Go to: The Nib, by Meg O'Shea

Showing posts with label travel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label travel. Show all posts

1/15/2018

10/27/2017

Video: (unofficial) History of the National Parks

Go to: Aeon, by Ryan Maxey

10/14/2017

Video: 30 Days Timelapse at Sea

Go to: JeffHK, by Jeffrey Tsang (via Jason Kottke)

8/05/2017

5/12/2014

Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City

Colors by Lucie Firoud and Guy Delisle

Translated by Helge Dascher

Cartoonist Guy Delisle has carved out a special niche writing about strange foreign lands. That’s his approach to Pyongyang and Burma Chronicles. Noting the strangeness of a place may not be particularly insightful analysis, but it works perfectly for Delisle. His stockpiling of numerous insignificant details mirrors how most clueless Westerners experience the rest of the world. Delisle has become the spokesperson for early stage culture shock because he never achieves true mastery of his subject. Not that he seems to care. Even when set in a country that would supposably be more familiar to Delisle’s readers, Jerusalem: Chronicles from The Holy City still follows in the footsteps of those past travelogues. But when the same style is applied to this more ambitious work, its homespun charms are stretched and bloated, and ultimately exposed as a kind of careless affectation.

Delisle’s cartoon avatar always begins his journey as a blank slate, as if he’s never travelled abroad or did any prior research, and this ersatz naiveté mimics the gap between tourist and native. In this case, his self-enforced blandness provides a peculiar contrast to his tumultuous surroundings. Jerusalem is, above all else, a city mired in identity politics. Delisle acts perplexed when it’s explained to him that the international community doesn’t recognize the city as Israel’s capital (which left me incredulous. Is he that unaware of the Arab-Israeli conflict?). The first visible symbol of how identity has altered the landscape is when Delisle visits a checkpoint at the infamous West Bank/Israel separation wall and watches as the guards fire tear gas into the crowd when responding to a minor disturbance.

That wall becomes a favorite motif of his, a metaphor for a country defined by every kind of barrier. Delisle learns to avoid the “Ultra-Orthodox” Jewish enclave Mea Shearim, especially after noticing a sign that warns outsiders to stay away. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is managed by six Christian denominations whose representatives behave like rival street gangs. After watching a news report about a celebration at the church that comes to blows, Delisle delivers a rather banal (and tone deaf) remark “But when you think that Christians can’t even set an example in a conflict that’s polarized the world for so long, it’s a bit depressing....” then thanks God for being an atheist. Delisle visits the once bustling city of Hebron, now the battleground for Palestinians and Jewish settlers fighting over the sacred Cave of the Patriarchs. Netting is hung above the streets to protect Muslims from garbage tossed at their direction by the settlers. And he tries to come to grips with the clash over the two most high profile religious landmarks in all of Jerusalem, the Wailing Wall and the Dome on the Rock, noting the queer alliance between conservative Jews and fundamentalist Christians who believe that knocking down the mosque to rebuild the temple is a prerequisite to bringing about the Biblical Apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ.

To a nonbeliever like Delisle, these barriers present a huge headache. It makes the city a confusing maze of no-go zones linked by disparate forms of public transportation serving different segregated neighborhoods. When he gets lost and accidentally drives into Mea Shearim during the Sabbath, he’s attacked by an angry mob. It complicates normal routines like shopping and driving the kids to school, not to mention exploring the rest of the country. Extremely paranoid airport security makes Delisle's occasional brief trips abroad almost intolerable. His most self-aware line is delivered after he learns that the border authorities have rejected his request to conduct a comics workshop in Gaza. A colleague informs Delisle “They said, ‘The guy who draws comics? Forget it.’” This causes him to wonder “Maybe they've got me mixed up with Joe Sacco?” Like many of the expat community he regularly interacts with, Delisle is vaguely sympathetic to the plight of the Palestinians. As in Burma, he’s accompanying his significant other, who works for the humanitarian organization Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). And as with Burma, it’s also the cause of his emotional detachment. Delisle knows the assignment will last only a year and that he will not develop a deeper relationship with the place. But each of Israel's varied groups believe they have an irrefutable connection to this slither of land which precludes everyone else's claims. The Palestinians in particular appear to have no choice but to keep fighting for their ever-shrinking share of territory if they don't want to loose it to an implacable foe. Palestinian cartoonists and illustrators in Gaza are prevented from getting work in Jerusalem. But as an outsider and rootless cosmopolitan, Delisle has the freedom, or rather the privilege, to leave at any time.

And as with Burma, it’s not really about the host country itself, but about Delisle’s own bumbling efforts to adjust to said country’s weird customs. In smaller doses, his everyman schtick can be amusing. The multi-ethnic setting provides plenty of opportunity for Delisle to exercise his gift for caricature. But spread over a discursive, three hundred page graphic novel, the facile storytelling can start to grate. Do I really need to hear about every quiet spot or nice place to grab a bite? Or every bothersome checkpoint? Must I listen about how difficult it is to find good housekeepers or babysitters? Or Delisle drawing himself complain about how he’s too harried from taking care of the kids to actually draw? Jerusalem was the first Delisle travelogue I found a chore to get through at around the halfway point. Delisle also spent a fair amount of time recounting his domestic situation in Burma. Problem is his family portrait is equally nondescript. His SO’s job at MSF is barely discussed, let alone her unique viewpoint on the situation, and his two generically cute children are sort of a black hole that suck up much of Delisle’s time and energy. This saps reader interest the way being forced to look at someone else’s family vacation pictures would drain most people.

The lack of an overarching narrative over such a lengthy book draws attention to the limitations of the art. Delisle employs the occasional splash of intense color to break up the monotony. This just underlines the ugliness of the monochrome color scheme, exacerbated by the geometric flatness, minimal characterizations and wide-angle perspective. Delisle’s overall aesthetic hasn’t evolved much since Pyongyang, but at this point his commitment to it starts to either look like a withdrawal into a protective shell, or maybe a form of artistic laziness. Whatever the reason, Delisle remains mostly a master of the incidental.

Translated by Helge Dascher

Cartoonist Guy Delisle has carved out a special niche writing about strange foreign lands. That’s his approach to Pyongyang and Burma Chronicles. Noting the strangeness of a place may not be particularly insightful analysis, but it works perfectly for Delisle. His stockpiling of numerous insignificant details mirrors how most clueless Westerners experience the rest of the world. Delisle has become the spokesperson for early stage culture shock because he never achieves true mastery of his subject. Not that he seems to care. Even when set in a country that would supposably be more familiar to Delisle’s readers, Jerusalem: Chronicles from The Holy City still follows in the footsteps of those past travelogues. But when the same style is applied to this more ambitious work, its homespun charms are stretched and bloated, and ultimately exposed as a kind of careless affectation.

Delisle’s cartoon avatar always begins his journey as a blank slate, as if he’s never travelled abroad or did any prior research, and this ersatz naiveté mimics the gap between tourist and native. In this case, his self-enforced blandness provides a peculiar contrast to his tumultuous surroundings. Jerusalem is, above all else, a city mired in identity politics. Delisle acts perplexed when it’s explained to him that the international community doesn’t recognize the city as Israel’s capital (which left me incredulous. Is he that unaware of the Arab-Israeli conflict?). The first visible symbol of how identity has altered the landscape is when Delisle visits a checkpoint at the infamous West Bank/Israel separation wall and watches as the guards fire tear gas into the crowd when responding to a minor disturbance.

That wall becomes a favorite motif of his, a metaphor for a country defined by every kind of barrier. Delisle learns to avoid the “Ultra-Orthodox” Jewish enclave Mea Shearim, especially after noticing a sign that warns outsiders to stay away. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is managed by six Christian denominations whose representatives behave like rival street gangs. After watching a news report about a celebration at the church that comes to blows, Delisle delivers a rather banal (and tone deaf) remark “But when you think that Christians can’t even set an example in a conflict that’s polarized the world for so long, it’s a bit depressing....” then thanks God for being an atheist. Delisle visits the once bustling city of Hebron, now the battleground for Palestinians and Jewish settlers fighting over the sacred Cave of the Patriarchs. Netting is hung above the streets to protect Muslims from garbage tossed at their direction by the settlers. And he tries to come to grips with the clash over the two most high profile religious landmarks in all of Jerusalem, the Wailing Wall and the Dome on the Rock, noting the queer alliance between conservative Jews and fundamentalist Christians who believe that knocking down the mosque to rebuild the temple is a prerequisite to bringing about the Biblical Apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ.

To a nonbeliever like Delisle, these barriers present a huge headache. It makes the city a confusing maze of no-go zones linked by disparate forms of public transportation serving different segregated neighborhoods. When he gets lost and accidentally drives into Mea Shearim during the Sabbath, he’s attacked by an angry mob. It complicates normal routines like shopping and driving the kids to school, not to mention exploring the rest of the country. Extremely paranoid airport security makes Delisle's occasional brief trips abroad almost intolerable. His most self-aware line is delivered after he learns that the border authorities have rejected his request to conduct a comics workshop in Gaza. A colleague informs Delisle “They said, ‘The guy who draws comics? Forget it.’” This causes him to wonder “Maybe they've got me mixed up with Joe Sacco?” Like many of the expat community he regularly interacts with, Delisle is vaguely sympathetic to the plight of the Palestinians. As in Burma, he’s accompanying his significant other, who works for the humanitarian organization Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). And as with Burma, it’s also the cause of his emotional detachment. Delisle knows the assignment will last only a year and that he will not develop a deeper relationship with the place. But each of Israel's varied groups believe they have an irrefutable connection to this slither of land which precludes everyone else's claims. The Palestinians in particular appear to have no choice but to keep fighting for their ever-shrinking share of territory if they don't want to loose it to an implacable foe. Palestinian cartoonists and illustrators in Gaza are prevented from getting work in Jerusalem. But as an outsider and rootless cosmopolitan, Delisle has the freedom, or rather the privilege, to leave at any time.

And as with Burma, it’s not really about the host country itself, but about Delisle’s own bumbling efforts to adjust to said country’s weird customs. In smaller doses, his everyman schtick can be amusing. The multi-ethnic setting provides plenty of opportunity for Delisle to exercise his gift for caricature. But spread over a discursive, three hundred page graphic novel, the facile storytelling can start to grate. Do I really need to hear about every quiet spot or nice place to grab a bite? Or every bothersome checkpoint? Must I listen about how difficult it is to find good housekeepers or babysitters? Or Delisle drawing himself complain about how he’s too harried from taking care of the kids to actually draw? Jerusalem was the first Delisle travelogue I found a chore to get through at around the halfway point. Delisle also spent a fair amount of time recounting his domestic situation in Burma. Problem is his family portrait is equally nondescript. His SO’s job at MSF is barely discussed, let alone her unique viewpoint on the situation, and his two generically cute children are sort of a black hole that suck up much of Delisle’s time and energy. This saps reader interest the way being forced to look at someone else’s family vacation pictures would drain most people.

The lack of an overarching narrative over such a lengthy book draws attention to the limitations of the art. Delisle employs the occasional splash of intense color to break up the monotony. This just underlines the ugliness of the monochrome color scheme, exacerbated by the geometric flatness, minimal characterizations and wide-angle perspective. Delisle’s overall aesthetic hasn’t evolved much since Pyongyang, but at this point his commitment to it starts to either look like a withdrawal into a protective shell, or maybe a form of artistic laziness. Whatever the reason, Delisle remains mostly a master of the incidental.

7/15/2013

Shelf Porn: Chinese Tankōbon

Go to: My Photoblog.

Photos taken by me at Hiro Comic World, Chinatown, Kuala Lumpur. If only the store’s copies weren’t localized for Cantonese speakers, they’d be perfect for me. This is the most manga I’ve seen with my own eyes in a single setting. They also had plenty of anime and Korean dramas on disc.

8/22/2010

Burma Chronicles

In one of the more self-reflexive moments of Burma Chronicles, creator and main protagonist Guy Delisle notices a reproduction of a few Tintin panels. "Good old Tintin! That guy is everywhere!" he says admiringly. Like his predecessor Hergé, Delisle spins tales set in far-away exotic places. But whereas the Franco-Belgian master's stories reveal the clear-cut divisions of their colonialist, Cold War era settings, Delisle lives in the murkier post-colonial, and post-9-11, present. In Shenzen and Pyongyang (which I reviewed here) he is an agent of globalization - he supervises the tedious inbetween work that virtually all major studios, still using traditional animation, nowadays dole out to inexpensive Asian labor. In Burma Chronicles he accompanies his wife Nadège, an administrator for Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). While Nadège has to contend with the increasingly secretive and controlling military junta that rules Burma (or Myanmar as they prefer to call the country), Delisle works part-time on his comics while being a stay-at-home dad who takes care of the couple's infant son Louis.

As with his past works, Delisle blends political commentary with his own experiences working and living as an expat in these authoritarian states. There are strengths and limitations to this approach. Delisle isn't an investigative reporter, so his first-hand sources are mostly confined to street-level information acquired from co-workers, colleagues, friends and neighbors. But this has the advantage of making his commentary easier to absorb when the reader can observe how they affect Delisle and the ordinary people around him. During his yearlong stay in Rangoon, he accumulates a wealth a experience which he relates in vignettes composed anywhere from one page to half a dozen pages. For example, he mentions how the government literally cuts out offending material in foreign publications. He reveals that he lives near the home of celebrated opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and how she is referred to only as The Lady by the general population. He mentions seeing a Marilyn Manson t-shirt when out shopping, but that fans have to go to neighboring Thailand to buy his music recordings. He discusses the technical difficulties getting internet access when there are only two ISPs in the entire country: "...One belongs to a government minister, the other to his son.” All these anecdotes build-up to a picture of Burma as a country that despite its international isolation, its citizens are aware that they are being manipulated and have adjusted their behavior accordingly to deal with living inside a police state.* As with Pyongyang, Delisle conveys all this with his usual humorous and disaffected tone combined with an accessible drawing style which economically conveys actions, information and quick impressions to the reader.

One complaint I had with Pyongyang was that Delisle the character was never able to connect with the local population in any meaningful way. This could be explained by both the state's particularly hash form of totalitarianism and the nature of his job. But Delisle himself contributed to the problem with his own lassitude and sense of detachment. Delisle starts off being similarly ensconced within his expat bubble. He spends much of the early part of the book dealing with how his family settled into their new routine. As the book progresses, Delisle's world expands beyond his family, work colleagues, his fellow expats. He forms associations with local Burmese, particularly the community of Burmese cartoonists. He even begins to teach animation to some of them. The scope of the book also expands beyond seeing the country in purely political terms as Delisle takes a slightly bemused look at Burmese customs: from the incessant betel-chewing to the place Buddhism has in its culture. He also recounts through wordless interludes the various vacations he and his wife took during their stay. as a result, Burma Chronicles is far more rambling and episodic than Pyongyang. And some vignettes are more effective than others. While the political situation informs the entire book, it's obvious that this is primarily a memoir about Delisle's time in Burma.

This intersection between the personal and the political impacts the story in certain ways. The first is that for all the familiarity he develops with the local environment, Delisle remains a foreign visitor - namely a person from an affluent Western liberal democracy who can theoretically leave any time the situation becomes unpleasant. This is what actually happens towards the end as the junta makes the MSF mission virtually impossible to carry out.** Delisle travels to Burma secure in the knowledge that Nadège's position is just as temporary as all her previous MSF postings, and the reader naturally assumes that Delisle will come out of it more or less intact if he is to complete this book. The laid-back mood that permeates his travelogues keeps the reader at a slight distance from both the difficulties encountered within the host country, and Delisle himself.

The second is that even though Delisle gets to socialize with many Burmese in a more informal manner than with the North Koreans in Pyongyang, the book is unusually circumspect about them. He only directly names a few ordinary Burmese citizens, mainly his household staff. None of them are fleshed-out as his fellow expats. This inequality is a quite glaring omission in the book. The most generous interpretation of this is suggested by one incident: Delisle's of-the-cuff remarks to a visiting journalist come back to bite him when one of his animation students, a government employee, vanishes with no explanation. Delisle never feels like he's in danger. But he suspects that the student was punished for being associated with him. No one who makes critical remarks about the regime is ever identified within the book.

And this is where Burma Chronicles leaves the reader. It's entertaining and informative. It's not as forthright as a journalistic expose. Nor is it quite as intimate as it implies it could have been. But it's a tantalizing glimpse into a place that is little understood by many people from Delisle's background.

___

* On a personal note, the local conditions of Burma described in this book remind me of the Philippines under the Martial Law years, combined with the added burden of its pariah state status.

** In one of the more interesting conversations that Delisle records, an MSF employee offers several, not always flattering, explanations on why other international NGOs continue to work in Burma.

As with his past works, Delisle blends political commentary with his own experiences working and living as an expat in these authoritarian states. There are strengths and limitations to this approach. Delisle isn't an investigative reporter, so his first-hand sources are mostly confined to street-level information acquired from co-workers, colleagues, friends and neighbors. But this has the advantage of making his commentary easier to absorb when the reader can observe how they affect Delisle and the ordinary people around him. During his yearlong stay in Rangoon, he accumulates a wealth a experience which he relates in vignettes composed anywhere from one page to half a dozen pages. For example, he mentions how the government literally cuts out offending material in foreign publications. He reveals that he lives near the home of celebrated opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and how she is referred to only as The Lady by the general population. He mentions seeing a Marilyn Manson t-shirt when out shopping, but that fans have to go to neighboring Thailand to buy his music recordings. He discusses the technical difficulties getting internet access when there are only two ISPs in the entire country: "...One belongs to a government minister, the other to his son.” All these anecdotes build-up to a picture of Burma as a country that despite its international isolation, its citizens are aware that they are being manipulated and have adjusted their behavior accordingly to deal with living inside a police state.* As with Pyongyang, Delisle conveys all this with his usual humorous and disaffected tone combined with an accessible drawing style which economically conveys actions, information and quick impressions to the reader.

One complaint I had with Pyongyang was that Delisle the character was never able to connect with the local population in any meaningful way. This could be explained by both the state's particularly hash form of totalitarianism and the nature of his job. But Delisle himself contributed to the problem with his own lassitude and sense of detachment. Delisle starts off being similarly ensconced within his expat bubble. He spends much of the early part of the book dealing with how his family settled into their new routine. As the book progresses, Delisle's world expands beyond his family, work colleagues, his fellow expats. He forms associations with local Burmese, particularly the community of Burmese cartoonists. He even begins to teach animation to some of them. The scope of the book also expands beyond seeing the country in purely political terms as Delisle takes a slightly bemused look at Burmese customs: from the incessant betel-chewing to the place Buddhism has in its culture. He also recounts through wordless interludes the various vacations he and his wife took during their stay. as a result, Burma Chronicles is far more rambling and episodic than Pyongyang. And some vignettes are more effective than others. While the political situation informs the entire book, it's obvious that this is primarily a memoir about Delisle's time in Burma.

This intersection between the personal and the political impacts the story in certain ways. The first is that for all the familiarity he develops with the local environment, Delisle remains a foreign visitor - namely a person from an affluent Western liberal democracy who can theoretically leave any time the situation becomes unpleasant. This is what actually happens towards the end as the junta makes the MSF mission virtually impossible to carry out.** Delisle travels to Burma secure in the knowledge that Nadège's position is just as temporary as all her previous MSF postings, and the reader naturally assumes that Delisle will come out of it more or less intact if he is to complete this book. The laid-back mood that permeates his travelogues keeps the reader at a slight distance from both the difficulties encountered within the host country, and Delisle himself.

The second is that even though Delisle gets to socialize with many Burmese in a more informal manner than with the North Koreans in Pyongyang, the book is unusually circumspect about them. He only directly names a few ordinary Burmese citizens, mainly his household staff. None of them are fleshed-out as his fellow expats. This inequality is a quite glaring omission in the book. The most generous interpretation of this is suggested by one incident: Delisle's of-the-cuff remarks to a visiting journalist come back to bite him when one of his animation students, a government employee, vanishes with no explanation. Delisle never feels like he's in danger. But he suspects that the student was punished for being associated with him. No one who makes critical remarks about the regime is ever identified within the book.

And this is where Burma Chronicles leaves the reader. It's entertaining and informative. It's not as forthright as a journalistic expose. Nor is it quite as intimate as it implies it could have been. But it's a tantalizing glimpse into a place that is little understood by many people from Delisle's background.

___

* On a personal note, the local conditions of Burma described in this book remind me of the Philippines under the Martial Law years, combined with the added burden of its pariah state status.

** In one of the more interesting conversations that Delisle records, an MSF employee offers several, not always flattering, explanations on why other international NGOs continue to work in Burma.

7/05/2009

What The F#@k is Going On in Pyongyang?

|

| Pyongyang by Guy Delisle |

North Korea launched seven ballistic missiles into waters off its east coast Saturday in a show of military firepower that defied U.N. resolutions and drew international condemnation and concern. It also fired four short-range missiles Thursday believed to be cruise missiles.

South Korea's Yonhap news agency -- citing a South Korean government source it did not identify -- reported that five of the seven ballistic missiles landed in the same area, indicating their accuracy has improved.

- KELLY OLSEN Associated Press

1/01/2009

Journey Into The Heart of The Otaku

Of course to think that manga and transsexual otakus are somehow more authentic than temples is wrongheaded, but this actually was our Japan, and we liked it here.

- Peter Carey

Happy New Year. Today I'm going to look at two very different travel memoirs about Japan that I read back-to-back during the holidays. Their only obvious similarity is that they exploit mainstream America's fascination of, and ignorance over, anime/manga as a jumping-off point for exploring Japanese culture. Be warned that examining the two together could induce whiplash.

In Wrong about Japan: A Father's Journey with His Son Booker Prize winning novelist Peter Carey and his twelve year old son Charley take a brief trip to Japan. Fascinated by Charley's new obsession with manga and anime, Carey uses his literary contacts to arrange meetings with some of Japan's leading creators. Charley wants to get his photo taken with some of his heroes, while Carey hopes to bond with his son during the trip. But he is also interested in discovering the connection between manga and anime to traditional Japanese culture. He develops a number of theories which he unsuccessfully attempts to confirm in his creator interviews.

Carey proudly admits to being a poor reporter: He's not good at remembering names. Unable to speak Japanese, he conducts his interviews by submitting a list of questions beforehand. These are usually so inept that they are brushed aside by his subjects, and he fails to ask follow-up questions. Carey is forced to to step back and admit that he's only grown more perplexed by his inability to understand the Japanese mind.

Based on the various anime and manga Carey's consumed, the history of Japan can be mapped from its feudal era, the opening of the country by Commodore Matthew Perry, World War II, the Hiroshima bombing, and the post-war recovery. His ideas don't sound unreasonable, but his overanalyzing leads him to jump to hasty conclusions. For example he learns that saya is Japanese for sword sheath. Therefore Saya, the katana wielding heroine of Blood The Last Vampire, is synonymous to sword sheath. But a colleague rebuffs this as being too obvious meaning for most Japanese. The interviewees seem mostly put-off by his theorizing. During a meeting with a famous swordsmith, his queries about the supposedly mystical nature of his craft are impatiently dismissed with matter-of-the-fact answers. When he asks Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino about what possible symbolism inspired him to use giant robots, Tomino points out that the robots were simply there to sell toys to children.

This isn't to say Carey doesn't learn a thing or two. Tomino claims to have been interested in removing all specific national elements from Gundam. When Carey insists there must still be some Japanese elements left over, Tomino (or the translator) counters "that there is maybe something in your own character which is interested in national identity." The writer of the franchise's massive official guide insists that the cockpit of the mobile suit isn't the belly of the beast as Carey thought, but is more like a mother's womb. Fans of Neon Genesis Evangelion are already familiar with that idea. His only truly successful exchange is with a survivor of the Tokyo firebombing raids, which helps reinforce the popular onscreen image of national suffering found in the wartime drama Grave of the Fireflies.

This isn't to say Carey doesn't learn a thing or two. Tomino claims to have been interested in removing all specific national elements from Gundam. When Carey insists there must still be some Japanese elements left over, Tomino (or the translator) counters "that there is maybe something in your own character which is interested in national identity." The writer of the franchise's massive official guide insists that the cockpit of the mobile suit isn't the belly of the beast as Carey thought, but is more like a mother's womb. Fans of Neon Genesis Evangelion are already familiar with that idea. His only truly successful exchange is with a survivor of the Tokyo firebombing raids, which helps reinforce the popular onscreen image of national suffering found in the wartime drama Grave of the Fireflies. Unfortunately Carey's failure to find clear answers to all his earnest questioning leads to an even bigger failure to appreciate the nebulous nature of language and culture. For someone who deals in words this is a pretty big failure. Learning many of the different definitions of the term otaku, he uses this as an example of how unique and baffling Japanese culture can be. Really? Is the Japanese language the only language that contains difficult-to-define terms with meanings that can change over time? Carey's too smart to use the word, but he is basically reinforcing the old idea of Japan as "inscrutable." Japanese nativists everywhere must be delirious with his observations.

At the heart of book is Carey's relationship with Charley. As the sullen, passive adolescent that Carey is attempting to get closer to, his failure to get manga and anime mirrors the generational gap between him and his son. Carey views Japan through the lens of its more traditional image: The Japan of temples, ukiyo-e paintings, and haiku. Carey's cluelessness apparently stems from his difficulty appreciating popular culture in general*, let alone one particularly obsessive subculture. His son on the other hand accepts manga and anime on it's own terms. He also has a grasp of modern technology that completely escapes his father. Watching him successfully navigate the labyrinth of Tokyo's subway systen, Carey comments with a litte bit of awe "You're a different species." Charley responds "We've mutated."**

Charley makes Carey promise before the trip not to show him the "Real Japan" - His words for traditional Japan. Carey breaks that promise once by forcing him to attend a kabuki performance, which Charley later declares the worst four hours of his life. Not surprisingly Charley opposes Carey's pedagogical attempts to introduce a little bit of "culture" into the proceedings. Oh boy! His father must be sooooooo proud of him. To be fair he is at that rebellious stage in his life. But Charley doesn't help himself by behaving like a stereotypically insular fanboy.

Charley is the uncommunicative type. He's unable or unwilling to express what he likes about manga and anime. He shows no interest in asking questions during the interviews conducted by Carey. While he may be the driving force behind the trip, as a character he's a black hole. This may be the reason why Carey creates a fictional friend for Charley to interact with called Takashi. He is an ethereal presence, materializing unexpectedly when something is needed to spice-up the narrative. He provides a more vocal adolescent viewpoint, guiding Carey and Charley through the streets of Akihabara and other youth hangouts.

The gap between the high-minded literary father, and his pop culture consuming son is never convincingly bridged during such a short trip, and this colors Carey's experiences about Japan. Perhaps if Carey were less overbearing and Charley were more engaging or articulate, this might have proved to be a more entertaining experience for Carey and the reader.

As the Chip Kidd designed cover clues as in, Wrong About Japan is about two males exploring animated worlds mostly full of action, violence and war. In complete contrast, the cover to Japan Ai: A Tall Girl’s Adventures in Japan implies that one is about to step into a world populated by cudly, mostly female characters. It is unapologetically in-your-face-girly: Pink is the predominant color scheme. Ball-jointed dolls and cosplay fashion are the main talking points. There are some cute little design touches such as printing the respective heights of the production staff next to their names in the book's credits page.

One important difference from the former book is that this is a comics-style illustrated travelogue. Aimee Major Steinberger is a professional animator and is completely comfortable using images to convey information or a narrative. She draws in the slick linear style that is to be expected from an experienced animator, which she is capable of modulating into more complex realism as the need arises. Steinberger draws mostly intimate scenes, and she has the good eye for detail necessary for a effective travel journal. She draws mostly in black and white, but introduces color when appropriate to capturing the local ambience of a place.

Steinberger is also a doll enthusiast who has written articles for Haute Doll magazine. When the Japanese doll company Volks invites her to visit their headquarters in Tokyo, she readily accepts, and gets two of her otaku friends to accompany her. Her visit's itinerary starts in Kyoto, makes a side trip to Takarazuka, and ends in Tokyo. Every activity is fan-oriented in some way. While the visit to Kyoto's temples and shrines may not seem particularly otaku-centric, Steinberger's views of traditional Japan have been colored by her exposure to various manga and anime. She's aware of mikos (shrine maidens) because of manga like Sailor Moon. The trio visit an onsen (hot spring bath) because almost every manga or anime character has spent time at an onsen at some point.

Steinberger is also a doll enthusiast who has written articles for Haute Doll magazine. When the Japanese doll company Volks invites her to visit their headquarters in Tokyo, she readily accepts, and gets two of her otaku friends to accompany her. Her visit's itinerary starts in Kyoto, makes a side trip to Takarazuka, and ends in Tokyo. Every activity is fan-oriented in some way. While the visit to Kyoto's temples and shrines may not seem particularly otaku-centric, Steinberger's views of traditional Japan have been colored by her exposure to various manga and anime. She's aware of mikos (shrine maidens) because of manga like Sailor Moon. The trio visit an onsen (hot spring bath) because almost every manga or anime character has spent time at an onsen at some point. Takarazuka is known for the Takarazuka Revue - An all-female musical theater company not only known for their staging of more conventional works, but also for their adaptations of various shojo manga. Steinberger manages to catch a showing of The Rose of Versailles. Despite (or maybe because of) her inability to understand a single word, she and her friends are moved to tears. Later they go to a salon that dresses their customers in costume to resemble their favorite on-stage characters.

Tokyo is naturally the highlight of the trip. Steinberger and her friends engage in a wide variety of otaku-related activities, including cosplaying at Harajuku. The trip concludes at Volks offices with a surreal ceremony performed for every owner who orders a custom-made doll from the company.

Being a six-foot tall American, Steinberger is aware of how much she and her friends stick-out, and she's willing to play the part of the good tourist while in Japan. The book is full of good humored reporting of the sites they see, the strange things they encounter, the food they eat, and the little misadventures they have due to not being able to read the signs of the local transit systems.

Being a six-foot tall American, Steinberger is aware of how much she and her friends stick-out, and she's willing to play the part of the good tourist while in Japan. The book is full of good humored reporting of the sites they see, the strange things they encounter, the food they eat, and the little misadventures they have due to not being able to read the signs of the local transit systems. Steinberger has no difficulty characterizing her entire visit as mediated through the lens of manga and anime. She neither claims to know or understand the "Real Japan," and she's perfectly unselfconscious about how much a fangirl she is. You'd have to be a cosplayer. It doesn't matter what country you're in: Dressing-up in costume and parading around in public will get you some strange looks. She's honest in admitting that the response from some of the people on the street seeing a freakishly large foreigner bedecked in gothic lolita wasn't always favorable. But her experiences have not dimmed her appreciation of otaku culture. If anything her trip just affirms that she's right to be comfortable in her own skin.

Because of her familiarity with the otaku subculture, Steinberger seems to have very little trouble adapting to her surroundings. A more cynical reader would observe that her enjoyment would last as long as she stayed in the otaku bubble. Once the novelty wore off and she leaves the bubble, culture shock would set in. True, but Steinberger doesn't claim to be anything more than a very observant traveller and a very enthusiastic geek who just happens to like the same things the Japanese like.

--------

* Carey lost me when he called Walt Disney a merely successful artist, as opposed to a truly great artist like Hayao Miyazaki.

** Given that the Carey family lives in New York, Charley's performance shouldn't come as a complete suprise.

5/26/2008

The Other: Stories from Closed-off Places

One factor contributing to the respectability of the comics medium is subject-matter. When Art Spiegelman's opus Maus: A Survivor's Tale won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, it prompted the expected round of "comics grow up" articles from the mainstream press. This was a comic that had the audacity to depict the Nazi Holocaust by drawing its characters as anthropomorphized animals. Although the novelty of the graphic novel has since faded, it's no longer unusual for news publications to include comic book reviews, especially if the book's subject-matter is considered weighty enough to warrant serious attention. Today I'm going to examine two such works that attempt to lift the veil behind authoritarian states that have already received considerable media coverage both in the past, and during the present so-called war against terror.

The Complete Persepolis

I only managed to finish Persepolis last week - the critical darling of the mainstream press from a few years back. Set in post-revolutionary Iran, it is the bildungsroman of the author Marjane Satrapi. The book made Time magazine's Best Comix of 2003 list and was awarded a prize at Angoulême. Recently it has been adapted into an animated feature. It's easy to see how this story would get the attention it did. Iran has been labeled an enemy of the West and a source of international terrorism. Satrapi has the added advantage of being an insider. At its heart the real conflict is the inner battle typical of the western-educated elite of many non-western countries: The progressive, secular world view clashing with cherished religious beliefs. An only child of a liberal Muslim family residing in Tehran in the 1980s, Satrapi's rebellion against religious authority as an impetuous teenager causes her parents to send her to Austria. But like most exiles, she's ill at ease in her new environment. The culture shock and isolation eventually get to her. She returns to Iran where she experiences reverse culture shock. At first feeling lonely and depressed, Satrapi resolves to improve herself. When she leaves Iran for the second time, she has developed into a confident, more mature woman.

On paper the author's tale of growing up in modern Iran sounds fascinating. Anything that opens the country to a world that regards it with fear and suspicion, humanizes its citizens, and provides some historical context is a commendable act. So readers are now aware that not everyone in Iran is a card carrying Muslim fanatic. Also important to the work's premise is how the age-old conflict between Arabs and Persians colors the modern-day war between Iraq and Iran. The decision to tell this story as a comic seems particularly clever. As a prose work it would have disappeared amongst all the autobiographies, but as a graphic novel it stands out as something less academic and more accessible.

All of this doesn't change my feeling that subject-matter aside, this is a rather uninspired comic. Marjane Satrapi's use of narrative captions and small panels doesn't particularly make good use of the comic medium. Indeed she doesn't have much to say about it. There's not anything particularly sophisticated about her word-image balance that would make it better than most illustrated prose. While her simple black and white art is easy to follow, it doesn't flow easily from panel to panel. Much of the pace depends on the often digressive narrative text. This lack of grasp of panel transitions makes for a rather disjointed and jerky narrative. As for her characters, while Satrapi is a good enough artist to capture the likeness of a person with a few lines, but there's still something generic about the way they move and act and speak.

Sadly, this applies to the main character of "Marji" herself. She makes for a somewhat interesting kid living in what to western eyes is unusual circumstances. But as she moves from adolescence to adulthood, she doesn't transcend the usual cliches found in coming-of-age tales. She experiences teenage alienation, takes drugs, looses her virginity, falls in love with the wrong guy, breaks-up with him, falls for another guy, gets married. The events themselves aren't the issue, but the banal manner in which they are told. I wanted to like the protagonist, but I didn't find myself caring for her when I finally put the book down. Instead I was making unfavorable comparisons to David B's much more accomplished autobiography Epileptic. This leaves me in two minds about Persepolis. On one hand I can't begrudge the success of a book. But I wouldn't recommend it as a shining example of the comics medium.

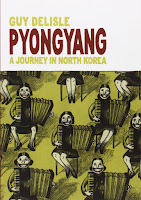

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

Pyongyang is a travelogue by Canadian Quebecois comics creator Guy Delisle. It chronicles his two month stay in that city working as a liaison between a French animation studio and the North Korean animators the company has outsourced its work to. All North Korean animators work at the state-controlled Scientific Educational Korea (SEK). During his time there, Delisle stayed in one of three hotels built to house foreign expatriate workers. He was never allowed to leave the hotel unattended. At all times he was required to be accompanied by a state-assigned guide or translator.

Right of the bat Delisle takes some self-conscious pride in being an outsider to the system. He brings a copy of George Orwell's anti-totalitarian novel 1984, noting that none of the locals seem to recognize its subversive nature. He even lends it to his translator at one point, which predictably produces an upset reaction later on. He also brings CDs of music designed to provoke the locals (reggae, jazz, and electronic music artist Aphex Twin) and even smuggles in a transistor radio - a contraband item.

Delisle is an entertaining storyteller. He's a cynical and funny observer: taking note of little details from the local fashions, to the immaculate condition of the city streets, to the ubiquitous and strangely similar portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Throughout the book he peppers his story with the kind of information accessible to him from outside of North Korea, but never shares with the locals. For example when discussing the reunification issue between North and South Korea with his translator (which he insists on calling "captain" Sin), he doesn't argue against the claim that the United States is the primary opponent to blocking reunification, but expresses his opinion to the reader that North Korea's own poverty and military build-up are a bigger obstacle to reunification. As a westerner, he is constantly aware of the of the censorship, paranoia, and repression which the North Koreans do not address. The only time he can talk freely is when he is around colleagues and other members of the expatriate community, which constitutes an island of cosmopolitanism carefully segregated from the rest of the population.

At the same time, the North Korean government never let's an opportunity to propagandize to anyone go to waste. Every weekend Delisle is invited by his guide to visit some national monument or site dedicated to the cult of Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il. he dutifully follows his guides around, but it soon gets to be too much for him. When asked by them what he thought of America after seeing a museum exhibit depicting alleged war crimes commited by American soldiers during the Korean War, Delisle makes light of those atrocities in an attempt to sound fair and balanced. They are not amused his response.

This is a significant limitation of Delisle's story. He knows how totalitarian the North Korean regime is, and wonders whether his guide and translator do: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" But they in turn seem equally convinced that Kim Il Sung is the greatest leader on Earth, and North Korea is the world's greatest nation. His inability to cross the huge gap in perception between foreigners and locals is what prevents Delisle from coming up with anything more insightful a conclusion than that ordinary North Koreans have been cowed by fear of retribution from the state - something he had already learned from Orwell. Delisle is no Joe Sacco. He's never able to penetrate the exotic strangeness of the country, or get past the ideological mask and connect with the North Koreans as individuals. I imagine that his guide and translator probably saw him as an odd and condescending westerner. But that's to be expected given the restrictions placed on him. Between the hotel and his job at the SEK, Delisle didn't have the time or the initiative to do much else. Considering these circumstances and the immensity of the cultural divide, the most he could probably ever hope to do was bond with his hosts over a good meal and a bottle of Hennessy.

The Complete Persepolis

I only managed to finish Persepolis last week - the critical darling of the mainstream press from a few years back. Set in post-revolutionary Iran, it is the bildungsroman of the author Marjane Satrapi. The book made Time magazine's Best Comix of 2003 list and was awarded a prize at Angoulême. Recently it has been adapted into an animated feature. It's easy to see how this story would get the attention it did. Iran has been labeled an enemy of the West and a source of international terrorism. Satrapi has the added advantage of being an insider. At its heart the real conflict is the inner battle typical of the western-educated elite of many non-western countries: The progressive, secular world view clashing with cherished religious beliefs. An only child of a liberal Muslim family residing in Tehran in the 1980s, Satrapi's rebellion against religious authority as an impetuous teenager causes her parents to send her to Austria. But like most exiles, she's ill at ease in her new environment. The culture shock and isolation eventually get to her. She returns to Iran where she experiences reverse culture shock. At first feeling lonely and depressed, Satrapi resolves to improve herself. When she leaves Iran for the second time, she has developed into a confident, more mature woman.

On paper the author's tale of growing up in modern Iran sounds fascinating. Anything that opens the country to a world that regards it with fear and suspicion, humanizes its citizens, and provides some historical context is a commendable act. So readers are now aware that not everyone in Iran is a card carrying Muslim fanatic. Also important to the work's premise is how the age-old conflict between Arabs and Persians colors the modern-day war between Iraq and Iran. The decision to tell this story as a comic seems particularly clever. As a prose work it would have disappeared amongst all the autobiographies, but as a graphic novel it stands out as something less academic and more accessible.

All of this doesn't change my feeling that subject-matter aside, this is a rather uninspired comic. Marjane Satrapi's use of narrative captions and small panels doesn't particularly make good use of the comic medium. Indeed she doesn't have much to say about it. There's not anything particularly sophisticated about her word-image balance that would make it better than most illustrated prose. While her simple black and white art is easy to follow, it doesn't flow easily from panel to panel. Much of the pace depends on the often digressive narrative text. This lack of grasp of panel transitions makes for a rather disjointed and jerky narrative. As for her characters, while Satrapi is a good enough artist to capture the likeness of a person with a few lines, but there's still something generic about the way they move and act and speak.

Sadly, this applies to the main character of "Marji" herself. She makes for a somewhat interesting kid living in what to western eyes is unusual circumstances. But as she moves from adolescence to adulthood, she doesn't transcend the usual cliches found in coming-of-age tales. She experiences teenage alienation, takes drugs, looses her virginity, falls in love with the wrong guy, breaks-up with him, falls for another guy, gets married. The events themselves aren't the issue, but the banal manner in which they are told. I wanted to like the protagonist, but I didn't find myself caring for her when I finally put the book down. Instead I was making unfavorable comparisons to David B's much more accomplished autobiography Epileptic. This leaves me in two minds about Persepolis. On one hand I can't begrudge the success of a book. But I wouldn't recommend it as a shining example of the comics medium.

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

Pyongyang is a travelogue by Canadian Quebecois comics creator Guy Delisle. It chronicles his two month stay in that city working as a liaison between a French animation studio and the North Korean animators the company has outsourced its work to. All North Korean animators work at the state-controlled Scientific Educational Korea (SEK). During his time there, Delisle stayed in one of three hotels built to house foreign expatriate workers. He was never allowed to leave the hotel unattended. At all times he was required to be accompanied by a state-assigned guide or translator.

Right of the bat Delisle takes some self-conscious pride in being an outsider to the system. He brings a copy of George Orwell's anti-totalitarian novel 1984, noting that none of the locals seem to recognize its subversive nature. He even lends it to his translator at one point, which predictably produces an upset reaction later on. He also brings CDs of music designed to provoke the locals (reggae, jazz, and electronic music artist Aphex Twin) and even smuggles in a transistor radio - a contraband item.

Delisle is an entertaining storyteller. He's a cynical and funny observer: taking note of little details from the local fashions, to the immaculate condition of the city streets, to the ubiquitous and strangely similar portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Throughout the book he peppers his story with the kind of information accessible to him from outside of North Korea, but never shares with the locals. For example when discussing the reunification issue between North and South Korea with his translator (which he insists on calling "captain" Sin), he doesn't argue against the claim that the United States is the primary opponent to blocking reunification, but expresses his opinion to the reader that North Korea's own poverty and military build-up are a bigger obstacle to reunification. As a westerner, he is constantly aware of the of the censorship, paranoia, and repression which the North Koreans do not address. The only time he can talk freely is when he is around colleagues and other members of the expatriate community, which constitutes an island of cosmopolitanism carefully segregated from the rest of the population.

At the same time, the North Korean government never let's an opportunity to propagandize to anyone go to waste. Every weekend Delisle is invited by his guide to visit some national monument or site dedicated to the cult of Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il. he dutifully follows his guides around, but it soon gets to be too much for him. When asked by them what he thought of America after seeing a museum exhibit depicting alleged war crimes commited by American soldiers during the Korean War, Delisle makes light of those atrocities in an attempt to sound fair and balanced. They are not amused his response.

This is a significant limitation of Delisle's story. He knows how totalitarian the North Korean regime is, and wonders whether his guide and translator do: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" But they in turn seem equally convinced that Kim Il Sung is the greatest leader on Earth, and North Korea is the world's greatest nation. His inability to cross the huge gap in perception between foreigners and locals is what prevents Delisle from coming up with anything more insightful a conclusion than that ordinary North Koreans have been cowed by fear of retribution from the state - something he had already learned from Orwell. Delisle is no Joe Sacco. He's never able to penetrate the exotic strangeness of the country, or get past the ideological mask and connect with the North Koreans as individuals. I imagine that his guide and translator probably saw him as an odd and condescending westerner. But that's to be expected given the restrictions placed on him. Between the hotel and his job at the SEK, Delisle didn't have the time or the initiative to do much else. Considering these circumstances and the immensity of the cultural divide, the most he could probably ever hope to do was bond with his hosts over a good meal and a bottle of Hennessy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)