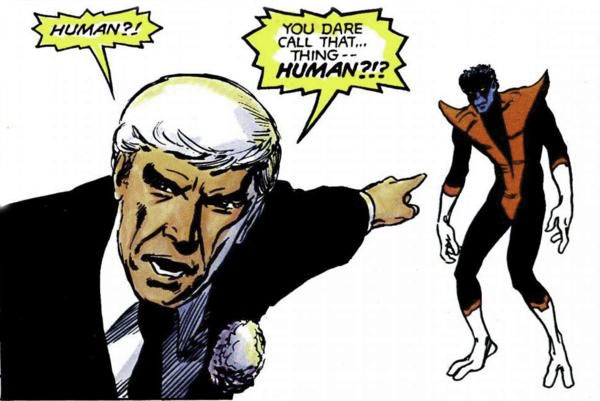

Marvel Graphic Novel #5: God Loves, Man Kills, 1982, by Chris Claremont,

Brent Eric Anderson, et. al. |

Comics’ default position on diversity seems to be one of avoidance – a position that’s perfectly summed up by the Scarlet Witch’s memorable phrase, ‘No more mutants’. Those three words might also suggest the best way forward; let’s stop talking in metaphors and put the actual minorities in comics, to tell their own stories.

- Andrew Wheeler

Andrew Wheeler has written an interesting series of columns in which he tackles how mainstream comics (i.e.

Marvel and

DC) have attempted to deal with the issues of

racial prejudice,

sexual inequality, and

dubious minority representations. It's a informative survey of the seemingly arbitrary and incoherent editorial decisions that publishers make in order to preserve continuity. These choices inevitably induce a fair degree of defensiveness amongst fans. But that's a whole other topic for discussion. For now, "No more mutants" sentiment is a good place to start.

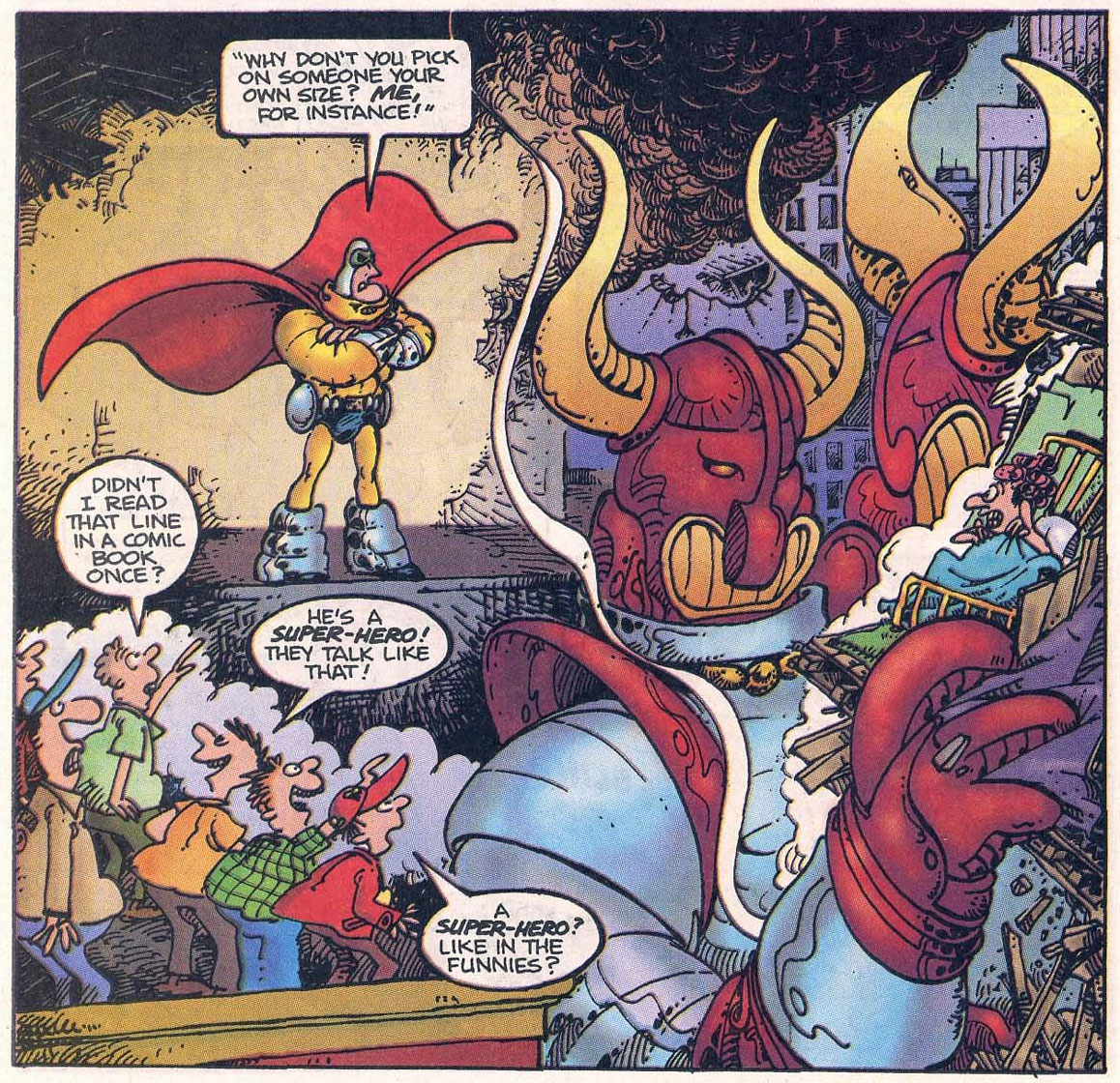

I'm not closely following the events within the X-titles that gave rise to that phrase, so I can't really say how this latest mutant massacre differs from other past massacres. But Andrew does briefly touch on one thing about the

X-Men that's bugged me for a long time now - While the mutants are clearly an oppressed minority within the context of the Marvel Universe, they are an incomplete metaphor for this thing in the real world called "race". The

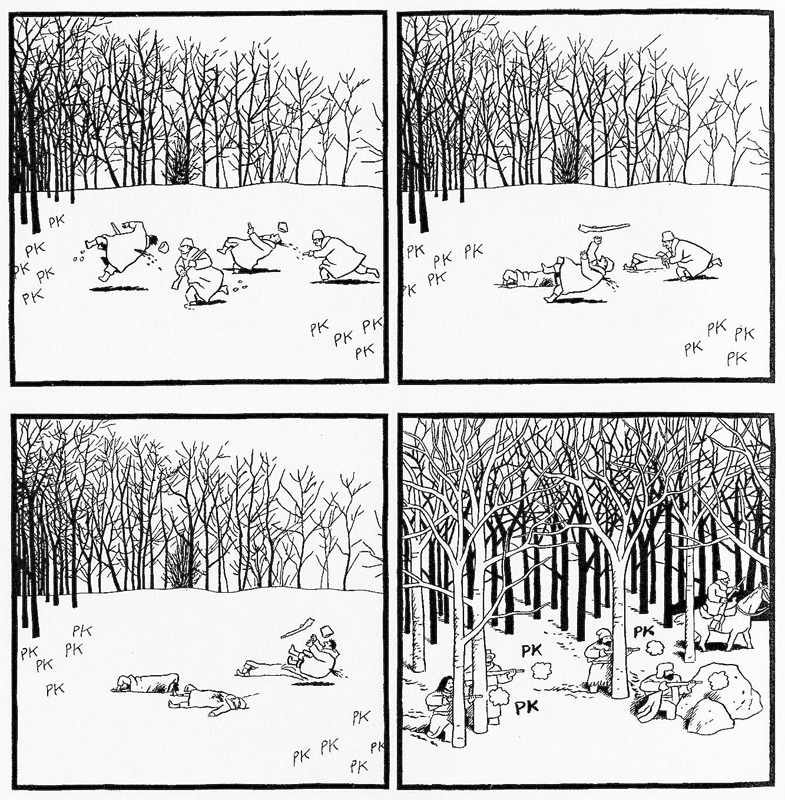

X-Men comics traditionally viewed race from a mainly negative perspective, which was one of discrimination and resentment. Mutants were either hunted-down and rounded-up, recalling genocidal campaigns of the past. Or they were lynched, echoing similar practices from American history.

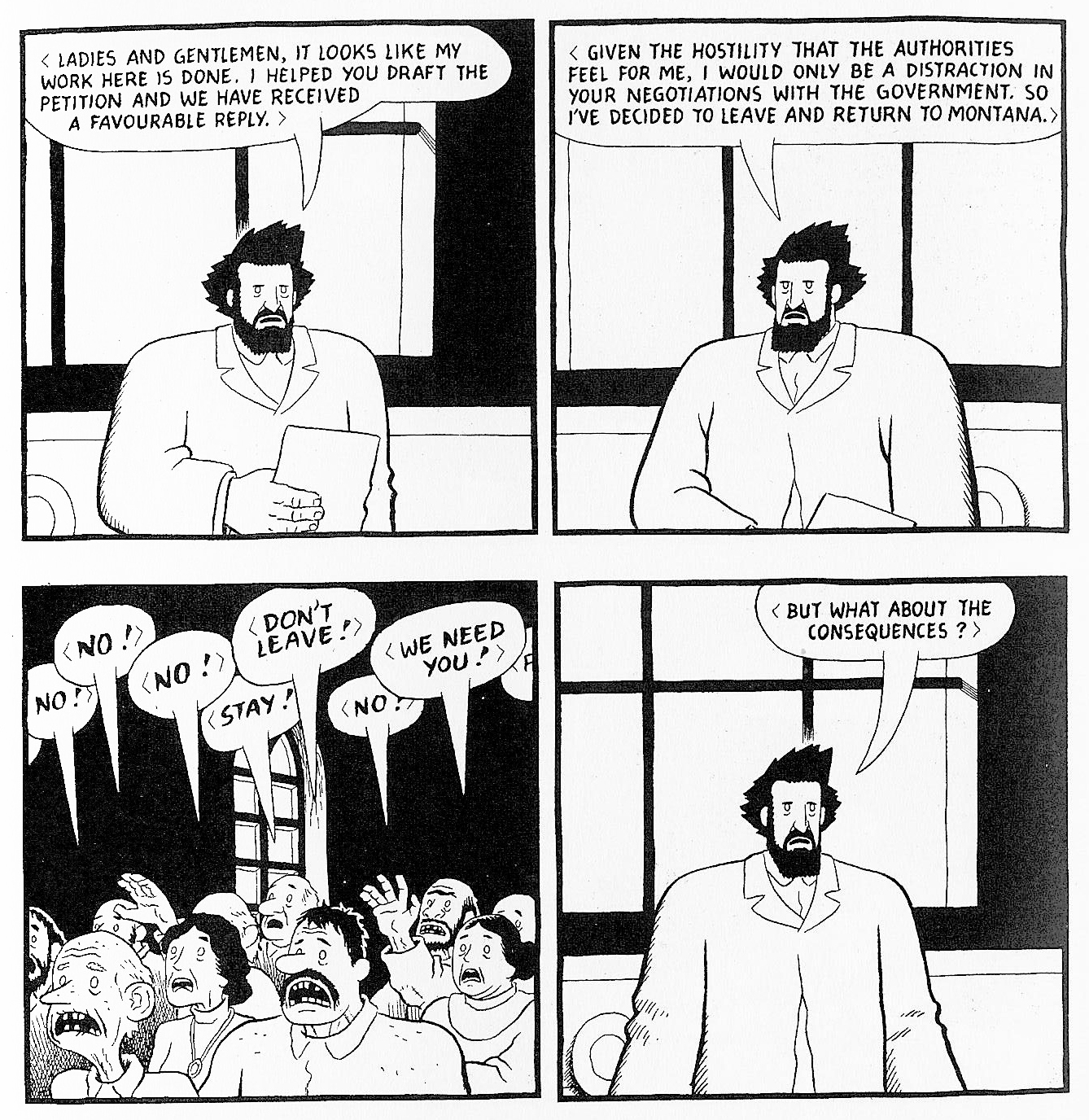

What was missing in these portrayals was a

preestablished culture. If people are going to insist that mutants are a metaphor for real-world racial politics, then the lack of an

ancient tradition is a pretty big omission. The mutants began as a blank slate. As minorities go, they didn't have their own archaic customs, norms, myths, art or science. They didn't have their own

alternate history that was being suppressed by a more powerful group. As a social classification, they're still

brand new. They started out in the comic pages being vaguely defined by a popular misinterpretation of science (the X-gene and the effects of radiation), and were unable to counteract it with any kind of long-established, internally generated, traditional identity. The oft-repeated claim that mutants are the next step in human evolution puts them light years apart from the ground-level concerns of real ethnic groups who face discrimination because they are viewed as inferior and backward. And if I recall correctly, the original members of the X-Men were

white teenagers born and raised within mainstream American culture. They were simply denied by their own society's widespread prejudice from openly integrating into it. So it's no surprise that they were a miserable lot (That and living in a never-ending soap opera). That's not the same as people being feared, hated, or treated with casual condescension because they openly identify with an altogether

alien (e.g. non-European) community or ancestry. If the X-Men were ever a suitable analog for any particular group of people, it would be for the series'

geeky fanbase who were searching for the perfect comic book vehicle for their own adolescent frustrations.

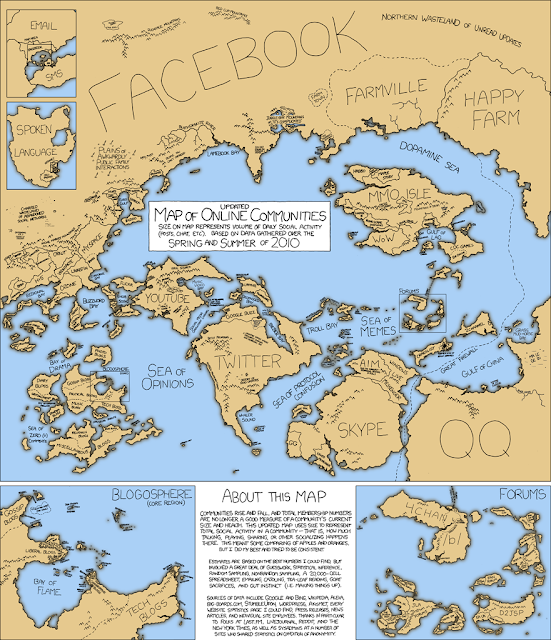

Now, it's not unrealistic to expect any minority group being ostracized for whatever reasons (age, gender, sexual orientation, profession, hobbies, skills, unique abilities etc.) to form their own counter-culture at some point. Marvel's mutant population should be no different in this regard. There should be mutant artists, musicians, writers, designers and other creative types. There should be respected intellectual figures along with vapid celebrities. If there's already a school for mutants, where are the museums, galleries, theatres, clubs, restaurants, and other institutions which are, at the very least, sensitive to mutant perspectives? And if there's a mutant counter-culture, wouldn't this inevitably spill over to the rest of the Marvel universe? A couple of writers have tried to explore this area. The tentative beginnings within the series could arguably be traced back to arch-villain

Magneto's separatist ideas.

Mike Allred put mutants under the media spotlight when he took over

X-Force. But the process was only accelerated to its logical conclusion when rebellious teenagers started worshipping their own mutant idols during

Grant Morrison's run on

New X-Men. I guess that's all being undone now in the name of bringing the X-Men back to their secretive roots. As Andrew quotes editor-in-chief

Joe Quesada:

"...we ended up with a mutant island where there were over six million of them, and every time you’d turn a page, you’d see a mutant on every corner. We even had ‘Mutant Town’. So, one of the things that we wanted to do was put the genie back in the bottle.”

Taken on it's own terms, what's being voiced unfortunately sounds too much like: God forbid if minorities of any kind could be spotted openly walking down the street of every major city, living wherever they choose, or be allowed to congregate at their own preferred hangouts. Especially if it messes with the superhero universe's precious status quo.

|

| New X-Men #135, 2003, by Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, et. al. |

I'm not necessarily implying that this editorial decision is being consciously motivated by racism or sexism, or any other form of intolerance. But it does highlight how working with decades-old legacy characters, while being beholden to accepted modes of expression, can sometimes make it harder for creators and readers who want to explore new and possibly fertile ground. Creative change is being proscribed by genre convention, fastidious fandom, or protective intellectual property owners.

Or perhaps Marvel's merry band of misfits are just no longer the optimal vehicle to drive a relevant discussion on race and diversity, if they were ever one at all.