By Fabien Vehlmann and Kerascoët (Marie Pommepuy and Sébastien Cosset)

Translated by Helge Dascher.

Beautiful Darkness is sort of a cruel joke played on readers who believe in the power of fairy tales. Or to be more precise the kind of fairy tales parents usually tell their kids when they want to assure them there is a higher power who punishes the wicked and rewards the innocent. In the later graphic novel Beauty (which was also drawn by Kerascoët in a completely different visual style), there are supernatural forces who interfere in the lives of mere mortals. No such beings exists here. Whatever magic is manifested is entirely earthbound and found only within human beings. But what happens when the moral order that guides them is dissolved and humanity’s constituent fragments are left to fend for themselves? BD explores in miniature what happens during the slow decay of civilized order and logic into the uncaring but much grander patterns of the natural world.

If this sounds very grim, the book’s narrative approach is disarmingly seductive. The story begins looking very much like a conventional children’s book illustrated in lush watercolors. A spritely blonde woman with large black eyes named Aurora is living a fantasy life as a princess. She’s having tea with her princely, redheaded beau Hector when their world suddenly begins to liquefy around them. As giant slimy globs fall, the denizens of this kingdom fight their way through the purification until they emerge into the open air. The reader is then made aware of the story’s first major twist: that their grand home is the body of a young girl who has died in the woods under mysterious circumstances.

The cause for the girl’s sudden death is never fully revealed, through an ominous full-sized adult figure keeps hovering in the background and will come to play an important role later on. Led by the irrepressible Aurora, the sprites attempt to rebuild their world around the girl’s rotting corpse like survivors eking out a living near the ruins of a crumbling city. The entire project starts out in good spirits, and everyone appears to be more-or-less cooperating with each other. But cracks soon appear as each character starts pursuing their own competing agendas.

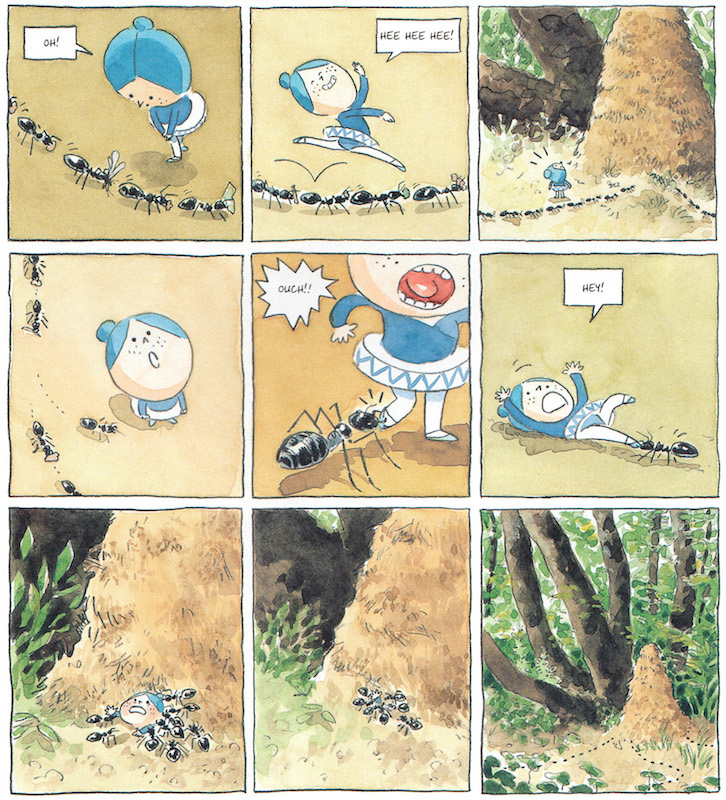

BD’s narrative possesses a deceptive episodic structure. Everything starts out with an air of naive optimism. The incidents are mostly comical and seemingly inconsequential. But as the mistakes accrue, each mishap and misadventure pulls the sprites inexorably towards some terrible doom. Halfway through, there’s a growing sense that events have reached a point of no return. The sprites increasingly turn on each other and blood is spilled on a more regular basis. What starts out as an impromptu society has broken up into factions.

What enhances that dread is the cartoonishly cute manner of the sprites. This gives them a sense of vulnerability which stands in stark contrast to the humans and the natural setting, which are drawn with detailed realism. This visual contrast underlies a difference in scale. The magical beings are dwarfed by their surroundings, making them appear to be constantly in danger from attacks from the local fauna and exposure to the elements. But that scale mostly emphasizes the overall indifference that greets the sprites. For the most part, nature simply ignores them. And that kind of cosmic insignificance is so much worse.

The cartoony style is also key to making the sprites into instantly recognizable archetypes. There’s the shy wallflower, the manipulative queen bee, the eager sidekick, the self-sufficient loner, the squabbling triplets, the cutie doll, etc. Hector is a foppish aristocrat with little depth to him. As they all emerged from a dead girl’s corpse, it’s easy enough to suppose that they might embody different facets of her psyche. If this is the case, then Aurora is the heart of the girl. Sweet and trusting, the image of unassuming feminine beauty, she’s the only person who seems emotionally invested in keeping everyone together. And her reaction to her own failures makes for some of the book’s most unsettling passages.

Given BD’s premise and increasingly gloomy tone, I’m not entirely surprised that the book has drawn comparisons with Lord of the Flies. Both map out how altruism eventually loses out to the Will to Power. It’s certainly possible to see in BD’s subversion of fantasy imagery a nihilistic critique of the illusory nature of morality and futility of civilized modernity. This could be the most accurate interpretation of the tale, given the creators’ cultural milieu.

But there’s something about the lovely portrayal of verdant nature that reminds me of the Sea of Corruption in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Just as humanity fights a losing battle against the world-spanning toxic forest, the sprites are slowly being consumed by the incomprehensibly vast woods. The story begins in spring and follows the imperceptible rhythm of nature’s seasonal changes. BD ends on a down note, during the depth of winter. But just as Nausicaä saw a vision of a world cleansed of man-made pollution, maybe there’s a new, beautiful spring beyond the last page of this book? Or maybe not.