|

| No Room at the Gotham Inn |

7/21/2008

7/14/2008

Manga's Future

I’m not sure that manga readers here are really manga readers and I would even go so far as to say that they’re not even comics readers. There’s a love for the medium, but only within the shojo or shonen genre. They love the anime, and honestly, while I was watching the Le Chevalier D’eon anime, I couldn’t help but thinking “this is cartoons. It’s for kids.”

- Kai-Ming Cha

I am outright terrified that the North American manga publishing industry is going to turn into a mirror of the superhero publishing industry; comprised of adult fans clamouring for vaguely more mature versions of children’s material, operating in a two-company system, growing steadily more insular and inaccessible to the world at large. I don’t think it has to happen, of course, and I’d like to think I’ve discussed a few of the ways in which it won’t, but there’re my fears. Hopefully they’re never realized.

- Christopher Butcher

Kai-Ming Cha is stating the obvious here, although it's something that tended to get lost in the early heated pro-manga vs. anti-manga debate - Most consumers of any form of entertainment have narrowly defined tastes. Only a minority of readers are ever going to possess a broad and deep love for the medium. It's a lot easier for fans to identify themselves in relation to a certain camp, like superheroes, manga, fantasy, or science fiction. I'm reminded of all the hype about how the Harry Potter series got kids to read again, as if reading those books would eventually lead them to seek out Steinbeck and Shakepeare.

His second point is also equally obvious - People's tastes change over time. The young readers who enjoy Naruto or Fruits Basket now are not necessarily going to like them when they become adults. This is one reason behind the arguments for a more diverse market: A wider selection of genres and styles attract a greater demographic range. However Kai overstates his case when he worries that the present generation of readers will outgrow manga, leaving only the next batch of incoming readers to take their place. How is the market's youthful bias different from other forms of entertainment? Most film and television is aimed at the lowest common denominator, so it doesn't surprise me that manga publishers market fantasies to a largely young audience. I don't see that changing in the foreseeable future. But one shouldn't underestimate the crossover appeal of some youth-targeted popular entertainment. So to me it's not at all a clear-cut case of manga readers only coming from a certain a juvenile age group.

Nevertheless the recent financial troubles of retail chain Borders Books and publisher Toykopop have shown that the previous period of spectacular uninterrupted growth has ended. The manga boom has gone on long enough that it can no longer be dismissed as a fad, but this also means that a generation has grown-up reading manga. This raises the question of what will happen to that audience. No doubt some will abandon the comics medium entirely. Some will continue to read manga or other comics on a casual basis, and others will become hardcore adult fans. If the manga market starts to hemorrhage readers and doesn't replenish them with sizable numbers of younger fans, then manga fandom will, as Christopher Butcher fears might happen, resemble the aging superhero fandom that made the direct market a dead end in the nineties before manga infused the western comics industry with a much needed dose of new readers. I'm inclined to believe that manga will continue to be mostly successful in attracting new readers, but Butcher is right in saying that publishers and retailers still need to get better at marketing to an adult audience. I'm inured to the crowds of gawky teenagers blocking my path when I wander the manga shelves of my local Borders, but they must deter a lot of would-be adult readers. There's still no real help for the uninitiated to differentiate between the different genres targeted to different audiences in the graphic novel sections of most bookstores. Further complicating the issue is that cultural differences can cause manga originally aimed at a younger Japanese audience to be repackaged as appropriate material for an adult readership, and vice-versa.

Looking at it from a wider perspective, manga is here to stay. Other countries have been exposed to manga and anime before the English-speaking world caught on, and even if the worst case scenario happens and Japanese comics market collapsed in America, it would continue to thrive elsewhere. Like it or not, manga is at the center of the comics world.

7/13/2008

7/12/2008

Glamourpuss #1

"...I want to do photorealism pictures of pretty girls, so that's I'm going to do. The words were an aterthought. Okay, let's stick with that. " - Dave Sim

Dave Sim isn't the first cartoonist who's wanted to spend time drawing pictures of attractive women, nor will he be the last. Not content with compiling his drawings into an art book, he's chosen to engage his audience in detailed discussion about his work. Hence we have a new series called Glamourpuss. This 1st issue contains Sim's attempts to draw his chosen subjects in the style of Alex Raymond, John Prentice, Al Williamson, Stan Drake and Neal Adams, accompanied by comics-style narrative text explaining the results of his efforts. The desire to document his autodidactic obession is combined with an almost equally strong need to instruct and inform the reader. He knows they'll only glance momentarily at each picture before moving on, so he insists they spend a bit more time marveling at the craft involved in order to draw like these old masters of the medium.

It's a curious project to say the least. Dave Sim is an accomplished comics artist - some would argue he's one of the industry's greatest living practitioners. So it's hard to ignore his retro choice of art style to impersonate from. The results are at first glance, very convincing. Sim uses as his reference various unnamed fashion magazine photos, which he draws in the photorealist manner. He also takes panels from the Rip Kirby comic strip out of their original context, redraws them, then juxtaposes them along with his fashion illustrations. Needless to say, the continuity between the pictures is nowhere near as seamless as in a more conventionally constructed comic. But then again Sim seems less interested in telling a story for story's sake than in educating the reader about a bit of comics history. His self-crticism reaches maniacal levels as he attempts to guess what lines to leave in, how to depict certain textures with a brush, or what areas to interpret as pure black.

The centerpiece of the book is a six page sequence entitled The Self-education of N'atashae. It's composed of a series of full page drawings of one fashion model, linked by heavy-handed narration detailing her thoughts and misguided attempts to achieve spiritual enlightenment. Sim is attempting to simultaneously do several things: He's trying to demonstrate the immense difficulty of constructing a story from disparate sources; Provide a kind of secret origin story for the comic; And he's poking fun at the vacuousness of the fashion industry as well as the shallowness of materialistic western consumer culture. Sim just can't help being didactic.

Glamourpuss is basically a hybrid product - Part black and white comic pamphlet, part illusrated essay, and part fashion magazine parody. Digressions about craft are interrupted by spoof articles and fake ads. While the shop talk will be of interest to history buffs and aspiring artists, the attempts at humor produce mixed results. Dim looking fashion models make an easy target, but Sim's jokes are a heavy blunt weapon he ungainly wields to make his point. One article titled Skanko's Dating Guide might remind people of Sim's past controversial statements.

It's not clear where all of this is headed. While the fashion drawings are beautifully rendered, they also reveal the underlying homogeneity of the source material. There's something cumulatively oppressive about the overall tone of the work that probably arises from the disjointed panels and text's attempts to impress its lessons on the reader. Sim's parody gets a bit tiresome by the end of the issue, but he intends to continue Glamourpuss for more that 20 issues. What more does he have to say? Then again, Dave Sim is the man who delivered on his promise that Cerebus would die, alone, unmourned and unloved after 300 issues. So I wouldn't be surprised if he has a master plan that will gradually reveal itself as the series unfolds.

7/07/2008

6/29/2008

Larry Gonick Has a Blog

From Raw Materials by Larry Gonick for the Discovery Channel website. I enjoyed his past strips for Discover Magazine. I'd like to see those compiled.

6/22/2008

Poster Design: Explore. Just Protect Yourself

Two posters illustrated by DC cover artist James Jean for a European NGO. I doubt I'll ever see these plastered around Brisbane or Manila. Link by Mark Frauenfelder.

Update:

James Jean explains the creative process involved in the creation of these poster designs in his blog.

Update:

James Jean explains the creative process involved in the creation of these poster designs in his blog.

6/19/2008

Curmudgeon

In the stories published in the period before the production of the American Splendor movie, Harvey Pekar admitted that he was desperate to sell-out to Hollywood. His living expenses had increased now that he had a foster daughter to take care of. And he finally wanted to retire from his file clerk day job. It seems almost bizarre, but at the time he was even considering an option which would star former SNL cast member Rob Schneider. Pekar finds out that selling-out isn't so easy as it looks. He also started to wonder a lot about his creative legacy. He identified himself with overlooked artists and creators, and probably thought he was going to die in obscurity. The film was eventually made, and won a couple of awards. But it's funny how much worrying about it ever getting made took up so much of his time.

6/15/2008

6/14/2008

Dororo Vol 1

Dororo is a minor work that Osamu Tezuka never got around to finishing. Neither as long-lived as the hugely popular ATOM or Black Jack, nor as ambitious as Adolf or Buddha. But even lesser Tezuka proves to be a very potent read. This was a man brimming with many mad ideas. Dororo may be formulaic entertainment. But it's very well executed formulaic entertainment.

Set during the chaotic Sengoku period, an ambitious warlord makes a faustian bargain with 48 demons to sacrifice his unborn first child in return for greater political power. The baby boy is born with 48 missing body parts. He is left to die from exposure, but is adopted by a kindly surgeon, who later equips him with various prosthetic substitutes (Not bad for a 15th century physician). The child, named Hyakkimaru, grows into an effective demon hunter hoping to kill the demons who stole his body parts, and restore his body. Early on he meets an orphaned street-smart kid named Dororo. They quickly establish an uneasy but friendly rapport, and he joins Hyakkimaru is his quest because he covets the sword blades he carries.

It's truly astonishing how much Tezuka can get away with. The book is filled with so much violence, gore, and nasty supernatural elements, yet feels so thoroughly upbeat. This is in part because Tezuka's art is just so awesome. His monsters and demons are both frightening enough to scare kids while weirdly eccentric enough to amuse older readers. The disfigured baby Hyakkimaru evokes both horror and sympathy for his condition. The adult version makes for a dynamic heroic figure - slashing enemies left and right with katanas hidden inside his prosthetic arms. Tezuka's virtuoso cartooning alone is worth paying the price for this book. Everything from the atmospheric backgrounds to the creature designs are drawn with the confidence of a master comfortable with his craft.

Hyakkimaru and Dororo are easy enough to empathize with. Both are victims of the violent era they live in, and both are looking for ways to rise above their humble beginnings and find personal redemption through hard work. In certain ways they're the template for many shonen heroes that would come afterward. The author's voice clearly sides with the commoners against the samurai class, who are treated as the root of all misery in the world. The protagonists themselves have a lot or reason to be resentful to the samurai class, while enjoying the freedom that comes from their rootless lifestyle.

The parts of the volume that don't deal with the characters back-story focus on episodic action-adventure. The first involves a frog monster/faced-shape tumor that has enslaved an entire village. The second is about a warrior forced to kill by a cursed sword. Tezuka doesn't shy away from presenting the carnage. In fact this book is a useful example of how he mixes serious drama with slapstick comedy, oftentimes in the same panel. By this time Tezuka had already developed an array of quirky comic techniques: characters breaking the fourth wall, cartoon self-portraits, anachronistic asides, and cameos by characters from other comics. Thankfully these gimmicks don't distract too much from the main story.

This isn't Osamu Tezuka at his greatest, but it works very well for what it is. Kudos to Vertical for the beautiful paperback packaging. I eagerly await for the rest of the series.

Set during the chaotic Sengoku period, an ambitious warlord makes a faustian bargain with 48 demons to sacrifice his unborn first child in return for greater political power. The baby boy is born with 48 missing body parts. He is left to die from exposure, but is adopted by a kindly surgeon, who later equips him with various prosthetic substitutes (Not bad for a 15th century physician). The child, named Hyakkimaru, grows into an effective demon hunter hoping to kill the demons who stole his body parts, and restore his body. Early on he meets an orphaned street-smart kid named Dororo. They quickly establish an uneasy but friendly rapport, and he joins Hyakkimaru is his quest because he covets the sword blades he carries.

It's truly astonishing how much Tezuka can get away with. The book is filled with so much violence, gore, and nasty supernatural elements, yet feels so thoroughly upbeat. This is in part because Tezuka's art is just so awesome. His monsters and demons are both frightening enough to scare kids while weirdly eccentric enough to amuse older readers. The disfigured baby Hyakkimaru evokes both horror and sympathy for his condition. The adult version makes for a dynamic heroic figure - slashing enemies left and right with katanas hidden inside his prosthetic arms. Tezuka's virtuoso cartooning alone is worth paying the price for this book. Everything from the atmospheric backgrounds to the creature designs are drawn with the confidence of a master comfortable with his craft.

Hyakkimaru and Dororo are easy enough to empathize with. Both are victims of the violent era they live in, and both are looking for ways to rise above their humble beginnings and find personal redemption through hard work. In certain ways they're the template for many shonen heroes that would come afterward. The author's voice clearly sides with the commoners against the samurai class, who are treated as the root of all misery in the world. The protagonists themselves have a lot or reason to be resentful to the samurai class, while enjoying the freedom that comes from their rootless lifestyle.

The parts of the volume that don't deal with the characters back-story focus on episodic action-adventure. The first involves a frog monster/faced-shape tumor that has enslaved an entire village. The second is about a warrior forced to kill by a cursed sword. Tezuka doesn't shy away from presenting the carnage. In fact this book is a useful example of how he mixes serious drama with slapstick comedy, oftentimes in the same panel. By this time Tezuka had already developed an array of quirky comic techniques: characters breaking the fourth wall, cartoon self-portraits, anachronistic asides, and cameos by characters from other comics. Thankfully these gimmicks don't distract too much from the main story.

This isn't Osamu Tezuka at his greatest, but it works very well for what it is. Kudos to Vertical for the beautiful paperback packaging. I eagerly await for the rest of the series.

6/09/2008

Secret Origins

This latest strip from the brilliantly sardonic A Softer World reminded me of Mr. Glass from Unbreakable. Yeah, I too think that M. Night Shyamalan is a hack who doesn't understand comics.

6/08/2008

6/07/2008

Something Old Something Classic

I saw the new Iron Man motion picture recently, and I actually enjoyed it. Most of it had to do with the light touch applied to the plot. Most recent comic book film adaptations have tried to imbue their subject matter with a certain gravitas: The hero is encumbered by a tragic past, has some kind of identity crisis, or is on some kind of quest for revenge. Usually there's some tedious moralizing that accompanies the story. Not that this movie doesn't have a message, or that Tony Stark doesn't have a sense of purpose. Those are staples of the genre. It just doesn't dwell on those bits. There's this unavoidable geopolitical element arising from Stark's career as an arms dealer. And he goes through a conversion experience that leads him to try to rid the world of war, or at least try not to add to it. But incessantly hammering the anti-war message would only heighten the contradictions built into the story. It's about a guy who tries to end war by building the coolest weapon in his private workshop (It's great to be rich). Still the simplistic message has obvious resonance for Americans looking for easy answers. Just don't look at the film too closely.

Then there's the the anti-corporate populist stance presented. Obadiah Shane is the typical evil capitalist who puts the bottom-line before ethical considerations. He berates Tony for not giving his personal creation to Stark Enterprises so the company could profit from it. The irony of the message (no pun intended) comes from the fact that the Iron Man character is a corporate property owned by Marvel, but was the creation of individuals like Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Don Heck and Larry Lieber working in the 60s. They gave up the rights to their creation to the publisher, and Stan Lee gets to have cameos on all the films.

I also finished watching The early 90s Cutey Honey OVA. I haven't had much prior exposure to this particular Go Nagai creation. This is the Japanese equivalent of a project meant to attract older fanboys, only without the continuity-porn and shared universes that plague American superhero comics. I didn't have to watch the 70s anime or read the manga to see that the OVA was basically a homage to those earlier works. A popular argument in favor of the appeal of Japanese comics is that creator ownership has meant that serials eventually end. But if you're like Nagai, turning your creations into successful ongoing franchises is a perfectly sensible option. Cutey Honey is one of those long-lived properties that has never been successfully transplanted to the English-speaking world. It's a bit too classic for most younger western anime fans. From what I understand she is the original transforming superhero of manga. While transformation is used by some American characters (The original Captain Marvel to name the earliest precedent), transformation has become a staple in tokusatsu and magical girl stories. The transformations in Cutey Honey work on one level as empowering fantasies, and on another as voyeuristic entertainment. Every new form is supposed to imbue Honey with new abilities, and she clearly revels in every one of them. But like most superhero costume changes, they seem more aesthetic than functional. That's the fun part of the anime. No two transformation sequences are the same. They're drawn exquisitely with an obvious sexual component.

This is more about exploiting the character's retro charm than about storytelling. The plot is pretty weak. An arch villain is introduced in episode one, but is defeated halfway through the series. The rest of the OVA is composed of disconnected episodes that leave the narrative arc unresolved. Perhaps there were plans for future episodes that never came through. There's definitely a decline in animation quality towards the end. Whatever the case, it feels incomplete. But as someone who grew up watching late 70s anime, the sustained use of a generally light tone and the refusal to update a classic character, or inject adolescent angst and Freudian analysis is much appreciated.

Then there's the the anti-corporate populist stance presented. Obadiah Shane is the typical evil capitalist who puts the bottom-line before ethical considerations. He berates Tony for not giving his personal creation to Stark Enterprises so the company could profit from it. The irony of the message (no pun intended) comes from the fact that the Iron Man character is a corporate property owned by Marvel, but was the creation of individuals like Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Don Heck and Larry Lieber working in the 60s. They gave up the rights to their creation to the publisher, and Stan Lee gets to have cameos on all the films.

I also finished watching The early 90s Cutey Honey OVA. I haven't had much prior exposure to this particular Go Nagai creation. This is the Japanese equivalent of a project meant to attract older fanboys, only without the continuity-porn and shared universes that plague American superhero comics. I didn't have to watch the 70s anime or read the manga to see that the OVA was basically a homage to those earlier works. A popular argument in favor of the appeal of Japanese comics is that creator ownership has meant that serials eventually end. But if you're like Nagai, turning your creations into successful ongoing franchises is a perfectly sensible option. Cutey Honey is one of those long-lived properties that has never been successfully transplanted to the English-speaking world. It's a bit too classic for most younger western anime fans. From what I understand she is the original transforming superhero of manga. While transformation is used by some American characters (The original Captain Marvel to name the earliest precedent), transformation has become a staple in tokusatsu and magical girl stories. The transformations in Cutey Honey work on one level as empowering fantasies, and on another as voyeuristic entertainment. Every new form is supposed to imbue Honey with new abilities, and she clearly revels in every one of them. But like most superhero costume changes, they seem more aesthetic than functional. That's the fun part of the anime. No two transformation sequences are the same. They're drawn exquisitely with an obvious sexual component.

This is more about exploiting the character's retro charm than about storytelling. The plot is pretty weak. An arch villain is introduced in episode one, but is defeated halfway through the series. The rest of the OVA is composed of disconnected episodes that leave the narrative arc unresolved. Perhaps there were plans for future episodes that never came through. There's definitely a decline in animation quality towards the end. Whatever the case, it feels incomplete. But as someone who grew up watching late 70s anime, the sustained use of a generally light tone and the refusal to update a classic character, or inject adolescent angst and Freudian analysis is much appreciated.

6/02/2008

6/01/2008

Diana Prince: Wonder Woman Vol 1

When dealing with any long running comic book franchise, one tends to remember only the highlights - particularly the attempts to shake-up the status quo in order to reverse creative malaise and flagging sales. DC's marquee female super-hero Wonder Woman, seems especially prone to this re-jiggering. Her mixed attribures and fantastic origins tend to inspire conflicting interpretations. She's perhaps even more of a cypher than her male counterparts Superman and Batman. Is she a diplomat, warrior, princess, an innocent abroad, dominatrix, or a feminist symbol? Possibly the oddest effort to redefine her came when writer Dennis O'Neil was given the chance to overhaul the character. What he and collaborating artists Mike Sekowsky and Dick Giordano did was ditch almost every familiar element and recreate her from the ground-up. Their attempt to modernize Wonder Woman failed commercially, and was eventually retconned out of existence. But DC has republished these issues in two paperbacks. Volume 1 contains issues #178-184, which mainly deal with Diana Prince battling the arch-villain Doctor Cyber.

This period of Wonder Woman's published history is sometimes fondly referred to as the "I-Ching Era." O'Neil and company's basic idea was to remove her mythical powers and turn her into a late 60s definition of a modern woman - essentially a comic book version of Emma Peel. When her beau Steve Trevor is arrested on murder charges, Wonder Woman's testimony at his trial ironically leads to his conviction. Diana undergoes a fashion makeover in order to appear more trendy and discover the true murderer. She soon solves the case and clears Steve's name.

However, in the next issue, Steve goes undercover in order to infiltrate Doctor Cyber's criminal organization. Paradise Island is then moved to another dimension in order to recharge its store of magic. Diana chooses to stay on Earth in order to find Steve. Cut-off from her source of power, she quits her job at military intelligence, opens a boutique, and learns karate from I-Ching, a blind Chinese monk whose temple was destroyed by Doctor Cyber. Even without her Amazon abilities she becomes an accomplished fighter within a relatively short span of time.

None of her newly developed skills help save Steve's life when she finally finds him. With his death, Diana has lost the person who first motivated her to leave Paradise Island. She has no love life, no powers, and no double identity. She no longer uses her golden lasso or wears a costume, but dresses in an ever changing wardrobe of fashionable outfits. She drops out of the super-hero community altogether, choosing instead to work with I-Ching in her quest to bring down Dr. Cyber. The new Wonder Woman's world-spanning adventures in this paperback volume fall mostly into the high action/thriller mode of storytelling, but suddenly shift gears to temporarily return Diana back to her mythological roots towards the end of the story arc. It's a curious mix of genres that attempt to expand the limits of Diana's horizons and show the creative staff working hard to find a new direction for her.

Not surprisingly, some elements that may have seemed a novelty in 1968 appears rather dated today. The attempt to capture contemporary youth certainly feels quaint, especially the hippie counterculture, street lingo and the overall psychedelic color scheme. The mystique of Asian forms of fighting was on the rise at the time, and lends credulity to the many hand-to-hand combat scenes. Diana is able to dispatch any number of human and non-human opponents with relative ease. I-Ching is the stereotypical wise oriental dispensing stern discipline and cryptic statements in sometimes broken English.

Despite her proficiency, Diana is depicted as an emotionally fragile person, just like a woman. She tolerates all of Steve Trevor's insensitive remarks, even to the point of blaming herself for his shortcomings. After Steve's death, she develops the habit of falling for the wrong type of guy. There's a lot of weeping when they inevitably disappoint her - hardly the image of the strong, independent modern woman. It's not even the more confident and sexually charged figure from creator William Moulton Martson. Sekowsky's art is just as competent, and his faces just and wooden, as it was during his run at Justice League of America, except he gets to draw Diana Prince in chic clothes while performing faux martial arts poses, ready to execute a "karate chop." To be fair, his ambitious staging of action sequences shows the influence of the more dynamic Marvel Comics in-house style of the time.

In hindsight it's easy to see how this depowered Wonder Woman failed to capture the public imagination. This is as radical a re-imagining of the character as possible - One with the most tenuous connection to her past. But turning Diana into a martial arts sleuth that barely interacted with the rest of the DC Universe didn't sit well with established fans (Which included Gloria Steinem). Still it says something about the character's unpopularity that DC was willing to let Wonder Woman be re-tooled so extensively. And this is an audacious, and in in it's own right noteworthy, undertaking that's highly unlikely with today's continuity-obsessed market.

This period of Wonder Woman's published history is sometimes fondly referred to as the "I-Ching Era." O'Neil and company's basic idea was to remove her mythical powers and turn her into a late 60s definition of a modern woman - essentially a comic book version of Emma Peel. When her beau Steve Trevor is arrested on murder charges, Wonder Woman's testimony at his trial ironically leads to his conviction. Diana undergoes a fashion makeover in order to appear more trendy and discover the true murderer. She soon solves the case and clears Steve's name.

However, in the next issue, Steve goes undercover in order to infiltrate Doctor Cyber's criminal organization. Paradise Island is then moved to another dimension in order to recharge its store of magic. Diana chooses to stay on Earth in order to find Steve. Cut-off from her source of power, she quits her job at military intelligence, opens a boutique, and learns karate from I-Ching, a blind Chinese monk whose temple was destroyed by Doctor Cyber. Even without her Amazon abilities she becomes an accomplished fighter within a relatively short span of time.

None of her newly developed skills help save Steve's life when she finally finds him. With his death, Diana has lost the person who first motivated her to leave Paradise Island. She has no love life, no powers, and no double identity. She no longer uses her golden lasso or wears a costume, but dresses in an ever changing wardrobe of fashionable outfits. She drops out of the super-hero community altogether, choosing instead to work with I-Ching in her quest to bring down Dr. Cyber. The new Wonder Woman's world-spanning adventures in this paperback volume fall mostly into the high action/thriller mode of storytelling, but suddenly shift gears to temporarily return Diana back to her mythological roots towards the end of the story arc. It's a curious mix of genres that attempt to expand the limits of Diana's horizons and show the creative staff working hard to find a new direction for her.

Not surprisingly, some elements that may have seemed a novelty in 1968 appears rather dated today. The attempt to capture contemporary youth certainly feels quaint, especially the hippie counterculture, street lingo and the overall psychedelic color scheme. The mystique of Asian forms of fighting was on the rise at the time, and lends credulity to the many hand-to-hand combat scenes. Diana is able to dispatch any number of human and non-human opponents with relative ease. I-Ching is the stereotypical wise oriental dispensing stern discipline and cryptic statements in sometimes broken English.

Despite her proficiency, Diana is depicted as an emotionally fragile person, just like a woman. She tolerates all of Steve Trevor's insensitive remarks, even to the point of blaming herself for his shortcomings. After Steve's death, she develops the habit of falling for the wrong type of guy. There's a lot of weeping when they inevitably disappoint her - hardly the image of the strong, independent modern woman. It's not even the more confident and sexually charged figure from creator William Moulton Martson. Sekowsky's art is just as competent, and his faces just and wooden, as it was during his run at Justice League of America, except he gets to draw Diana Prince in chic clothes while performing faux martial arts poses, ready to execute a "karate chop." To be fair, his ambitious staging of action sequences shows the influence of the more dynamic Marvel Comics in-house style of the time.

In hindsight it's easy to see how this depowered Wonder Woman failed to capture the public imagination. This is as radical a re-imagining of the character as possible - One with the most tenuous connection to her past. But turning Diana into a martial arts sleuth that barely interacted with the rest of the DC Universe didn't sit well with established fans (Which included Gloria Steinem). Still it says something about the character's unpopularity that DC was willing to let Wonder Woman be re-tooled so extensively. And this is an audacious, and in in it's own right noteworthy, undertaking that's highly unlikely with today's continuity-obsessed market.

5/26/2008

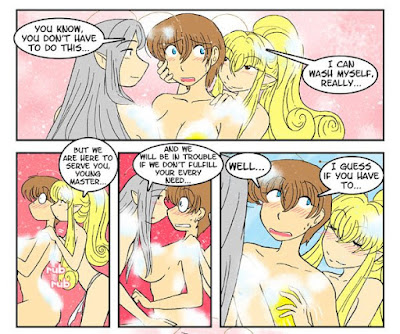

Communal Bathing is Fun

Today's guilty pleasure reading is the "onsen" scene from gender-bending magical girl comedy Sparkling Generation Valkyrie Yuuki (Gosh, what a mouthful!) by Kittyhawk. All that's left now to take place is a beach episode, and oh yeah, a school festival misadventure at Montrose Academy.

The Other: Stories from Closed-off Places

One factor contributing to the respectability of the comics medium is subject-matter. When Art Spiegelman's opus Maus: A Survivor's Tale won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, it prompted the expected round of "comics grow up" articles from the mainstream press. This was a comic that had the audacity to depict the Nazi Holocaust by drawing its characters as anthropomorphized animals. Although the novelty of the graphic novel has since faded, it's no longer unusual for news publications to include comic book reviews, especially if the book's subject-matter is considered weighty enough to warrant serious attention. Today I'm going to examine two such works that attempt to lift the veil behind authoritarian states that have already received considerable media coverage both in the past, and during the present so-called war against terror.

The Complete Persepolis

I only managed to finish Persepolis last week - the critical darling of the mainstream press from a few years back. Set in post-revolutionary Iran, it is the bildungsroman of the author Marjane Satrapi. The book made Time magazine's Best Comix of 2003 list and was awarded a prize at Angoulême. Recently it has been adapted into an animated feature. It's easy to see how this story would get the attention it did. Iran has been labeled an enemy of the West and a source of international terrorism. Satrapi has the added advantage of being an insider. At its heart the real conflict is the inner battle typical of the western-educated elite of many non-western countries: The progressive, secular world view clashing with cherished religious beliefs. An only child of a liberal Muslim family residing in Tehran in the 1980s, Satrapi's rebellion against religious authority as an impetuous teenager causes her parents to send her to Austria. But like most exiles, she's ill at ease in her new environment. The culture shock and isolation eventually get to her. She returns to Iran where she experiences reverse culture shock. At first feeling lonely and depressed, Satrapi resolves to improve herself. When she leaves Iran for the second time, she has developed into a confident, more mature woman.

On paper the author's tale of growing up in modern Iran sounds fascinating. Anything that opens the country to a world that regards it with fear and suspicion, humanizes its citizens, and provides some historical context is a commendable act. So readers are now aware that not everyone in Iran is a card carrying Muslim fanatic. Also important to the work's premise is how the age-old conflict between Arabs and Persians colors the modern-day war between Iraq and Iran. The decision to tell this story as a comic seems particularly clever. As a prose work it would have disappeared amongst all the autobiographies, but as a graphic novel it stands out as something less academic and more accessible.

All of this doesn't change my feeling that subject-matter aside, this is a rather uninspired comic. Marjane Satrapi's use of narrative captions and small panels doesn't particularly make good use of the comic medium. Indeed she doesn't have much to say about it. There's not anything particularly sophisticated about her word-image balance that would make it better than most illustrated prose. While her simple black and white art is easy to follow, it doesn't flow easily from panel to panel. Much of the pace depends on the often digressive narrative text. This lack of grasp of panel transitions makes for a rather disjointed and jerky narrative. As for her characters, while Satrapi is a good enough artist to capture the likeness of a person with a few lines, but there's still something generic about the way they move and act and speak.

Sadly, this applies to the main character of "Marji" herself. She makes for a somewhat interesting kid living in what to western eyes is unusual circumstances. But as she moves from adolescence to adulthood, she doesn't transcend the usual cliches found in coming-of-age tales. She experiences teenage alienation, takes drugs, looses her virginity, falls in love with the wrong guy, breaks-up with him, falls for another guy, gets married. The events themselves aren't the issue, but the banal manner in which they are told. I wanted to like the protagonist, but I didn't find myself caring for her when I finally put the book down. Instead I was making unfavorable comparisons to David B's much more accomplished autobiography Epileptic. This leaves me in two minds about Persepolis. On one hand I can't begrudge the success of a book. But I wouldn't recommend it as a shining example of the comics medium.

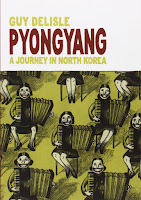

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

Pyongyang is a travelogue by Canadian Quebecois comics creator Guy Delisle. It chronicles his two month stay in that city working as a liaison between a French animation studio and the North Korean animators the company has outsourced its work to. All North Korean animators work at the state-controlled Scientific Educational Korea (SEK). During his time there, Delisle stayed in one of three hotels built to house foreign expatriate workers. He was never allowed to leave the hotel unattended. At all times he was required to be accompanied by a state-assigned guide or translator.

Right of the bat Delisle takes some self-conscious pride in being an outsider to the system. He brings a copy of George Orwell's anti-totalitarian novel 1984, noting that none of the locals seem to recognize its subversive nature. He even lends it to his translator at one point, which predictably produces an upset reaction later on. He also brings CDs of music designed to provoke the locals (reggae, jazz, and electronic music artist Aphex Twin) and even smuggles in a transistor radio - a contraband item.

Delisle is an entertaining storyteller. He's a cynical and funny observer: taking note of little details from the local fashions, to the immaculate condition of the city streets, to the ubiquitous and strangely similar portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Throughout the book he peppers his story with the kind of information accessible to him from outside of North Korea, but never shares with the locals. For example when discussing the reunification issue between North and South Korea with his translator (which he insists on calling "captain" Sin), he doesn't argue against the claim that the United States is the primary opponent to blocking reunification, but expresses his opinion to the reader that North Korea's own poverty and military build-up are a bigger obstacle to reunification. As a westerner, he is constantly aware of the of the censorship, paranoia, and repression which the North Koreans do not address. The only time he can talk freely is when he is around colleagues and other members of the expatriate community, which constitutes an island of cosmopolitanism carefully segregated from the rest of the population.

At the same time, the North Korean government never let's an opportunity to propagandize to anyone go to waste. Every weekend Delisle is invited by his guide to visit some national monument or site dedicated to the cult of Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il. he dutifully follows his guides around, but it soon gets to be too much for him. When asked by them what he thought of America after seeing a museum exhibit depicting alleged war crimes commited by American soldiers during the Korean War, Delisle makes light of those atrocities in an attempt to sound fair and balanced. They are not amused his response.

This is a significant limitation of Delisle's story. He knows how totalitarian the North Korean regime is, and wonders whether his guide and translator do: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" But they in turn seem equally convinced that Kim Il Sung is the greatest leader on Earth, and North Korea is the world's greatest nation. His inability to cross the huge gap in perception between foreigners and locals is what prevents Delisle from coming up with anything more insightful a conclusion than that ordinary North Koreans have been cowed by fear of retribution from the state - something he had already learned from Orwell. Delisle is no Joe Sacco. He's never able to penetrate the exotic strangeness of the country, or get past the ideological mask and connect with the North Koreans as individuals. I imagine that his guide and translator probably saw him as an odd and condescending westerner. But that's to be expected given the restrictions placed on him. Between the hotel and his job at the SEK, Delisle didn't have the time or the initiative to do much else. Considering these circumstances and the immensity of the cultural divide, the most he could probably ever hope to do was bond with his hosts over a good meal and a bottle of Hennessy.

The Complete Persepolis

I only managed to finish Persepolis last week - the critical darling of the mainstream press from a few years back. Set in post-revolutionary Iran, it is the bildungsroman of the author Marjane Satrapi. The book made Time magazine's Best Comix of 2003 list and was awarded a prize at Angoulême. Recently it has been adapted into an animated feature. It's easy to see how this story would get the attention it did. Iran has been labeled an enemy of the West and a source of international terrorism. Satrapi has the added advantage of being an insider. At its heart the real conflict is the inner battle typical of the western-educated elite of many non-western countries: The progressive, secular world view clashing with cherished religious beliefs. An only child of a liberal Muslim family residing in Tehran in the 1980s, Satrapi's rebellion against religious authority as an impetuous teenager causes her parents to send her to Austria. But like most exiles, she's ill at ease in her new environment. The culture shock and isolation eventually get to her. She returns to Iran where she experiences reverse culture shock. At first feeling lonely and depressed, Satrapi resolves to improve herself. When she leaves Iran for the second time, she has developed into a confident, more mature woman.

On paper the author's tale of growing up in modern Iran sounds fascinating. Anything that opens the country to a world that regards it with fear and suspicion, humanizes its citizens, and provides some historical context is a commendable act. So readers are now aware that not everyone in Iran is a card carrying Muslim fanatic. Also important to the work's premise is how the age-old conflict between Arabs and Persians colors the modern-day war between Iraq and Iran. The decision to tell this story as a comic seems particularly clever. As a prose work it would have disappeared amongst all the autobiographies, but as a graphic novel it stands out as something less academic and more accessible.

All of this doesn't change my feeling that subject-matter aside, this is a rather uninspired comic. Marjane Satrapi's use of narrative captions and small panels doesn't particularly make good use of the comic medium. Indeed she doesn't have much to say about it. There's not anything particularly sophisticated about her word-image balance that would make it better than most illustrated prose. While her simple black and white art is easy to follow, it doesn't flow easily from panel to panel. Much of the pace depends on the often digressive narrative text. This lack of grasp of panel transitions makes for a rather disjointed and jerky narrative. As for her characters, while Satrapi is a good enough artist to capture the likeness of a person with a few lines, but there's still something generic about the way they move and act and speak.

Sadly, this applies to the main character of "Marji" herself. She makes for a somewhat interesting kid living in what to western eyes is unusual circumstances. But as she moves from adolescence to adulthood, she doesn't transcend the usual cliches found in coming-of-age tales. She experiences teenage alienation, takes drugs, looses her virginity, falls in love with the wrong guy, breaks-up with him, falls for another guy, gets married. The events themselves aren't the issue, but the banal manner in which they are told. I wanted to like the protagonist, but I didn't find myself caring for her when I finally put the book down. Instead I was making unfavorable comparisons to David B's much more accomplished autobiography Epileptic. This leaves me in two minds about Persepolis. On one hand I can't begrudge the success of a book. But I wouldn't recommend it as a shining example of the comics medium.

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

Pyongyang is a travelogue by Canadian Quebecois comics creator Guy Delisle. It chronicles his two month stay in that city working as a liaison between a French animation studio and the North Korean animators the company has outsourced its work to. All North Korean animators work at the state-controlled Scientific Educational Korea (SEK). During his time there, Delisle stayed in one of three hotels built to house foreign expatriate workers. He was never allowed to leave the hotel unattended. At all times he was required to be accompanied by a state-assigned guide or translator.

Right of the bat Delisle takes some self-conscious pride in being an outsider to the system. He brings a copy of George Orwell's anti-totalitarian novel 1984, noting that none of the locals seem to recognize its subversive nature. He even lends it to his translator at one point, which predictably produces an upset reaction later on. He also brings CDs of music designed to provoke the locals (reggae, jazz, and electronic music artist Aphex Twin) and even smuggles in a transistor radio - a contraband item.

Delisle is an entertaining storyteller. He's a cynical and funny observer: taking note of little details from the local fashions, to the immaculate condition of the city streets, to the ubiquitous and strangely similar portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Throughout the book he peppers his story with the kind of information accessible to him from outside of North Korea, but never shares with the locals. For example when discussing the reunification issue between North and South Korea with his translator (which he insists on calling "captain" Sin), he doesn't argue against the claim that the United States is the primary opponent to blocking reunification, but expresses his opinion to the reader that North Korea's own poverty and military build-up are a bigger obstacle to reunification. As a westerner, he is constantly aware of the of the censorship, paranoia, and repression which the North Koreans do not address. The only time he can talk freely is when he is around colleagues and other members of the expatriate community, which constitutes an island of cosmopolitanism carefully segregated from the rest of the population.

At the same time, the North Korean government never let's an opportunity to propagandize to anyone go to waste. Every weekend Delisle is invited by his guide to visit some national monument or site dedicated to the cult of Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il. he dutifully follows his guides around, but it soon gets to be too much for him. When asked by them what he thought of America after seeing a museum exhibit depicting alleged war crimes commited by American soldiers during the Korean War, Delisle makes light of those atrocities in an attempt to sound fair and balanced. They are not amused his response.

This is a significant limitation of Delisle's story. He knows how totalitarian the North Korean regime is, and wonders whether his guide and translator do: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" But they in turn seem equally convinced that Kim Il Sung is the greatest leader on Earth, and North Korea is the world's greatest nation. His inability to cross the huge gap in perception between foreigners and locals is what prevents Delisle from coming up with anything more insightful a conclusion than that ordinary North Koreans have been cowed by fear of retribution from the state - something he had already learned from Orwell. Delisle is no Joe Sacco. He's never able to penetrate the exotic strangeness of the country, or get past the ideological mask and connect with the North Koreans as individuals. I imagine that his guide and translator probably saw him as an odd and condescending westerner. But that's to be expected given the restrictions placed on him. Between the hotel and his job at the SEK, Delisle didn't have the time or the initiative to do much else. Considering these circumstances and the immensity of the cultural divide, the most he could probably ever hope to do was bond with his hosts over a good meal and a bottle of Hennessy.

5/18/2008

Linux Humor

Now this is really geeky. Randall Munroe knocks the more prominent Linux distros. Thank God for the internet. But wow! Ubuntu received the most unkind cut.

5/10/2008

Animania Festival 2008: So Many Joshikousei

Yesterday I finally did what I've been avoiding since 2004 - I bought a new set of SLR camera lenses to replace the ones I've been using up to now. When I made the move to digital photography, I continued to use my old Nikon 35 mm lenses (Backward compatibility is a wonderful thing). But they've aged rather badly since then. The rubber started to come loose, and on one lens the Aperture adjustment became unresponsive. Retirement was inevitable. The last straw was the Brisbane Supanova convention. Too many photos came out flat, blurry, or suffering from a bad case of lens flare. I couldn't shoot with my equipment anymore if I wanted acceptable results. So after much deliberation I purchased a pair of Nikkor DX lenses with VR capabilities: One wide angle and one telephoto. They're not my top choices, but given my present financial situation, they were all I could afford. The ones I really want alas still remain wishlist items. In certain respects their handling and performance is inferior to my old lenses when they were in top condition. But they make up for that by returning to me the wider angle view I lost when I started to shoot with a DX body. In addition the VR feature has saved what would have been otherwise unusable photos.

Why am I relaying all this? Because what eventually got me to buy new photographic equipment is the topic of this post: Today's Animania Festival . The most appropriate word to describe the one day mini event would be "intimate." It occupied the fifth floor of the local Holiday Inn, filling the hall and the four conference rooms - One for vendors, two for anime screenings, and the largest for main events like the cosplay competition. Running from 10 AM - 4 PM, the organizers kept things moving by packing the schedule with activities like games shows, demonstrations, karaoke, contests, all carried out by a small but enthusiastic group of staffers from (I presume) the main convention in Sydney. It's a typical anime-themed convention. But the franchise's local success has lead to the announcement of a second Animania for Brisbane later this year in September. What anyone would have to look forward to in another Animania is beyond me.

The other big news (It's big news if you're a cosplayer) is that the Animania franchise is participating in the selection of representatives for the World Cosplay Summit. I'm not familiar with the event, but the Japanese government seems to support it as a means to promote the country's "soft power" abroad. Only two contestants showed-up to fill the two spots for the next stage of the preliminaries to be held in Sydney, so there was no real suspense about not qualifying. Unlike the usual cosplay contest, the participants, in addition to performing a cosplay skit, were asked a series of questions from a panel of judges, reminiscent of a beauty contest or job interview: They had to field the usual obvious queries like "Why do you think you should represent Australia at the WCS?" or "How would you improve your act?" Off course every contestant wanted to go to Japan. I myself would like to tag along with them just to watch Japanese otaku in their native element.

Comics-wise there's nothing to talk about. This is a pure fan convention - more celebratory than critical. Not a single manga or anime professional was seen or heard. The only panel being held was about cosplaying. Substance was never Animania's strong suit. But today I had new equipment I was dying to field test, and that's what I did. My first photo post is already up with more on the way.

5/04/2008

A Look at Free Comic Book Day

Free Comic Book Day has come and gone. I'm mostly skeptical about the event's ability to bring in new readers. Much of its success or failure depends on the particular retailer's ability to attract people who would usually not step into a comic book store. There are three of them within a block of each other at Brisbane's commercial center. One didn't bother to participate. The second allowed only one free comic per shopper. The last hung balloons on the walls to lure customers up to its 3rd story entrance. While business was brisk, it didn't seem like anyone besides the usual comic book crowd was shopping inside. I thought I'd evaluate three books for their ability to attract potential readers.

IGNATZ

I'm pleased to see this book being offered during FCBD. None of the material is self-contained, but excerpts of much longer stories. As a sampler it's pretty much what I would expect from a high-end art comics line published by Fantagraphics, which is to say it's good, mostly non-genre work. David B's autobiographical Epileptic was a masterpiece of surreal storytelling. His sequel Babel, which continues to record the mental deterioration of his older brother, seems no less accomplished. Another intriguing feauture is Kevin Huizenga's stories of everyman hero Glenn Ganges (Also published by Drawn and Quarterly). So is Richard Sala's gothic retelling of a classic fairy-tale in Delphine.

All of the stories are worth examining further, but your mileage may vary. A certain aesthetic can be found in most of the comics: The solid, organic, line-work, the monochromatic coloring, the six-panel grid, and the European-leaning definition for "international." It doesn't showcase flashy black and white manga-style, or cute anthropomorphic art. Unfortunately the cheap printing quality doesn't do it any favors. The IGNATZ acronym feels clumsy and pretentious. I doubt this comic book line will attract readers who aren't already familiar with Fantagraphics' output, but those who are beginning to explore the medium beyond the confines of formulaic entertainment will want to read it.

DC Universe 0

Technically not an FCBD offering, but the retailer was giving it away. I'm obviously not the first to say this, but DC's and Marvel's super-hero lines have difficulty pulling in new readers. What do you expect when the publisher chooses to advance a convoluted shared universe mired with decades worth of continuity? DC Universe 0 is structured like a movie trailer: A short teaser is followed by a portentous full-page ad tying the story to the upcoming crossover event Final Crisis. DC's biggest names are under threat: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, and the Spectre (So what else is new?). A super-villain society is formed that worships a dark new god. And a long-dead hero returns in a flash of lightning.

if you don't get the references, then you're not hard-core enough. The person this is meant to appeal to, other than the longtime fanboy, is the older lapsed reader - someone who's at least been around since Crisis on Infinite Earths and has been out-of-touch. I'm sure there are plenty of them out there. Heck I'm one of them. And no I'm not really interested in returning from the look of things here. It's all too depressing just thinking about it.

Amelia Rules!

Hey, a comic book that's meant for kids. Appropriately cute artwork for the target audience. According to its creator Jimmy Gownley, he is abandoning the pamphlet format for paperback, which is a better fit for the bookstore market (news source here). The lead story is surprisingly weighty because it ties in with a larger work about a reservist father drafted to fight in Iraq. Unfortunately the subject-matter threatens to crush any forward momentum. As the characters try to make sense of a war they cannot understand, the number of talking-head panels increases, and the info-dump eventually grinds things to a halt. If the execution isn't quite successful, I imagine that children grappling with these very issues will find it relevant. Not the most whimsical material for its intended demographic.

Some Notes:

I'm dissapointed that none of the retailers I visited stocked copies of Gegika. That would have made an excellent stylistic contrast to IGNATZ, and a counterpoint to the more mainstream Shonen Jump. The latter book's excerpts should be familiar to its readers, but otherwise mostly confuse the uninitiated, except for Slam Dunk, which Viz seems to be banking on as its next hit. I didn't need to pick-up All Star Superman #1, already owning a copy. It's a logical choice - being largely free of the trappings of the DC Universe, and revisiting Silver-Age concepts familiar to the general public. It's well-written and drawn, but I doubt it will interest anyone who thinks Superman is old-fashioned, and the whiff of nostalgia inevitably creeps into the story. I also glanced at Tiny Titans #1, which was something of a disappointment. It's funny and cute, but unless the six year olds this is aimed at are fanboys themselves, many of the jokes are going to go over their heads.

IGNATZ

I'm pleased to see this book being offered during FCBD. None of the material is self-contained, but excerpts of much longer stories. As a sampler it's pretty much what I would expect from a high-end art comics line published by Fantagraphics, which is to say it's good, mostly non-genre work. David B's autobiographical Epileptic was a masterpiece of surreal storytelling. His sequel Babel, which continues to record the mental deterioration of his older brother, seems no less accomplished. Another intriguing feauture is Kevin Huizenga's stories of everyman hero Glenn Ganges (Also published by Drawn and Quarterly). So is Richard Sala's gothic retelling of a classic fairy-tale in Delphine.

All of the stories are worth examining further, but your mileage may vary. A certain aesthetic can be found in most of the comics: The solid, organic, line-work, the monochromatic coloring, the six-panel grid, and the European-leaning definition for "international." It doesn't showcase flashy black and white manga-style, or cute anthropomorphic art. Unfortunately the cheap printing quality doesn't do it any favors. The IGNATZ acronym feels clumsy and pretentious. I doubt this comic book line will attract readers who aren't already familiar with Fantagraphics' output, but those who are beginning to explore the medium beyond the confines of formulaic entertainment will want to read it.

DC Universe 0

Technically not an FCBD offering, but the retailer was giving it away. I'm obviously not the first to say this, but DC's and Marvel's super-hero lines have difficulty pulling in new readers. What do you expect when the publisher chooses to advance a convoluted shared universe mired with decades worth of continuity? DC Universe 0 is structured like a movie trailer: A short teaser is followed by a portentous full-page ad tying the story to the upcoming crossover event Final Crisis. DC's biggest names are under threat: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, and the Spectre (So what else is new?). A super-villain society is formed that worships a dark new god. And a long-dead hero returns in a flash of lightning.

if you don't get the references, then you're not hard-core enough. The person this is meant to appeal to, other than the longtime fanboy, is the older lapsed reader - someone who's at least been around since Crisis on Infinite Earths and has been out-of-touch. I'm sure there are plenty of them out there. Heck I'm one of them. And no I'm not really interested in returning from the look of things here. It's all too depressing just thinking about it.

Amelia Rules!

Hey, a comic book that's meant for kids. Appropriately cute artwork for the target audience. According to its creator Jimmy Gownley, he is abandoning the pamphlet format for paperback, which is a better fit for the bookstore market (news source here). The lead story is surprisingly weighty because it ties in with a larger work about a reservist father drafted to fight in Iraq. Unfortunately the subject-matter threatens to crush any forward momentum. As the characters try to make sense of a war they cannot understand, the number of talking-head panels increases, and the info-dump eventually grinds things to a halt. If the execution isn't quite successful, I imagine that children grappling with these very issues will find it relevant. Not the most whimsical material for its intended demographic.

Some Notes:

I'm dissapointed that none of the retailers I visited stocked copies of Gegika. That would have made an excellent stylistic contrast to IGNATZ, and a counterpoint to the more mainstream Shonen Jump. The latter book's excerpts should be familiar to its readers, but otherwise mostly confuse the uninitiated, except for Slam Dunk, which Viz seems to be banking on as its next hit. I didn't need to pick-up All Star Superman #1, already owning a copy. It's a logical choice - being largely free of the trappings of the DC Universe, and revisiting Silver-Age concepts familiar to the general public. It's well-written and drawn, but I doubt it will interest anyone who thinks Superman is old-fashioned, and the whiff of nostalgia inevitably creeps into the story. I also glanced at Tiny Titans #1, which was something of a disappointment. It's funny and cute, but unless the six year olds this is aimed at are fanboys themselves, many of the jokes are going to go over their heads.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)