One factor contributing to the respectability of the comics medium is subject-matter. When Art Spiegelman's opus Maus: A Survivor's Tale won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992, it prompted the expected round of "comics grow up" articles from the mainstream press. This was a comic that had the audacity to depict the Nazi Holocaust by drawing its characters as anthropomorphized animals. Although the novelty of the graphic novel has since faded, it's no longer unusual for news publications to include comic book reviews, especially if the book's subject-matter is considered weighty enough to warrant serious attention. Today I'm going to examine two such works that attempt to lift the veil behind authoritarian states that have already received considerable media coverage both in the past, and during the present so-called war against terror.

The Complete Persepolis

I only managed to finish Persepolis last week - the critical darling of the mainstream press from a few years back. Set in post-revolutionary Iran, it is the bildungsroman of the author Marjane Satrapi. The book made Time magazine's Best Comix of 2003 list and was awarded a prize at Angoulême. Recently it has been adapted into an animated feature. It's easy to see how this story would get the attention it did. Iran has been labeled an enemy of the West and a source of international terrorism. Satrapi has the added advantage of being an insider. At its heart the real conflict is the inner battle typical of the western-educated elite of many non-western countries: The progressive, secular world view clashing with cherished religious beliefs. An only child of a liberal Muslim family residing in Tehran in the 1980s, Satrapi's rebellion against religious authority as an impetuous teenager causes her parents to send her to Austria. But like most exiles, she's ill at ease in her new environment. The culture shock and isolation eventually get to her. She returns to Iran where she experiences reverse culture shock. At first feeling lonely and depressed, Satrapi resolves to improve herself. When she leaves Iran for the second time, she has developed into a confident, more mature woman.

On paper the author's tale of growing up in modern Iran sounds fascinating. Anything that opens the country to a world that regards it with fear and suspicion, humanizes its citizens, and provides some historical context is a commendable act. So readers are now aware that not everyone in Iran is a card carrying Muslim fanatic. Also important to the work's premise is how the age-old conflict between Arabs and Persians colors the modern-day war between Iraq and Iran. The decision to tell this story as a comic seems particularly clever. As a prose work it would have disappeared amongst all the autobiographies, but as a graphic novel it stands out as something less academic and more accessible.

All of this doesn't change my feeling that subject-matter aside, this is a rather uninspired comic. Marjane Satrapi's use of narrative captions and small panels doesn't particularly make good use of the comic medium. Indeed she doesn't have much to say about it. There's not anything particularly sophisticated about her word-image balance that would make it better than most illustrated prose. While her simple black and white art is easy to follow, it doesn't flow easily from panel to panel. Much of the pace depends on the often digressive narrative text. This lack of grasp of panel transitions makes for a rather disjointed and jerky narrative. As for her characters, while Satrapi is a good enough artist to capture the likeness of a person with a few lines, but there's still something generic about the way they move and act and speak.

Sadly, this applies to the main character of "Marji" herself. She makes for a somewhat interesting kid living in what to western eyes is unusual circumstances. But as she moves from adolescence to adulthood, she doesn't transcend the usual cliches found in coming-of-age tales. She experiences teenage alienation, takes drugs, looses her virginity, falls in love with the wrong guy, breaks-up with him, falls for another guy, gets married. The events themselves aren't the issue, but the banal manner in which they are told. I wanted to like the protagonist, but I didn't find myself caring for her when I finally put the book down. Instead I was making unfavorable comparisons to David B's much more accomplished autobiography Epileptic. This leaves me in two minds about Persepolis. On one hand I can't begrudge the success of a book. But I wouldn't recommend it as a shining example of the comics medium.

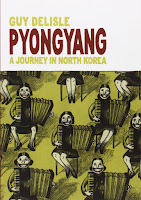

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

Pyongyang is a travelogue by Canadian Quebecois comics creator Guy Delisle. It chronicles his two month stay in that city working as a liaison between a French animation studio and the North Korean animators the company has outsourced its work to. All North Korean animators work at the state-controlled Scientific Educational Korea (SEK). During his time there, Delisle stayed in one of three hotels built to house foreign expatriate workers. He was never allowed to leave the hotel unattended. At all times he was required to be accompanied by a state-assigned guide or translator.

Right of the bat Delisle takes some self-conscious pride in being an outsider to the system. He brings a copy of George Orwell's anti-totalitarian novel 1984, noting that none of the locals seem to recognize its subversive nature. He even lends it to his translator at one point, which predictably produces an upset reaction later on. He also brings CDs of music designed to provoke the locals (reggae, jazz, and electronic music artist Aphex Twin) and even smuggles in a transistor radio - a contraband item.

Delisle is an entertaining storyteller. He's a cynical and funny observer: taking note of little details from the local fashions, to the immaculate condition of the city streets, to the ubiquitous and strangely similar portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. Throughout the book he peppers his story with the kind of information accessible to him from outside of North Korea, but never shares with the locals. For example when discussing the reunification issue between North and South Korea with his translator (which he insists on calling "captain" Sin), he doesn't argue against the claim that the United States is the primary opponent to blocking reunification, but expresses his opinion to the reader that North Korea's own poverty and military build-up are a bigger obstacle to reunification. As a westerner, he is constantly aware of the of the censorship, paranoia, and repression which the North Koreans do not address. The only time he can talk freely is when he is around colleagues and other members of the expatriate community, which constitutes an island of cosmopolitanism carefully segregated from the rest of the population.

At the same time, the North Korean government never let's an opportunity to propagandize to anyone go to waste. Every weekend Delisle is invited by his guide to visit some national monument or site dedicated to the cult of Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-Il. he dutifully follows his guides around, but it soon gets to be too much for him. When asked by them what he thought of America after seeing a museum exhibit depicting alleged war crimes commited by American soldiers during the Korean War, Delisle makes light of those atrocities in an attempt to sound fair and balanced. They are not amused his response.

This is a significant limitation of Delisle's story. He knows how totalitarian the North Korean regime is, and wonders whether his guide and translator do: "Do they really believe the bullshit that's being forced down their throats?" But they in turn seem equally convinced that Kim Il Sung is the greatest leader on Earth, and North Korea is the world's greatest nation. His inability to cross the huge gap in perception between foreigners and locals is what prevents Delisle from coming up with anything more insightful a conclusion than that ordinary North Koreans have been cowed by fear of retribution from the state - something he had already learned from Orwell. Delisle is no Joe Sacco. He's never able to penetrate the exotic strangeness of the country, or get past the ideological mask and connect with the North Koreans as individuals. I imagine that his guide and translator probably saw him as an odd and condescending westerner. But that's to be expected given the restrictions placed on him. Between the hotel and his job at the SEK, Delisle didn't have the time or the initiative to do much else. Considering these circumstances and the immensity of the cultural divide, the most he could probably ever hope to do was bond with his hosts over a good meal and a bottle of Hennessy.