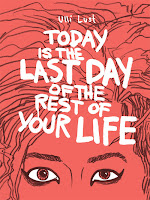

By Ulli Lust

Translated by Kim Thompson.

[this review contains spoilers]

Back in 1984, cartoonist Ulli Lust was a rebellious Austrian teenager unwilling to go down the conventional path of graduating from a good school, finding a secure job, and settling down to raise a family. So she drops out of art school, hangs out at her older sister’s Vienna apartment, and joins the punk movement - that era's fashionable counterculture. “I’m an anarchist” she proudly proclaims, “I’m going to get myself a tattoo - maybe.” Like many adolescents, she’s convinced of her own worldliness, and assured of her own personal invincibility. It doesn’t take much to persuade her to sneak into Italy with travelling companion Edi during the summer. Much of Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life is spent recounting that eventful trip. On the surface, her experience reads like a "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll” type of story. But what remains long after is the impression of hard-won knowledge about how class and gender function in the real world.

Her excursion commences with the usual high spirits. Ulli and Edi illegally cross the border into Italy on foot (needless to say, this isn’t the present-day E.U. open market) with a sleeping bag, no money or passports, and the clothes on their back. They’re relieved to be free of the oppressive atmosphere in Austria and enjoying the pleasant climate of the Italian countryside. The two soon settle into a bohemian lifestyle. As befitting their punk cred, they’re casually nihilistic - they have no problem conning money off strangers or using their femininity to get them a free meal or a place to stay for the night. Ulli does get to experience some wonderful things such as visiting some of the country’s most beautiful attractions, sleeping under the stars, swimming in the Mediterranean, attending a Clash concert, or a performance of Carmen. She and Edi meet other transients, and they receive from them a practical education on how to survive in Italy on next to nothing. Lust draws all this in a roughly-hewn style, mostly contained in the traditional grid layout and filled-in by olive-colored duotones. It looks rather unrefined at first glance, but this belies an artist fully confident in her abilities. Lust is a very capable caricaturist, easily managing her large cast of supporting and incidental characters. And she exhibits no difficulty in capturing the book’s varied and ever-changing setting, whether it be the humble backstreets of Verona or the pomp of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

But events gradually take a darker turn as the summer wanes. Ulli begins to fall into a rut as she tires of the cold and the unwanted attention of her Italian admirers. But her rejection of their advances only emboldens them further. The Virgin/Whore dichotomy found in this very masculine and Catholic-conservative culture comes to the foreground (Edi and Ulli are even explicitly described in this manner at one point). Lust’s art beautifully captures the ravenous expressions of the men who eye her and the psychological toll it takes on her, illustrated by a number of surreal fantasies. She transforms into a wraith, bursts into flame, or is engulfed in complete darkness. Ulli feels relentlessly under attack from an alien society which places far greater weight on a man’s honor than on a woman’s dignity, were any unaccompanied foreigner is viewed as fair game. Unfortunately, the pressure eventually becomes too much even for her to resist.

The advancing gloom also creates a rift between Ulli and Edi. While the two were initially linked by the yearning to escape their mundane lives back in Vienna, their opposing reactions to adversity force Ulli to confront the personal differences between them. Edi responds to the street-level violence and rampant sexism around her with wilful ignorance and extreme self-indulgence. Her craving for excitement ultimately steers the two on a self-destructive course, almost trapping them in a brutish existence under the control of Italy's more unsavoury criminal elements. This leads to the fraying of the bond between Ulli and Edi. Combined with a thousand other trivial struggles and little betrayals from other fair weather friends, and Ulli finds herself without a desperately-needed safety net. When Italy finally loses all appeal and she senses that it’s time to return to Austria, the quiet realization is deflating. “I was going to rejoin the land of the living” Ulli admits to herself.

Lust’s recollection of her youthful indiscretions is as similarly detached as the events themselves are outrageous, the voice of a self-possessed narrator looking back at her turbulent past. She’s hesitant to editorialize her actions other than deciding what to include in the book. Her older self never intrudes into the narrative to comment on, or express an opinion, let alone claim to be smarter or wiser since that time in her life. There’s no trite moralizing about her failings, and her homecoming is shorn of the cheap sentimentality expressed when a prodigal daughter is welcomed back with open arms. Ulli is instead greeted by a barrage of recriminations from her confused and exasperated parents. But battered as she is by life, her final act in the book indicates that she still retains the defiant streak that inspired her to leave home in the first place, not to mention the resilience that sustained her through tough times.