By Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki.

This One Summer begins with a brief flashback of a sleeping young girl being carried by her father to a lakeside cottage. It’s a beautifully illustrated sequence that succinctly evokes that particular nostalgia for the lazy summer days of childhood: the ending of the school term, building sandcastles on the beach, feeling the heat of the sun and being blinded by the glare reflected of the water, floating on its surface or being allowing to be engulfed by its murky depths, collecting pebbles and seashells by the shore, exploring the woods and hearing the leaves underfoot being crushed, staying up late unsupervised to watch movies or swap gossip or tell scary ghost stories. Creators (and cousins) Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki certainly capture all this within their latest collaboration. But they also dig beneath the surface to fashion a story of personal growth, nascent sexuality, the inexorable dissolution of longstanding relationships, and the end of innocence. The narrative slowly unfolds through scenes composed of quiet reflection, meaningless distractions, chance meetings, short elliptical conversations, with the occasional flare-up for emphasis.

But above all else is how the story is told through stunning artwork. TOS might be the most gorgeous-looking comic book I’ve read to come out in 2014. As an illustrator Jillian is noteworthy for her lushly detailed drawing style with its varied, organic lines realized with supple brushwork. She compliments it here with delicate blue washes that work to capture the sensuality of the book’s idyllic setting. The inviting waters of the lake, the inky sky at night, the dampness of the summer rain, the quaint houses, the coolness of the shade, or the deep shadow of the verdant undergrowth. But the monochromatic color palette also serves to express a certain narrative ambiguity. The mood can subtly modulate from placid to melancholic, or from comforting to a little threatening, within an instant.

Jillian’s characters posses a slightly cartoony look that reminds me of a more nuanced version of Craig Thompson. They’re rendered with an economy of features to help distinguish them from the richly textured backgrounds. The book’s POV character is Rose, an only child who spends every summer with her parents at their residence located on the small resort town of Awago. Her usual summer companion is another girl named Windy. Based on the way Rose reminisces about them, these trips were enjoyable family vacations. But both girls are now on the cusp of adolescence, though Rose is slightly older and much lankier. While she’s beginning to notice the teenage boys around her, the cherubic Windy still views them as freaks and clings to girlish pursuits. This small contrast is mirrored in Rose’s own parents. The more stoutly built and voluble Evan seems determined that everyone have fun during their time at Awago. The introverted and tightly wound Alice is an older, more exasperated version of Rose. Her body inexplicably emaciated, her thin hair swept back and messily arranged, her face taught with worry, and the round glasses she wears form a mask which she sometimes uses to withdraw from the world.

It would be easy to blame Alice for much of the conflict that takes place in the book. And that’s what the uncomprehending Rose initially does. Events take a turn for the worse when Alice receives a visit from her vivacious sister and brother-in-law. His attempts to coax Alice out of her shell end disastrously, resulting in an impasse between Alice and Evan. This causes a rift to develop between her and Rose, heartbreakingly portrayed by their subsequent verbal exchanges in which Alice refuses to look at her daughter. The strain it puts on their relationship negatively impacts the way Rose conducts herself around other people, especially an older boy whom she's been secretly crushing on named Dunc. When a scandal involving him and his girlfriend threatens to erupt, Rose instinctively comes to his defence by formulating some unforgiving ideas about women's sexual promiscuity. This precipitates her first argument over gender politics with Windy. But this isn’t a book with any obviously labelled heroes and villains, just flawed individuals whose needs don’t always align with each other simply because they’re family. The root of Alice’s depression does eventually become discernible to the reader. And it’s a credit to Mariko’s abilities as a writer that both adults and children come across as sympathetic characters in the end.

If there’s a flaw to the book, it’s in the attempt to weave all the various plot threads by tying them together into a satisfactory conclusion. It’s the one part of the book in which the generally relaxed nature of the narrative starts to let slip some of the crinkles, and the emotional content swerves close to melodramatic territory. But this is a minor complaint when compared to the many pleasures of TOS. The book manages to distill the vivid emotions and fuzzy memories associated with the season without falling into the trap of becoming over-sentimental.

12/31/2014

12/27/2014

12/25/2014

Video: Lonely Hulk

Go to: NBC Classics

"The Lonely Man" musical theme to "The Incredible Hulk" 1978 TV series composed by Joseph "Joe" Harnell.

12/21/2014

Shoplifter

By Michael Cho

The story told in the pages of Shoplifter will be all too familiar to many: idealistic college graduate who takes a job to pay the bills, only to find herself stuck in a rut several years later. The ennui felt by the petit-bourgeois as they carry on with their humdrum routines has been grist for all kinds of popular entertainment for decades now, including many alt-lit comics from the nineties. So the graphic novel’s creator Michael Cho doesn’t exactly cover new ground here. But I suspect this trope will only continue to find an eager audience as we seemingly march towards a future in which all of human civilization has been successfully converted into a giant high-tech shopping mall, à la Wall-E.

This is a simple tale with hardly any plot to speak of. Corrina Park works as a copywriter for an ad agency located in an unnamed North American city (I’m assuming it’s Toronto). She began her career dreaming of one day becoming a novelist. But with said dreams still completely unfulfilled, her personal frustration begins to bubble to the surface. This causes her boss to inquire whether she even wants to continue working at the agency. There’s no melodrama in Shoplifter. Corinna doesn’t suddenly decide to bring down the capitalist system from within by founding an underground fight club, or anything else along those lines. But she does avail herself to a low-level form of rebellion by pilfering magazines from the local convenience store. There aren’t any illicit affairs, or physical confrontations, or office intrigue leading to a public blowout with the boss. The book is instead a quiet meditation wherein its protagonist navigates a series of mundane obstacles, culminating in a quiet epiphany. It reads like something a film school major or fledging indie director would have fashioned into a short movie. So why not adapt those devices to one's first graphic novel?

I will admit that one of the reasons I enjoyed Shoplifter is that I identified with Corrina to a considerable degree, particularly her backstory and frustrated creative ambitions. But the first words she utters, which she declares in perfect deadpan, quickly won me over. Corinna is a likeable individual. Introverted, but affable. Thoroughly dissatisfied with what she's accomplished so far, but somewhat aware of the comparable privilege she still enjoys because of her day job. Afraid of change, but desperate for personal growth. And I'm amused at how Cho draws her as a diminutive Asian woman who exhibits the occasional worry lines under her eyes. This makes her appear both fragile and visually unique. Corinna’s cropped dark hair makes her a little bit easier to spot in even the most crowded city street. But her stature constantly forces her to literally look up to anyone she engages in conversation, which is slightly comical and kinda endearing.

The supporting characters are no more than archetypes. There’s the aforementioned boss portrayed as a dapper middle-aged man who likes to put on airs. A slightly ditzy-looking receptionist co-worker, the closest person Corinna has to a friend, keeps inviting her to join in the after-hours fraternizing. A would-be love interest is given rugged good looks - complete with stubble and smouldering dark eyes. Their appearances are mercifully short, and they’re rendered in assured shorthand by Cho. He draws in a classic illustrative style along the lines of Darwyn Cooke and Jaime Hernandez. Forms and shapes are clearly delineated by eschewing cross hatching for solid shadows. Cho’s economical with his use of blacks, and employs rose pinks for midtones. The effect of these choices captures the lively bustle of the book’s urban setting and the ubiquity of electronic media.

The overarching theme of Shoplifter is how this ubiquity has allowed advertising to intrude into every aspect of our lives, influencing the way individual consumers communicate with each other until their online profiles have been turned into brands desperately promoting their status updates. Cho’s approach to the issue isn’t subtle: Corrina is seen rejecting poorly-worded proposals on an internet dating site. And the book’s pivotal scene occurs in an obnoxious nightclub party celebrating the launch of a social media site that reduces human relationships “into a plus or minus value. For whatever the client’s product or service.” Ugh! That’s so MeowMeowBeenz. But never is this more evident than in the physical world where Cho gets to show his chops as an artist and illustrator. Whether it be the conspicuously designed billboards and posters that plaster the city’s downtown area. Or the typography adorning street signs, subway station ads, train car cards, store shelf products, and magazine racks. Corrina is inundated by ad-copy wherever she goes. But as uncomfortable as that might sound, it’s lovingly realized by Cho. His urban landscapes are neatly balanced, luminous, even almost magical. The city might foster a rootless existence. But it is a seductive place, serenely insisting that the reader become lost within it.

The story told in the pages of Shoplifter will be all too familiar to many: idealistic college graduate who takes a job to pay the bills, only to find herself stuck in a rut several years later. The ennui felt by the petit-bourgeois as they carry on with their humdrum routines has been grist for all kinds of popular entertainment for decades now, including many alt-lit comics from the nineties. So the graphic novel’s creator Michael Cho doesn’t exactly cover new ground here. But I suspect this trope will only continue to find an eager audience as we seemingly march towards a future in which all of human civilization has been successfully converted into a giant high-tech shopping mall, à la Wall-E.

This is a simple tale with hardly any plot to speak of. Corrina Park works as a copywriter for an ad agency located in an unnamed North American city (I’m assuming it’s Toronto). She began her career dreaming of one day becoming a novelist. But with said dreams still completely unfulfilled, her personal frustration begins to bubble to the surface. This causes her boss to inquire whether she even wants to continue working at the agency. There’s no melodrama in Shoplifter. Corinna doesn’t suddenly decide to bring down the capitalist system from within by founding an underground fight club, or anything else along those lines. But she does avail herself to a low-level form of rebellion by pilfering magazines from the local convenience store. There aren’t any illicit affairs, or physical confrontations, or office intrigue leading to a public blowout with the boss. The book is instead a quiet meditation wherein its protagonist navigates a series of mundane obstacles, culminating in a quiet epiphany. It reads like something a film school major or fledging indie director would have fashioned into a short movie. So why not adapt those devices to one's first graphic novel?

I will admit that one of the reasons I enjoyed Shoplifter is that I identified with Corrina to a considerable degree, particularly her backstory and frustrated creative ambitions. But the first words she utters, which she declares in perfect deadpan, quickly won me over. Corinna is a likeable individual. Introverted, but affable. Thoroughly dissatisfied with what she's accomplished so far, but somewhat aware of the comparable privilege she still enjoys because of her day job. Afraid of change, but desperate for personal growth. And I'm amused at how Cho draws her as a diminutive Asian woman who exhibits the occasional worry lines under her eyes. This makes her appear both fragile and visually unique. Corinna’s cropped dark hair makes her a little bit easier to spot in even the most crowded city street. But her stature constantly forces her to literally look up to anyone she engages in conversation, which is slightly comical and kinda endearing.

The supporting characters are no more than archetypes. There’s the aforementioned boss portrayed as a dapper middle-aged man who likes to put on airs. A slightly ditzy-looking receptionist co-worker, the closest person Corinna has to a friend, keeps inviting her to join in the after-hours fraternizing. A would-be love interest is given rugged good looks - complete with stubble and smouldering dark eyes. Their appearances are mercifully short, and they’re rendered in assured shorthand by Cho. He draws in a classic illustrative style along the lines of Darwyn Cooke and Jaime Hernandez. Forms and shapes are clearly delineated by eschewing cross hatching for solid shadows. Cho’s economical with his use of blacks, and employs rose pinks for midtones. The effect of these choices captures the lively bustle of the book’s urban setting and the ubiquity of electronic media.

The overarching theme of Shoplifter is how this ubiquity has allowed advertising to intrude into every aspect of our lives, influencing the way individual consumers communicate with each other until their online profiles have been turned into brands desperately promoting their status updates. Cho’s approach to the issue isn’t subtle: Corrina is seen rejecting poorly-worded proposals on an internet dating site. And the book’s pivotal scene occurs in an obnoxious nightclub party celebrating the launch of a social media site that reduces human relationships “into a plus or minus value. For whatever the client’s product or service.” Ugh! That’s so MeowMeowBeenz. But never is this more evident than in the physical world where Cho gets to show his chops as an artist and illustrator. Whether it be the conspicuously designed billboards and posters that plaster the city’s downtown area. Or the typography adorning street signs, subway station ads, train car cards, store shelf products, and magazine racks. Corrina is inundated by ad-copy wherever she goes. But as uncomfortable as that might sound, it’s lovingly realized by Cho. His urban landscapes are neatly balanced, luminous, even almost magical. The city might foster a rootless existence. But it is a seductive place, serenely insisting that the reader become lost within it.

12/20/2014

12/17/2014

12/12/2014

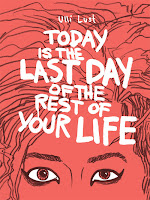

Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life

By Ulli Lust

Translated by Kim Thompson.

[this review contains spoilers]

Back in 1984, cartoonist Ulli Lust was a rebellious Austrian teenager unwilling to go down the conventional path of graduating from a good school, finding a secure job, and settling down to raise a family. So she drops out of art school, hangs out at her older sister’s Vienna apartment, and joins the punk movement - that era's fashionable counterculture. “I’m an anarchist” she proudly proclaims, “I’m going to get myself a tattoo - maybe.” Like many adolescents, she’s convinced of her own worldliness, and assured of her own personal invincibility. It doesn’t take much to persuade her to sneak into Italy with travelling companion Edi during the summer. Much of Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life is spent recounting that eventful trip. On the surface, her experience reads like a "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll” type of story. But what remains long after is the impression of hard-won knowledge about how class and gender function in the real world.

Her excursion commences with the usual high spirits. Ulli and Edi illegally cross the border into Italy on foot (needless to say, this isn’t the present-day E.U. open market) with a sleeping bag, no money or passports, and the clothes on their back. They’re relieved to be free of the oppressive atmosphere in Austria and enjoying the pleasant climate of the Italian countryside. The two soon settle into a bohemian lifestyle. As befitting their punk cred, they’re casually nihilistic - they have no problem conning money off strangers or using their femininity to get them a free meal or a place to stay for the night. Ulli does get to experience some wonderful things such as visiting some of the country’s most beautiful attractions, sleeping under the stars, swimming in the Mediterranean, attending a Clash concert, or a performance of Carmen. She and Edi meet other transients, and they receive from them a practical education on how to survive in Italy on next to nothing. Lust draws all this in a roughly-hewn style, mostly contained in the traditional grid layout and filled-in by olive-colored duotones. It looks rather unrefined at first glance, but this belies an artist fully confident in her abilities. Lust is a very capable caricaturist, easily managing her large cast of supporting and incidental characters. And she exhibits no difficulty in capturing the book’s varied and ever-changing setting, whether it be the humble backstreets of Verona or the pomp of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

But events gradually take a darker turn as the summer wanes. Ulli begins to fall into a rut as she tires of the cold and the unwanted attention of her Italian admirers. But her rejection of their advances only emboldens them further. The Virgin/Whore dichotomy found in this very masculine and Catholic-conservative culture comes to the foreground (Edi and Ulli are even explicitly described in this manner at one point). Lust’s art beautifully captures the ravenous expressions of the men who eye her and the psychological toll it takes on her, illustrated by a number of surreal fantasies. She transforms into a wraith, bursts into flame, or is engulfed in complete darkness. Ulli feels relentlessly under attack from an alien society which places far greater weight on a man’s honor than on a woman’s dignity, were any unaccompanied foreigner is viewed as fair game. Unfortunately, the pressure eventually becomes too much even for her to resist.

The advancing gloom also creates a rift between Ulli and Edi. While the two were initially linked by the yearning to escape their mundane lives back in Vienna, their opposing reactions to adversity force Ulli to confront the personal differences between them. Edi responds to the street-level violence and rampant sexism around her with wilful ignorance and extreme self-indulgence. Her craving for excitement ultimately steers the two on a self-destructive course, almost trapping them in a brutish existence under the control of Italy's more unsavoury criminal elements. This leads to the fraying of the bond between Ulli and Edi. Combined with a thousand other trivial struggles and little betrayals from other fair weather friends, and Ulli finds herself without a desperately-needed safety net. When Italy finally loses all appeal and she senses that it’s time to return to Austria, the quiet realization is deflating. “I was going to rejoin the land of the living” Ulli admits to herself.

Lust’s recollection of her youthful indiscretions is as similarly detached as the events themselves are outrageous, the voice of a self-possessed narrator looking back at her turbulent past. She’s hesitant to editorialize her actions other than deciding what to include in the book. Her older self never intrudes into the narrative to comment on, or express an opinion, let alone claim to be smarter or wiser since that time in her life. There’s no trite moralizing about her failings, and her homecoming is shorn of the cheap sentimentality expressed when a prodigal daughter is welcomed back with open arms. Ulli is instead greeted by a barrage of recriminations from her confused and exasperated parents. But battered as she is by life, her final act in the book indicates that she still retains the defiant streak that inspired her to leave home in the first place, not to mention the resilience that sustained her through tough times.

Translated by Kim Thompson.

[this review contains spoilers]

Back in 1984, cartoonist Ulli Lust was a rebellious Austrian teenager unwilling to go down the conventional path of graduating from a good school, finding a secure job, and settling down to raise a family. So she drops out of art school, hangs out at her older sister’s Vienna apartment, and joins the punk movement - that era's fashionable counterculture. “I’m an anarchist” she proudly proclaims, “I’m going to get myself a tattoo - maybe.” Like many adolescents, she’s convinced of her own worldliness, and assured of her own personal invincibility. It doesn’t take much to persuade her to sneak into Italy with travelling companion Edi during the summer. Much of Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life is spent recounting that eventful trip. On the surface, her experience reads like a "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll” type of story. But what remains long after is the impression of hard-won knowledge about how class and gender function in the real world.

Her excursion commences with the usual high spirits. Ulli and Edi illegally cross the border into Italy on foot (needless to say, this isn’t the present-day E.U. open market) with a sleeping bag, no money or passports, and the clothes on their back. They’re relieved to be free of the oppressive atmosphere in Austria and enjoying the pleasant climate of the Italian countryside. The two soon settle into a bohemian lifestyle. As befitting their punk cred, they’re casually nihilistic - they have no problem conning money off strangers or using their femininity to get them a free meal or a place to stay for the night. Ulli does get to experience some wonderful things such as visiting some of the country’s most beautiful attractions, sleeping under the stars, swimming in the Mediterranean, attending a Clash concert, or a performance of Carmen. She and Edi meet other transients, and they receive from them a practical education on how to survive in Italy on next to nothing. Lust draws all this in a roughly-hewn style, mostly contained in the traditional grid layout and filled-in by olive-colored duotones. It looks rather unrefined at first glance, but this belies an artist fully confident in her abilities. Lust is a very capable caricaturist, easily managing her large cast of supporting and incidental characters. And she exhibits no difficulty in capturing the book’s varied and ever-changing setting, whether it be the humble backstreets of Verona or the pomp of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

But events gradually take a darker turn as the summer wanes. Ulli begins to fall into a rut as she tires of the cold and the unwanted attention of her Italian admirers. But her rejection of their advances only emboldens them further. The Virgin/Whore dichotomy found in this very masculine and Catholic-conservative culture comes to the foreground (Edi and Ulli are even explicitly described in this manner at one point). Lust’s art beautifully captures the ravenous expressions of the men who eye her and the psychological toll it takes on her, illustrated by a number of surreal fantasies. She transforms into a wraith, bursts into flame, or is engulfed in complete darkness. Ulli feels relentlessly under attack from an alien society which places far greater weight on a man’s honor than on a woman’s dignity, were any unaccompanied foreigner is viewed as fair game. Unfortunately, the pressure eventually becomes too much even for her to resist.

The advancing gloom also creates a rift between Ulli and Edi. While the two were initially linked by the yearning to escape their mundane lives back in Vienna, their opposing reactions to adversity force Ulli to confront the personal differences between them. Edi responds to the street-level violence and rampant sexism around her with wilful ignorance and extreme self-indulgence. Her craving for excitement ultimately steers the two on a self-destructive course, almost trapping them in a brutish existence under the control of Italy's more unsavoury criminal elements. This leads to the fraying of the bond between Ulli and Edi. Combined with a thousand other trivial struggles and little betrayals from other fair weather friends, and Ulli finds herself without a desperately-needed safety net. When Italy finally loses all appeal and she senses that it’s time to return to Austria, the quiet realization is deflating. “I was going to rejoin the land of the living” Ulli admits to herself.

Lust’s recollection of her youthful indiscretions is as similarly detached as the events themselves are outrageous, the voice of a self-possessed narrator looking back at her turbulent past. She’s hesitant to editorialize her actions other than deciding what to include in the book. Her older self never intrudes into the narrative to comment on, or express an opinion, let alone claim to be smarter or wiser since that time in her life. There’s no trite moralizing about her failings, and her homecoming is shorn of the cheap sentimentality expressed when a prodigal daughter is welcomed back with open arms. Ulli is instead greeted by a barrage of recriminations from her confused and exasperated parents. But battered as she is by life, her final act in the book indicates that she still retains the defiant streak that inspired her to leave home in the first place, not to mention the resilience that sustained her through tough times.

12/11/2014

Webcomic: Pinocchio

Go to: Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio by KC Green

12/05/2014

11/30/2014

11/27/2014

In Real Life

By Cory Doctorow and Jen Wang.

As a YA graphic novel, In Real Life will no doubt be described by critics as being “relevant” to its target audience. Writer Cory Doctorow uses the subject of gamers and the MMORPGs (Massively Multiple Online Role-Playing Games) they play to give a crash-course on how globalization creates the conditions for economic exploitation, even within the World Wide Web. It’s a timely message, and fortunately Doctorow packages it in a form that’s both comprehensible and entertaining. Artist Jen Wang produces some beautiful illustration work in order to fashion the book’s virtual world and the characters who populate it. But the story itself suffers from a weak 3rd act. As a result, Doctorow’s thesis that the virtues of interconnectivity will save everyone comes across as less than convincing.

Anda is an American teenager inspired to participate in an MMORPG called “Coarsegold Online” and to join a guild named “Clan Fahrenheit.” The fictional Coarsegold is described as having upward of 10 million players worldwide, while Clan Farenheit is an all-female gamer group that requires its members to also play female characters. This is because women often choose to disguise themselves by playing male characters within the game as a way to guard against harassment. So the guild’s policies are designed to challenge sexist attitudes within the online world while establishing a community that provides women with much-needed support and encouragement. Sounds like a cool idea, right?

However, even Farenheit's high-minded ideals are blinkered by their own privilege. Anda is conscripted by another member named Lucy to accept real-world cash payements from shadowy clients for slaughtering playing characters dubbed “gold farmers” - individuals who hoard the game's virtual resources (gold, magic items, weapons, etc.) not for their own use, but to sell to other players, and also in return for actual cash. There's a lot of money going around that's being kept on the down-low. Lucy justifies her own mercantile behavior by claiming that gold farming is inexcusable because it violates both the rules and the laissez-faire spirit of Coarsegold. She lectures Anda on the moral superiority of players who procure resources through their own efforts, just as the game designers intended. It isn’t long before Anda is forced to confront the contradictions within Lucy’s actions, and she befriends a gold farmer named Raymond. Anda learns that he’s just one of a multitude of Chinese teenagers who work for local companies that turn a profit from gold farming. Many of them labor under sweatshop conditions. Raymond himself is suffering from poor health due to the long hours he’s required to spend online by his employer in order to earn his wage.

IRL’s narrative constantly shifts back and forth between the real and game world. Wang is equally capable rendering both. But for the most part, the real world backgrounds look nondescript while Coarsegold looks sumptuous. The game’s blend of European and East Asian artifacts appears vaguely inspired by Hayao Miyazaki. I myself find the aesthetic quite attractive. Wang doesn’t markedly change up her drawing style to help differentiate the two worlds, but she does noticeably alter her color palette. The former is dominated by deep earth tones layered by brush in translucent washes, while the latter’s colors are purer and brighter, as if to suggest the digital nature of the setting. For example, Anda’s usual hair color is brown, but within Coarsegold it burns an unrealistic hue of bright red.

Wang’s art particularly shines in the character designs, as she demonstrates a facility for facial expressions and body language expected of an animator. I like how she maintains the basic physical features of Anda and Lucy so the reader can still identify them whatever form they take. Their in-game avatars are basically fantasy projections based on their real world appearance. And all the guild members can be distinguished through their individual avatars. By contrast, Raymond and the other gold farmers share the same harmless-looking gnomelike appearance that makes them nonetheless easy to spot in a crowd. They're effectively interchangeable mascots. If anything, the subsuming of rugged individuality to a bland corporate identity (or Eastern collectivism) might be a little too on-the-nose.

But if the morale of the story is all too apparent hallway through, it at least refrains from hammering it in (That’s what Doctorow’s written introduction is for). IRL succinctly raises a whole host of thorny issues when portraying how the globalized economy functions that deserve further exploration, but then rushes to conveniently resolve them. The plot in itself is rather flimsy, with most of the secondary characters popping up just to deliver some piece of exposition. The consequence is that the comic doesn't quite convey the full weight of the problems its trying to address. Anda and Clan Fahrenheit use the power of Internet messaging to unite the gold farmers in their struggle to obtain better working conditions. But the victory feels hollow. While the newly-empowered guild celebrates in their palatial headquarters, much of the actual struggle of their Chinese counterparts takes place of-panel. The only indication the reader gets in the end is a hazy reassurance from Raymond that things are now “better” for them.

And that’s the crucial limitation of an otherwise good book. Educating its young audience and getting them engaged might be a commendable goal. The privileging of their perspective might even make them feel better about themselves. But IRL mostly leaves out of the picture those who have to toil in less fortunate conditions. It hands them another empty promise that the more affluent parts of the world will back them up next time, because openness!

As a YA graphic novel, In Real Life will no doubt be described by critics as being “relevant” to its target audience. Writer Cory Doctorow uses the subject of gamers and the MMORPGs (Massively Multiple Online Role-Playing Games) they play to give a crash-course on how globalization creates the conditions for economic exploitation, even within the World Wide Web. It’s a timely message, and fortunately Doctorow packages it in a form that’s both comprehensible and entertaining. Artist Jen Wang produces some beautiful illustration work in order to fashion the book’s virtual world and the characters who populate it. But the story itself suffers from a weak 3rd act. As a result, Doctorow’s thesis that the virtues of interconnectivity will save everyone comes across as less than convincing.

Anda is an American teenager inspired to participate in an MMORPG called “Coarsegold Online” and to join a guild named “Clan Fahrenheit.” The fictional Coarsegold is described as having upward of 10 million players worldwide, while Clan Farenheit is an all-female gamer group that requires its members to also play female characters. This is because women often choose to disguise themselves by playing male characters within the game as a way to guard against harassment. So the guild’s policies are designed to challenge sexist attitudes within the online world while establishing a community that provides women with much-needed support and encouragement. Sounds like a cool idea, right?

However, even Farenheit's high-minded ideals are blinkered by their own privilege. Anda is conscripted by another member named Lucy to accept real-world cash payements from shadowy clients for slaughtering playing characters dubbed “gold farmers” - individuals who hoard the game's virtual resources (gold, magic items, weapons, etc.) not for their own use, but to sell to other players, and also in return for actual cash. There's a lot of money going around that's being kept on the down-low. Lucy justifies her own mercantile behavior by claiming that gold farming is inexcusable because it violates both the rules and the laissez-faire spirit of Coarsegold. She lectures Anda on the moral superiority of players who procure resources through their own efforts, just as the game designers intended. It isn’t long before Anda is forced to confront the contradictions within Lucy’s actions, and she befriends a gold farmer named Raymond. Anda learns that he’s just one of a multitude of Chinese teenagers who work for local companies that turn a profit from gold farming. Many of them labor under sweatshop conditions. Raymond himself is suffering from poor health due to the long hours he’s required to spend online by his employer in order to earn his wage.

IRL’s narrative constantly shifts back and forth between the real and game world. Wang is equally capable rendering both. But for the most part, the real world backgrounds look nondescript while Coarsegold looks sumptuous. The game’s blend of European and East Asian artifacts appears vaguely inspired by Hayao Miyazaki. I myself find the aesthetic quite attractive. Wang doesn’t markedly change up her drawing style to help differentiate the two worlds, but she does noticeably alter her color palette. The former is dominated by deep earth tones layered by brush in translucent washes, while the latter’s colors are purer and brighter, as if to suggest the digital nature of the setting. For example, Anda’s usual hair color is brown, but within Coarsegold it burns an unrealistic hue of bright red.

Wang’s art particularly shines in the character designs, as she demonstrates a facility for facial expressions and body language expected of an animator. I like how she maintains the basic physical features of Anda and Lucy so the reader can still identify them whatever form they take. Their in-game avatars are basically fantasy projections based on their real world appearance. And all the guild members can be distinguished through their individual avatars. By contrast, Raymond and the other gold farmers share the same harmless-looking gnomelike appearance that makes them nonetheless easy to spot in a crowd. They're effectively interchangeable mascots. If anything, the subsuming of rugged individuality to a bland corporate identity (or Eastern collectivism) might be a little too on-the-nose.

But if the morale of the story is all too apparent hallway through, it at least refrains from hammering it in (That’s what Doctorow’s written introduction is for). IRL succinctly raises a whole host of thorny issues when portraying how the globalized economy functions that deserve further exploration, but then rushes to conveniently resolve them. The plot in itself is rather flimsy, with most of the secondary characters popping up just to deliver some piece of exposition. The consequence is that the comic doesn't quite convey the full weight of the problems its trying to address. Anda and Clan Fahrenheit use the power of Internet messaging to unite the gold farmers in their struggle to obtain better working conditions. But the victory feels hollow. While the newly-empowered guild celebrates in their palatial headquarters, much of the actual struggle of their Chinese counterparts takes place of-panel. The only indication the reader gets in the end is a hazy reassurance from Raymond that things are now “better” for them.

And that’s the crucial limitation of an otherwise good book. Educating its young audience and getting them engaged might be a commendable goal. The privileging of their perspective might even make them feel better about themselves. But IRL mostly leaves out of the picture those who have to toil in less fortunate conditions. It hands them another empty promise that the more affluent parts of the world will back them up next time, because openness!

11/21/2014

Cosplayers #1-2

Cosplayers and Cosplayers 2: Tezukon

By Dash Shaw

Cosplayers is surprisingly accessible for a Dash Shaw comic. It’s missing his requisite fantasy elements. And on first impression, it feels oddly familiar. The two books were released as pamphlets by Fantagraphics, a noticeable contrast to most of that publisher’s line of graphic novels from indie creators who've gradually abandoned the serial format over the years. Cosplayers' everyday milieu even seems to recall the listless urban settings populated by man-child heroes affecting some form of ennui found in alternative comics from the mid-nineties. But there’s a certain playfulness about our mediated reality that marks it as a Dash Shaw book.

The art is unmistakably Shaw’s unique combination of loosely drawn black-and-white line-work mixed in with computer coloring that often appears half-finished. Some panels look like basic flatwork. Others are modelled with simple two or three-color gradients. And others are filled with cheap digital effects. It might sound awful when being described, but this computer-generated form of minimalism actually reinforces the raw energy and naiveté of the comic’s mostly adolescent cast, as well as effectively speaking to their regular online activities.

A peculiar feature of the comic are the various pin-ups of random cosplayers that interrupt the narrative. The images themselves may have been copied from actual photographs. The cosplayer poses certainly have that stiff, photographic quality to them. They’re mostly portrayed floating over the kind of repeating patterns that could have been found either within the graphic software being used or downloaded from the Web. For me, this harkens back to when mainstream comics from a decade ago began to experiment with digital workflows. A lot of the coloring from the era looks rather primitive today. But a lot of artists found the new methods liberating and responded by designing page panels that were basically gratuitous pin-ups. This isn’t the case with Shaw as his art naturally subverts the usual function of the pin-up by contrasting the slick representations of these commercial properties with the less than ideal physiques of normal human beings dressing themselves in form-fitting outfits. But the digitized nature of the imagery can also refer to the pivotal role of the Web and social media in the dissemination of the cosplayer way of life.

The book’s subject-matter clearly marks it as a work that could have only been created in the 21st century. Sure, cosplay has been around almost as long as geek culture itself, but it’s become truly ubiquitous within the last several years. More importantly, it’s a form of expression favored by the current crop of fans, many of whom are women. The principle protagonists of Cosplayers are a pair of teenage girls who’re drawn together by their mutual hobby. One is an aspiring actress who dreams of fame while the other is a budding photographer who views the former as her muse. Their desire to reshape their lives with the fantasies they’ve consumed leads them to experiment with guerrilla film-making on unsuspecting strangers. It’s a dangerous task, both physically and emotionally. Not only do they risk retaliation from irate individuals not wanting to be filmed, their actions eventually open a small crack in their friendship as more people fall victim to their deception.

In the 2nd issue, the duo attends a small anime convention called “Tezukon” - in honor of the great Osamu Tezuka. While their relationship is further strained by participating in a cosplay contest followed by a chance encounter with a pair of fanboys who know them through their Youtube videos, the most memorable character is a nebbish Tezuka scholar who’s so frugal he’d rather sleep in the nearby alley and dumpster dive than pay for a hotel room. The scholar is very much a throwback to the passive, self-loathing protagonists of Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes. But he differs in one crucial respect - he actually feels awe and admiration for all the cosplayers at the convention. While there’s something creepy about a middle-aged man ogling people half his age wearing revealing costumes, his adulation is undifferentiated and an expression of envy at their youth and untapped potential. And that’s a more positive way to react to the noticeable generational shift in fan conventions.

Plus, he gets to interact with a character from another comic.

By Dash Shaw

Cosplayers is surprisingly accessible for a Dash Shaw comic. It’s missing his requisite fantasy elements. And on first impression, it feels oddly familiar. The two books were released as pamphlets by Fantagraphics, a noticeable contrast to most of that publisher’s line of graphic novels from indie creators who've gradually abandoned the serial format over the years. Cosplayers' everyday milieu even seems to recall the listless urban settings populated by man-child heroes affecting some form of ennui found in alternative comics from the mid-nineties. But there’s a certain playfulness about our mediated reality that marks it as a Dash Shaw book.

The art is unmistakably Shaw’s unique combination of loosely drawn black-and-white line-work mixed in with computer coloring that often appears half-finished. Some panels look like basic flatwork. Others are modelled with simple two or three-color gradients. And others are filled with cheap digital effects. It might sound awful when being described, but this computer-generated form of minimalism actually reinforces the raw energy and naiveté of the comic’s mostly adolescent cast, as well as effectively speaking to their regular online activities.

A peculiar feature of the comic are the various pin-ups of random cosplayers that interrupt the narrative. The images themselves may have been copied from actual photographs. The cosplayer poses certainly have that stiff, photographic quality to them. They’re mostly portrayed floating over the kind of repeating patterns that could have been found either within the graphic software being used or downloaded from the Web. For me, this harkens back to when mainstream comics from a decade ago began to experiment with digital workflows. A lot of the coloring from the era looks rather primitive today. But a lot of artists found the new methods liberating and responded by designing page panels that were basically gratuitous pin-ups. This isn’t the case with Shaw as his art naturally subverts the usual function of the pin-up by contrasting the slick representations of these commercial properties with the less than ideal physiques of normal human beings dressing themselves in form-fitting outfits. But the digitized nature of the imagery can also refer to the pivotal role of the Web and social media in the dissemination of the cosplayer way of life.

The book’s subject-matter clearly marks it as a work that could have only been created in the 21st century. Sure, cosplay has been around almost as long as geek culture itself, but it’s become truly ubiquitous within the last several years. More importantly, it’s a form of expression favored by the current crop of fans, many of whom are women. The principle protagonists of Cosplayers are a pair of teenage girls who’re drawn together by their mutual hobby. One is an aspiring actress who dreams of fame while the other is a budding photographer who views the former as her muse. Their desire to reshape their lives with the fantasies they’ve consumed leads them to experiment with guerrilla film-making on unsuspecting strangers. It’s a dangerous task, both physically and emotionally. Not only do they risk retaliation from irate individuals not wanting to be filmed, their actions eventually open a small crack in their friendship as more people fall victim to their deception.

In the 2nd issue, the duo attends a small anime convention called “Tezukon” - in honor of the great Osamu Tezuka. While their relationship is further strained by participating in a cosplay contest followed by a chance encounter with a pair of fanboys who know them through their Youtube videos, the most memorable character is a nebbish Tezuka scholar who’s so frugal he’d rather sleep in the nearby alley and dumpster dive than pay for a hotel room. The scholar is very much a throwback to the passive, self-loathing protagonists of Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes. But he differs in one crucial respect - he actually feels awe and admiration for all the cosplayers at the convention. While there’s something creepy about a middle-aged man ogling people half his age wearing revealing costumes, his adulation is undifferentiated and an expression of envy at their youth and untapped potential. And that’s a more positive way to react to the noticeable generational shift in fan conventions.

Plus, he gets to interact with a character from another comic.

11/14/2014

Animation: Landing

Go to: xkcd by Randall Munroe (via Lauren Davis)

I am sitting in my office on Earth, heart in throat & tears in my eyes. This is an amazing, astonishing, and inspiring moment. #cometlanding

— Phil Plait (@BadAstronomer) November 12, 2014

11/07/2014

Webcomic: The White Snake

Go to: Jen Wang (via Heidi MacDonald)

11/06/2014

11/01/2014

10/31/2014

Thor #1 and Chilling Adventures of Sabrina #1

Thor #1

By Jason Aaron, Russell Dauterman, Matthew Wilson, Joe Sabino, Frank Martin, Sara Pichelli, Laura Martin, Esad Ribic, Andrew Robinson, Alex Ross, Fiona Staples, Skottie Young.

Thor created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Jack Kirby.

The new status quo for the latest Thor series relaunch begins with the Asgardians assembled on the surface of the Moon to watch a moping thunder god. Having recently returned from yet another period of self-imposed exile, Odin finds his son hunched over his magic hammer Mjolnir, inexplicably no longer worthy of lifting it. His response to this sight is to blame his wife and interim leader Freyja for letting the emasculation of one of Marvel’s manliest heroes happen on her watch. This bit of dickishness being exhibited by one of the publisher’s more awful father-figures provides a not too subtle setup for the grand entrance of a much publicized, all new, unmistakably female Thor. But she only makes an appearance at the very end of the issue, so the reader’s denied the great pleasure of witnessing Odin’s horrified reaction.

What this issue does offer is a cantankerous Odin and sharp-tongued Freyja trading verbal barbs (in which she usually gets the better of the exchanges), Malekith behaving like a complete sociopath by happily tormenting a couple of mere mortals, and Thor acting depressed until he’s snapped out of his funk by the call to action. Always be the hero, even if only an unworthy one. While previous artist Esad Ribic drew in a more classic fantasy vein, Russell Dauterman finds a balance between the fantasy and superhero approach, which suits the demands of the story. His facility with faces allows him to portray perhaps the most emo version of Thor I’ve encountered in the series. And he seems comfortable recreating a variety of sci-fi and fantasy settings, whether deep space or the bottom of the ocean, immortal gods, frost giants, or killer sharks. He’s capably aided by colorist Matthew Wilson, who keeps everything bright and saturated with judicious use of a limited palette tied together by carefully shaded blues, greens, reds and yellows. Probably my favorite panel is a two-page spread portraying in dramatic panorama an army of giants attacking an undersea base, their skin faintly illuminated by the artificial lights. This is a comic of high stakes realized in the widescreen format.

Discovering someone other than Thor who can lift Mjolnir has become a bit cliched at this point. But if you don’t count alternate continuities, the candidates have all been invariably male. Writer Jason Aaron emphasizes the significance of this point through revealing some of the misogyny found within Asgardian society. Putting gender roles aside, the story does strongly imply that the new Thor is a supporting cast member who’s decided to step up to the big leagues. But unless her identity is quickly revealed next issue, this could be a form of misdirection.

Chilling Adventures of Sabrina #1

By Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, Robert Hack, Jack Morelli.

Sabrina the Teenage Witch by George Gladir, Dan DeCarlo, Rudy Lapick, Vincent DeCarlo.

Sabrina the Teenage Witch’s various media adaptations have tended to play to the Disney Channel/Nickelodean/ABC crowd through employing inoffensive tween humor. By contrast, her first appearance in the short story written by George Gladir and drawn by Dan DeCarlo portrays a character with a sinister edge to her. She’s been tasked to interfere with the lives of her fellow high school students, which she does by making them fall in love with each other, or by altering the outcome of various sporting events. As dastardly acts go, it’s still relatively innocuous stuff. But that darkness at the heart of the character forms the basis for this latest, horror-driven, reimagining of her.

Visually, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina smartly moves away from the seductive imagery of the legendary DeCarlo by using more realistically drawn figures. Robert Hack’s heavily textured surfaces and inky blotches certainly imbue the otherwise bucolic setting in an uncomfortable, claustrophobic haze, making everything look like they're covered in soot. Adding to the level of uneasiness is the intense yellow and orange color scheme. The whole story sometimes looks like it’s set on Mars, or a post-apocalyptic desert landscape. Everyone shambles around like zombies. Nothing about this world would make me want to live in it.

If I have one complaint, it’s that Hack still doesn’t have a firm grasp on the characters yet, especially the main protagonist. Sabrina’s jawline and eyes keep changing every few panels, and that’s pretty distracting.

Storywise, this issue jumps around a lot, feeling a little disjointed in places. It starts with an origin tale featuring Sabrina’s parents, followed by a montage of Sabrina’s upbringing, ending with her first day in Greendale High School. Many of the classic supporting characters are introduced from aunts Hilda and Zelda, cat familiar Salem, cousin Ambrose, school crush Harvey, and teenage rival Rosalind. In keeping with the horror angle, the witches worship Satan, practice the dark arts, and are casually cruel to mortals. Sabrina herself comes across as a mostly amoral figure with a touch of Carrie and the Anti-Christ. There’s this unexpected subplot involving two famous Riverdale characters being members of another coven that’s largely disconnected from Sabrina's narrative. But the creepy cliffhanger raises some questions as to how the supernatural is supposed to interact with the mundane world.

By Jason Aaron, Russell Dauterman, Matthew Wilson, Joe Sabino, Frank Martin, Sara Pichelli, Laura Martin, Esad Ribic, Andrew Robinson, Alex Ross, Fiona Staples, Skottie Young.

Thor created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Jack Kirby.

The new status quo for the latest Thor series relaunch begins with the Asgardians assembled on the surface of the Moon to watch a moping thunder god. Having recently returned from yet another period of self-imposed exile, Odin finds his son hunched over his magic hammer Mjolnir, inexplicably no longer worthy of lifting it. His response to this sight is to blame his wife and interim leader Freyja for letting the emasculation of one of Marvel’s manliest heroes happen on her watch. This bit of dickishness being exhibited by one of the publisher’s more awful father-figures provides a not too subtle setup for the grand entrance of a much publicized, all new, unmistakably female Thor. But she only makes an appearance at the very end of the issue, so the reader’s denied the great pleasure of witnessing Odin’s horrified reaction.

What this issue does offer is a cantankerous Odin and sharp-tongued Freyja trading verbal barbs (in which she usually gets the better of the exchanges), Malekith behaving like a complete sociopath by happily tormenting a couple of mere mortals, and Thor acting depressed until he’s snapped out of his funk by the call to action. Always be the hero, even if only an unworthy one. While previous artist Esad Ribic drew in a more classic fantasy vein, Russell Dauterman finds a balance between the fantasy and superhero approach, which suits the demands of the story. His facility with faces allows him to portray perhaps the most emo version of Thor I’ve encountered in the series. And he seems comfortable recreating a variety of sci-fi and fantasy settings, whether deep space or the bottom of the ocean, immortal gods, frost giants, or killer sharks. He’s capably aided by colorist Matthew Wilson, who keeps everything bright and saturated with judicious use of a limited palette tied together by carefully shaded blues, greens, reds and yellows. Probably my favorite panel is a two-page spread portraying in dramatic panorama an army of giants attacking an undersea base, their skin faintly illuminated by the artificial lights. This is a comic of high stakes realized in the widescreen format.

Discovering someone other than Thor who can lift Mjolnir has become a bit cliched at this point. But if you don’t count alternate continuities, the candidates have all been invariably male. Writer Jason Aaron emphasizes the significance of this point through revealing some of the misogyny found within Asgardian society. Putting gender roles aside, the story does strongly imply that the new Thor is a supporting cast member who’s decided to step up to the big leagues. But unless her identity is quickly revealed next issue, this could be a form of misdirection.

Chilling Adventures of Sabrina #1

By Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, Robert Hack, Jack Morelli.

Sabrina the Teenage Witch by George Gladir, Dan DeCarlo, Rudy Lapick, Vincent DeCarlo.

Sabrina the Teenage Witch’s various media adaptations have tended to play to the Disney Channel/Nickelodean/ABC crowd through employing inoffensive tween humor. By contrast, her first appearance in the short story written by George Gladir and drawn by Dan DeCarlo portrays a character with a sinister edge to her. She’s been tasked to interfere with the lives of her fellow high school students, which she does by making them fall in love with each other, or by altering the outcome of various sporting events. As dastardly acts go, it’s still relatively innocuous stuff. But that darkness at the heart of the character forms the basis for this latest, horror-driven, reimagining of her.

Visually, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina smartly moves away from the seductive imagery of the legendary DeCarlo by using more realistically drawn figures. Robert Hack’s heavily textured surfaces and inky blotches certainly imbue the otherwise bucolic setting in an uncomfortable, claustrophobic haze, making everything look like they're covered in soot. Adding to the level of uneasiness is the intense yellow and orange color scheme. The whole story sometimes looks like it’s set on Mars, or a post-apocalyptic desert landscape. Everyone shambles around like zombies. Nothing about this world would make me want to live in it.

If I have one complaint, it’s that Hack still doesn’t have a firm grasp on the characters yet, especially the main protagonist. Sabrina’s jawline and eyes keep changing every few panels, and that’s pretty distracting.

Storywise, this issue jumps around a lot, feeling a little disjointed in places. It starts with an origin tale featuring Sabrina’s parents, followed by a montage of Sabrina’s upbringing, ending with her first day in Greendale High School. Many of the classic supporting characters are introduced from aunts Hilda and Zelda, cat familiar Salem, cousin Ambrose, school crush Harvey, and teenage rival Rosalind. In keeping with the horror angle, the witches worship Satan, practice the dark arts, and are casually cruel to mortals. Sabrina herself comes across as a mostly amoral figure with a touch of Carrie and the Anti-Christ. There’s this unexpected subplot involving two famous Riverdale characters being members of another coven that’s largely disconnected from Sabrina's narrative. But the creepy cliffhanger raises some questions as to how the supernatural is supposed to interact with the mundane world.

10/27/2014

10/17/2014

Doctors

by Dash Shaw

The premise for Doctors would have formed the basis for an expensive, effects-laden Hollywood techno-thriller where the cast engages in spectacular battles for the fate of the world within elaborately-constructed virtual settings. There’s some interplay between the real and the illusory in these kinds of blockbusters. But for the most part, the difference between the two realms remains clear. But for an artist like Dash Shaw, such epistemological plot devices are employed to chip-away at the borders separating the land of the living and of the dead. This serves to illuminate his characters’ own pathetic experiences, desires, ambitions and fears. And this complicates the choices they make when confronted with their own mortality.

Ever the restless experimenter, Shaw’s artistic choices are designed to enhance the reader’s disorientation. Doctors is a terse graphic novel, barely under a hundred pages. Virtually every page is a vignette, which keeps the dialogue short and to the point. And each is dominated by a minimalist color overlay. On one hand this emphasizes the graphic quality of Shaw’s unadorned black and white drawings. But his selection of muted tones can often obscure its finer details. And the choice to give each page a different color overlay forces the reader to recognize the abstract nature of art and the illusory nature of the comics medium.

Towards the end, certain background details and oft-repeated patterns suddenly come to the foreground in rapid succession. There’s no clear symbolism to these objects, just a random assortment which seem to only have personal significance to the characters. It’s fragmentary, subjective, and an appropriately confounding way to end the story.

The book’s titular characters are a Doctor Cho, his daughter Tammy, and medical assistant Will. They run a clandestine business that revives the recently dead. Cho has invented a device he ironically dubs “Charon”, which allows the user to enter into the mind of the deceased (apparently confirming the mind-body dichotomy). When people die, their minds enter a kind of afterlife molded from that individual’s memories, hopes, and desires. This condition is only temporary and the mind itself will eventually “fade to black.” The trick to reviving the deceased is to convince them that the afterlife they’re experiencing isn’t real.

The story begins deceptively enough with the introduction of a wealthy widower referred to as Miss Bell. One day, she meets a young man named Mark and after a brief courtship, begins a May-December romance with him. For Bell, it sounds too good to be true. But their idyllic relationship is eventually disturbed by the presence of Bell’s daughter Laura, who begins to utter several cryptic remarks. Bell initially believes that Laura has joined some kind of religious cult. After awhile, she realizes that Laura is actually an avatar being used by the doctors to establish contact with her in the afterlife. This revelation causes her to return to consciousness. Shaw’s portrayal of her resurrection is particularly unnerving, a horrific process signalled by the zap of a defibrillator. She wakes up in a makeshift operating theater surrounding by medical equipment connected to her by various tubes and wires. The doctors inform her that it was the real Laura who had arranged for her to be brought back to life after she suffered a fatal accident.

Turns out though that resurrecting people has tragic consequences because everyone who was ever revived was just too traumatized from being torn from their afterlife to successfully return to their old self. After witnessing the toll it takes on Bell, Tammy begins to openly express her simmering doubts about the usefulness of Charon. But she’s unable to stand up to her more callous and overbearing father (whom she nicknames “Dr. No” for his ability to reject all of her requests and suggestions). Cho could care less what happens to his patients afterwards as long as new clients are lining-up to pay for his services. But has Cho bitten off more than he can chew when he agrees to help his friend Clark Gomez, a self-centered, hedonistic man who refuses to succumb to a terminal condition?

Ferrying people between life and death causes the doctors to suffer in their own way. Cho has lost all empathy and has become obsessed with controlling every aspect of his life. Tammy continually questions whether she’s even truly alive, and can only cultivate a meaningful relationship within the confines “The Sims” video game. Both have lost the ability to connect with each other and with the outside world. How can anyone remain convinced that what they experience is real when they spend so much time inside their own heads while invading the minds of others? Shaw does allow them a reconciliation of sorts. Even there, the reader is left adrift with an epilogue in which life and death cascade into one other like a recursive dream.

The premise for Doctors would have formed the basis for an expensive, effects-laden Hollywood techno-thriller where the cast engages in spectacular battles for the fate of the world within elaborately-constructed virtual settings. There’s some interplay between the real and the illusory in these kinds of blockbusters. But for the most part, the difference between the two realms remains clear. But for an artist like Dash Shaw, such epistemological plot devices are employed to chip-away at the borders separating the land of the living and of the dead. This serves to illuminate his characters’ own pathetic experiences, desires, ambitions and fears. And this complicates the choices they make when confronted with their own mortality.

Ever the restless experimenter, Shaw’s artistic choices are designed to enhance the reader’s disorientation. Doctors is a terse graphic novel, barely under a hundred pages. Virtually every page is a vignette, which keeps the dialogue short and to the point. And each is dominated by a minimalist color overlay. On one hand this emphasizes the graphic quality of Shaw’s unadorned black and white drawings. But his selection of muted tones can often obscure its finer details. And the choice to give each page a different color overlay forces the reader to recognize the abstract nature of art and the illusory nature of the comics medium.

Towards the end, certain background details and oft-repeated patterns suddenly come to the foreground in rapid succession. There’s no clear symbolism to these objects, just a random assortment which seem to only have personal significance to the characters. It’s fragmentary, subjective, and an appropriately confounding way to end the story.

The book’s titular characters are a Doctor Cho, his daughter Tammy, and medical assistant Will. They run a clandestine business that revives the recently dead. Cho has invented a device he ironically dubs “Charon”, which allows the user to enter into the mind of the deceased (apparently confirming the mind-body dichotomy). When people die, their minds enter a kind of afterlife molded from that individual’s memories, hopes, and desires. This condition is only temporary and the mind itself will eventually “fade to black.” The trick to reviving the deceased is to convince them that the afterlife they’re experiencing isn’t real.

The story begins deceptively enough with the introduction of a wealthy widower referred to as Miss Bell. One day, she meets a young man named Mark and after a brief courtship, begins a May-December romance with him. For Bell, it sounds too good to be true. But their idyllic relationship is eventually disturbed by the presence of Bell’s daughter Laura, who begins to utter several cryptic remarks. Bell initially believes that Laura has joined some kind of religious cult. After awhile, she realizes that Laura is actually an avatar being used by the doctors to establish contact with her in the afterlife. This revelation causes her to return to consciousness. Shaw’s portrayal of her resurrection is particularly unnerving, a horrific process signalled by the zap of a defibrillator. She wakes up in a makeshift operating theater surrounding by medical equipment connected to her by various tubes and wires. The doctors inform her that it was the real Laura who had arranged for her to be brought back to life after she suffered a fatal accident.

Turns out though that resurrecting people has tragic consequences because everyone who was ever revived was just too traumatized from being torn from their afterlife to successfully return to their old self. After witnessing the toll it takes on Bell, Tammy begins to openly express her simmering doubts about the usefulness of Charon. But she’s unable to stand up to her more callous and overbearing father (whom she nicknames “Dr. No” for his ability to reject all of her requests and suggestions). Cho could care less what happens to his patients afterwards as long as new clients are lining-up to pay for his services. But has Cho bitten off more than he can chew when he agrees to help his friend Clark Gomez, a self-centered, hedonistic man who refuses to succumb to a terminal condition?

Ferrying people between life and death causes the doctors to suffer in their own way. Cho has lost all empathy and has become obsessed with controlling every aspect of his life. Tammy continually questions whether she’s even truly alive, and can only cultivate a meaningful relationship within the confines “The Sims” video game. Both have lost the ability to connect with each other and with the outside world. How can anyone remain convinced that what they experience is real when they spend so much time inside their own heads while invading the minds of others? Shaw does allow them a reconciliation of sorts. Even there, the reader is left adrift with an epilogue in which life and death cascade into one other like a recursive dream.

10/08/2014

Webcomic: The Underdog Myth

Go to: Medium, by Mike Dawson (via Heidi MacDonald)

10/03/2014

Cartoon Essay: Writing People of Color

Go to: Midnight Breakfast, by MariNaomi et al.

9/26/2014

9/17/2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)