Go to: Box Brown (via Heidi MacDonald)

12/31/2015

12/30/2015

12/27/2015

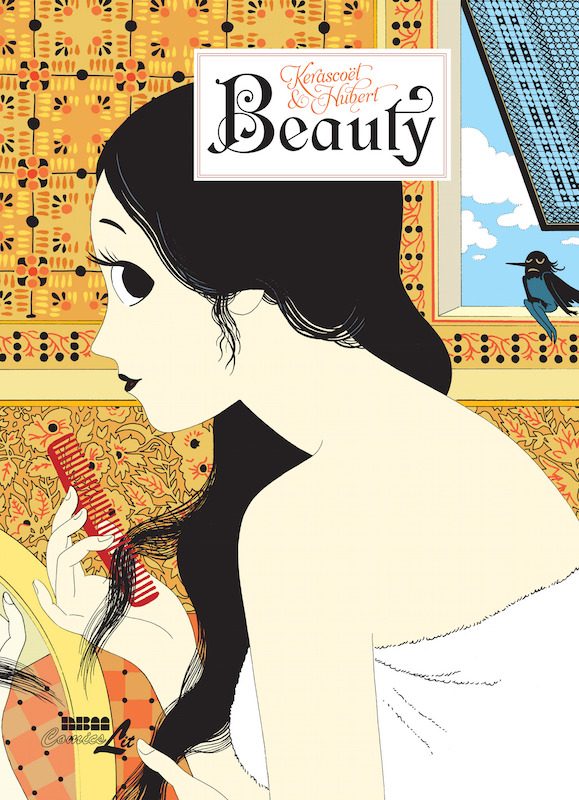

Beauty

Story: Hubert Boulard

Art: Kerascoët (Marie Pommepuy and Sébastien Cosset)

Letters: Ortho

Translation: Joe Johnson

At first glance, Beauty looks like a classic “Be careful what you wish for” story. In these type of stories, the protagonist comes to regret a wish that has come true because its fulfillment exposes terrible unforeseen consequences. Or something essential has to given up in the bargain. Or the manner in which the wish has come true was less than ideal. This usually leads to either a tragic ending, or more innocuously a successful reversal of the wish. In the latter, the hero comes away chastened by the experience. It's ultimately a genre with a conservative message. The graphic novel Seconds was a modern use of this trope. In comparison, Beauty contains more traditional elements. It starts out as a mashup of the myth of King Midas with Cinderella. But writer Hubert and husband and wife art team of Kerascoët subvert the morality of the tale and turn the wish into a catalyst for personal growth and eventually greater actualization. Though not before the experience puts our heroine through the wringer.

The comic’s setting is the pseudo-medieval Europe of most fairy tales and fantasy novels. Kerascoët brings this world to life with the characteristic use of Ligne claire, bold, flat colors, and nonlinear perspective images, neatly composed on each page as a four panel high-tiered grid. The effect is a dense visual narrative which is far more iconic than realistic. This enhances the impression of an exotic world populated by mysterious magical forces. The character designs conveniently fit into easily-recognized archetypes: the poor peasant, the handsome knight, noble king, beautiful queen, or violent warlord.

This artistic choice serves the comic’s key narrative device. The heroine is a poor, put-upon girl named Coddie who is on the verge of womanhood. One day, she inadvertently frees the fairy Mab from a magical prison and is granted one wish as a reward. Coddie wants to be beautiful, but Mab cannot change her. Instead, she imparts on Coddie a glamour which creates the illusion of beauty to whoever sets eyes on her. As such, the story is constantly shifting between Coddie’s true form and her idealized appearance. Coddie is aware of her physical imperfections every time she sees her own reflection, but this also highlights her pettiness, superficiality, and shortsightedness. To everyone else, her ethereal visage simply disarms any valid objections to her questionable behavior. Kerascoët’s art easily conveys how when even in the company of other attractive people, Coddie’s illusory charm makes her seem otherworldly in comparison.

The disadvantages of being an incarnation of the feminine ideal becomes quickly apparent when shortly after her encounter with Mab, Coddie is spotted by several of her male neighbors and they later try to gang rape her. The women react to this incident by driving Coddie out of the village. It doesn’t take long for Coddie to become a Helen of Troy object of desire as people either woo, worship, and fight for her approval. Or alternately attempt to manipulate, capture, imprison, possess, or consume her. As her legend grows, so does the chaos accompanying her until it threatens to engulf the entire kingdom.

But Coddie isn’t an impassive figure. The granting of her wish connotes an obvious sexual awakening. So she behaves like an adolescent who suddenly becomes aware of the power she holds over the opposite sex. Coddie seduces a succession of powerful men as she moves up the social ladder. But unsurprisingly, she exhibits poor judgement and self-control. And her naive understanding of love and adult relationships causes greater misery for her lovers and the people around her.

Hubert and Kerascoët infuse the story with a number of modern touches. They don’t ignore the harsh social inequalities between peasant and nobility, not to mention the patriarchal nature of the feudal system of government. As a commoner, Coddie is easily tempted by the lavish lifestyle of the aristocracy. But unlike the typical fairy tale heroine, she doesn’t live happily ever after once she marries into royalty. Two other noble women in the story are forced to treat Coddie as a rival or a threat because of the inordinate amount of influence she exerts over the men. At some point, even the peasants (or at least the peasant women) turn on her after her attempts to alleviate their suffering backfires. There’s only so much one can accomplish when being viewed more as an object than a person. While not as blunt as Game of Thrones, the book's depiction of violence and misery can be fairly graphic at times.

Indeed, everything has gone wrong for Coddie past the midway point. But where most traditional storytellers would have been content to leave off with a cautionary tale about accepting one’s limitations, this is when Coddie begins to apply the harsh lessons of her life and gradually fights back. By the end she attempts to turn the tables on her tormentors and strikes a crucial balance. The results don’t necessarily violate the rules of the comic’s fantastic milieu, but the story's concluding point is persuasively up to date.

Art: Kerascoët (Marie Pommepuy and Sébastien Cosset)

Letters: Ortho

Translation: Joe Johnson

At first glance, Beauty looks like a classic “Be careful what you wish for” story. In these type of stories, the protagonist comes to regret a wish that has come true because its fulfillment exposes terrible unforeseen consequences. Or something essential has to given up in the bargain. Or the manner in which the wish has come true was less than ideal. This usually leads to either a tragic ending, or more innocuously a successful reversal of the wish. In the latter, the hero comes away chastened by the experience. It's ultimately a genre with a conservative message. The graphic novel Seconds was a modern use of this trope. In comparison, Beauty contains more traditional elements. It starts out as a mashup of the myth of King Midas with Cinderella. But writer Hubert and husband and wife art team of Kerascoët subvert the morality of the tale and turn the wish into a catalyst for personal growth and eventually greater actualization. Though not before the experience puts our heroine through the wringer.

The comic’s setting is the pseudo-medieval Europe of most fairy tales and fantasy novels. Kerascoët brings this world to life with the characteristic use of Ligne claire, bold, flat colors, and nonlinear perspective images, neatly composed on each page as a four panel high-tiered grid. The effect is a dense visual narrative which is far more iconic than realistic. This enhances the impression of an exotic world populated by mysterious magical forces. The character designs conveniently fit into easily-recognized archetypes: the poor peasant, the handsome knight, noble king, beautiful queen, or violent warlord.

This artistic choice serves the comic’s key narrative device. The heroine is a poor, put-upon girl named Coddie who is on the verge of womanhood. One day, she inadvertently frees the fairy Mab from a magical prison and is granted one wish as a reward. Coddie wants to be beautiful, but Mab cannot change her. Instead, she imparts on Coddie a glamour which creates the illusion of beauty to whoever sets eyes on her. As such, the story is constantly shifting between Coddie’s true form and her idealized appearance. Coddie is aware of her physical imperfections every time she sees her own reflection, but this also highlights her pettiness, superficiality, and shortsightedness. To everyone else, her ethereal visage simply disarms any valid objections to her questionable behavior. Kerascoët’s art easily conveys how when even in the company of other attractive people, Coddie’s illusory charm makes her seem otherworldly in comparison.

The disadvantages of being an incarnation of the feminine ideal becomes quickly apparent when shortly after her encounter with Mab, Coddie is spotted by several of her male neighbors and they later try to gang rape her. The women react to this incident by driving Coddie out of the village. It doesn’t take long for Coddie to become a Helen of Troy object of desire as people either woo, worship, and fight for her approval. Or alternately attempt to manipulate, capture, imprison, possess, or consume her. As her legend grows, so does the chaos accompanying her until it threatens to engulf the entire kingdom.

But Coddie isn’t an impassive figure. The granting of her wish connotes an obvious sexual awakening. So she behaves like an adolescent who suddenly becomes aware of the power she holds over the opposite sex. Coddie seduces a succession of powerful men as she moves up the social ladder. But unsurprisingly, she exhibits poor judgement and self-control. And her naive understanding of love and adult relationships causes greater misery for her lovers and the people around her.

Hubert and Kerascoët infuse the story with a number of modern touches. They don’t ignore the harsh social inequalities between peasant and nobility, not to mention the patriarchal nature of the feudal system of government. As a commoner, Coddie is easily tempted by the lavish lifestyle of the aristocracy. But unlike the typical fairy tale heroine, she doesn’t live happily ever after once she marries into royalty. Two other noble women in the story are forced to treat Coddie as a rival or a threat because of the inordinate amount of influence she exerts over the men. At some point, even the peasants (or at least the peasant women) turn on her after her attempts to alleviate their suffering backfires. There’s only so much one can accomplish when being viewed more as an object than a person. While not as blunt as Game of Thrones, the book's depiction of violence and misery can be fairly graphic at times.

Indeed, everything has gone wrong for Coddie past the midway point. But where most traditional storytellers would have been content to leave off with a cautionary tale about accepting one’s limitations, this is when Coddie begins to apply the harsh lessons of her life and gradually fights back. By the end she attempts to turn the tables on her tormentors and strikes a crucial balance. The results don’t necessarily violate the rules of the comic’s fantastic milieu, but the story's concluding point is persuasively up to date.

12/25/2015

More NonSense: The Force Awakens

Off course, what's exciting to fans is the symbolic handoff of stewardship from franchise creator George Lucas to Disney. For almost forty years Lucas has steered Star Wars in accordance to his own personal dictates, both to great acclaim and heartfelt derision from fans and critics alike. He's given up ownership and responsibility for the franchise on more or less his own terms. And now Disney has just released a film with the purpose of fulfilling the deepest longings of Star Wars' most ardent worshipers by following in the steps of the Lucas of the original trilogy, while washing away the stain of the Lucas of the prequels and special editions. The fandom/religion/cult/movement had officially outgrown its founder.

As someone who saw the original trilogy during its initial theatrical run, Star Wars to me has always been synonymous with George Lucas. I'm somewhat disappointed that this occasion could have been used to make a more well-rounded appreciation of his accomplishments. But unlike some other old-timers, I've been fine with the film series continuing without him. For all its flaws, I really enjoyed TFA. Besides, a continuing Star Wars universe could use an Emo antagonist, a conscientious war objector who also happens to be black, and a kickass heroine who doesn't need anyone holding her hand. And all things considered, the original cast didn't look too bad. Face it - once TFA was in the works, the heroes of the original trilogy were probably going to lose their happy ending.

And here for your reading pleasure are a few Star Wars links:

Yours Truly:

I haven't spent a lot of time discussing the franchise on this blog, but I did write reviews for a few Star Wars books: Darth Vader and Son and Vader’s Little Princess and Star Wars: Splinter of the Mind's Eye.

Martial Arts:

How Yoda Helped to Invent Kung Fu

Can Donnie Yen Bring Kung Fu (Back) to the Star Wars Universe?

Sword vs. lightsaber: How the Samurai warrior inspired the Jedi Knights

Comics:

The Long, Complicated Relationship Between Star Wars and Marvel Comics

Popular Entertainment and Culture:

How “Star Wars” changed the world

How Star Wars Helped Create President Reagan

The Force Awakens shatters records but can it also save Hollywood?

Gender:

Why Retiring the Slave Bikini From ‘Star Wars’ is Excellent News

Please Stop Spreading This Nonsense that Rey From Star Wars Is a “Mary Sue”

“Star Wars” doesn’t have a heroine problem: Arguing over whether Rey’s a “Mary Sue” is missing the point

Some thoughts on Carrie Fisher

Race:

How Well-Meaning Tweeters Trended a Hateful Star Wars Hashtag

How 2 racist trolls got a ridiculous Star Wars boycott trending on Twitter

The Canon:

The Complete New ‘Star Wars’ Canon Timeline

A Brief History Of Star Wars Canon, Old And New

Everything We Know About Star Wars' Post-Return of the Jedi Future

What The Force Awakens Borrowed From the Old Star Wars Expanded Universe

A Not-So-Brief History of George Lucas Talking Shit About Disney’s Star Wars

George Lucas criticizes “retro” feel of new Star Wars, describes “breakup”

Not all the “Star Wars” prequels suck: Revisiting “Revenge of the Sith”

What It Would Take For ‘The Force Awakens’ To Redeem Star Wars

Kylo Ren Is Everything That Anakin Skywalker Should Have Been

The Latest Film:

Your Star Wars spoiler zone: Ars fully discusses The [REDACTED] Awakens

33 Questions We Desperately Want Answered After Star Wars: The Force Awakens

some thoughts on Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Rey

some thoughts on Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Kylo Ren

some thoughts on Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Finn

Some thoughts on Star Wars: The Force Awakens: Poe Dameron and General Hux

Pop Culture Happy Hour Small Batch: The Very Spoilery 'Star Wars'

The Nerds Talk:

Blue Milk

Stephen Colbert Explains Star Wars To Non-Fans

Weather Presenter Makes 12 Star Wars Puns In 40-Seconds

Which character is going to have the most fanfic?

The “Star Wars” fandom menace

From “A New Hope” to no hope at all

The K Chronicles: Star Wars

Tom the Dancing Bug: Chagrin Falls

12/19/2015

Racebending Iron Fist

|

| Cover excerpt from Iron Fist: The Living Weapon #1 |

This is a response to an editorial written by Alexander Lu regarding rumors about the possibility of casting of an Asian-American male to play the part of Iron Fist. Lu’s objections are understandably about not wanting to perpetuate the “Asians know martial arts” stereotype. ‘It is almost as if someone took a look at the upcoming Marvel slate and said “oh look, Iron Fist. He has martial arts skills. Perfect time to diversify casting by bringing an Asian guy in…because they are good at martial arts, right?” This train of thought speaks to how subtle and subversive cultural stereotyping can be in an era where overt racism has become much more subdued ... it is definitely not worth the perpetuation of a long beholden stereotype’ Lu proclaims. He also mentions that Iron Fist is a C-list character and any attempt to recast him as Asian won’t be greeted as cause for celebration as a major character like when Miles Morales became Spider-Man. It would be better to rally behind certain newly-minted, popular Asian American characters, such as fan-favorite Amadeus Cho.

I find this part of Lu’s argument to be his weakest point. Who’s to say that Iron Fist won’t become a more significant lead character once he makes the transition to the screen, just like other C-Listers Jason Quill, Jessica Jones, Nick Fury, or Scott Lang for that matter. They all received a huge bump in name recognition from when they were simply confined to the pages of the comics. And sure, it would be nice if Amadeus Cho and any other character originally written as Asian were to receive similar treatment instead of racebending a pre-existing character like Iron Fist or Daredevil or Spider-Man. But I’m not sure why pursuing one desirable course of action has to exclude the other? Shouldn’t all options be put on the table?

And there is a pretty good reason to fight for an Asian American Iron Fist specifically, or at least as good a reason as any. Namely it’s the very problematic nature of Danny Rand as a white savior figure. According to Lu, “When Marvel and DC Comics hear cries for diversification, their first instinct is to turn to legacy characters like Red Wolf and Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu. Even with good intentions, these heroes simply do not cut it because their histories are fraught with cultural and racial tension.” He then goes on to explain how the new Ms. Marvel - Kamala Khan, successfully uses her “heightened abilities to serve as metaphors for very human experiences– not feeling like you belong as a minority…” Well, it seems to me that an Asian American (or even a biracial) Iron Fist would not only get past the white savior trope, it could also be used to examine similar themes found in Ms. Marvel. I’m disappointed that Lu seems closed-off to those possibilities. Given that Marvel intends to produce an Iron Fist series for Netflix anyway, not asking Marvel to consider an Asian American actor to fill the role feels at the very least like ignoring the issue.

And when it comes to the issue of onscreen Asians practicing martial arts, I think this needs to be approached with more nuance than being forced to choose between the two unsavoury options of white savior or pigeonholing Asians as martial arts masters. Regarding the latter, 2015 has been a watershed year for Asian representation in the American media. It’s not perfect, but Asians are starting to break away from traditional stereotypes. These shows aren’t simply re-inventing Enter the Dragon. And any role filled by an Asian actor no longer bears the brunt of being “the one” to represent the entire Asian American community to the mainstream audience. That would include a theoretical Asian American Iron Fist series. Not everyone with an Asian background knows kung fu or karate anymore than every Caucasian knows how to box and wrestle. Martial arts are a part of the Asian cultural mileau. But the more varied and well-written the onscreen roles played by Asian talents, the less entrapping the image of the Asian martial arts master.

But the martial arts genre in the West tends to be somewhat marginalized. Like superheroes before them, the martial arts films that came out of Hollywood after the kung fu craze developed a reputation for being cheaply-made, disposable crap. And if anything can perpetuate harmful stereotypes about any race or culture, it’s the image of simplistic, poorly-conceived, incompetently produced films featuring actors sleepwalking their way through forgettable characters. Doesn't that contribute to the negativity surrounding the trope of the Asian martial arts master? With some exceptions, live-action martial arts fiction has generally faded from the small screen, which is kind of a shame since the martial arts genre is a lively component of popular Asian media, whether it’s wuxia novels, kung fu movies, or anything produced in Japan featuring ronin and ninja. Having an Asian American Iron Fist won't be enough if the series itself unquestioningly preserves some of the source material’s orientalist assumptions. The Western martial arts genre could use a bit of evolution, given added depth and richer characterization in order to deconstruct a few old-fashioned formulas and be made more relevant to a modern, diverse audience.

12/18/2015

12/17/2015

12/13/2015

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #1 & Ms. Marvel #1

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #1

Story: Brandon Montclare, Amy Reeder

Art: Natacha Bustos

Colors: Tamra Bonvillain

Letters: Travis Lanham

Covers: Amy Reeder, Trevor Von Eeden, Jeffrey Veregge

Devil Dinosaur and Moon-Boy created by Jack Kirby

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur might be the most unlikely series to come out of the All-New, All-Different Marvel. Devil Dinosaur and his erstwhile companion Moon-Boy were the late Jack Kirby’s bizarre take on the longstanding dinosaur-meets-caveman trope. Their original series was quickly cancelled, and the pair have since only made intermittent appearances in the Marvel Universe. Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder pay homage to Kirby’s ludicrous prehistoric premise, but manage to fashion the source material into a more modern kid-friendly story about a preteen hero and her unique animal companion.

Lunella Lafayette is your classic gifted, resourceful child, only with a Marvel-induced twist. Too smart for school, she’s profoundly bored with her classes. Lunella lectures her befuddled teacher and classmates about evolution being a scientific fact and not just a theory. In turn, they mockingly refer to her as “moon girl.” Basically, Lunella’s the sort of young person the publisher hopes will be reading this title. But she harbors secret fears about being an Inhuman, and she’s fascinated with collecting alien technology. “My brain is all the super-power I need” Lunella declares. One day, she stumbles upon and inadvertently activates a macguffin that forms a portal to Dinosaur World. Guess what lumbering beast emerges from the other side?

Natacha Bustos and Tamra Bonvillain illustrate a bright and saturated world, whether they’re recreating a primeval forest or present-day Manhattan. Lunella comes across as fully-realized for a new character, not to mention an unapologetic nerd. Her frantic commuting to school on roller skate shoes of her own making is adorable and somewhat reminiscent of Tony Stark’s and Peter Parker’s own inventiveness. Thankfully, Bustos doesn’t try to reproduce Kirby’s outlandish designs. Her version of Devil Dinosaur is informed by contemporary artistic interpretations of tyrannosaurs, that is if tyrannosaurs were colored crimson. His mortal enemies the Killer-Folk look and strut less like stereotypical ape-men and a bit more like long-haired modern humans wearing fur coats. That’s probably for the best since ape-men were always problematic portraits for the primitive “other.”

Ms. Marvel #1

Story: G. Willow Wilson

Art: Takeshi Miyazawa, Adrian Alphona

Colors: Ian Herring

Letters: Joe Caramagna

Covers: Cliff Chiang, John Tyler Christopher, Sara Pichelli, Justin Ponsor, Jenny Frison, Soni Balestier, Judy Stephens

Kamala Khan has had a short but acclaimed career as Ms. Marvel, so it’s a little surreal that there’s already a new Ms. Marvel #1. It’s an oddly prestigious status symbol for a character to endure several relaunches. But as with The Mighty Thor, the new series represents a return to form for the original creative team after a lengthy hiatus. The issue isn't quite as smooth a continuation of existing storylines due to corporate synergy dictating that Kamala is now an All-New, All-Different Avenger. If the previous 16 issues told of her origin tale and journey as novice superhero, the new #1 marks an upgrade in rank to marquee character.

Funnily enough, the comic immediately drops the reader into the thick of the action with Kamala fighting alongside her fellow Avengers before they’ve even officially formed in the actual Avengers title. There’s a lot going on, and the plot can often feel clunky and disjointed. Moving past her job as an Avenger, much of the story focuses on Kamala’s strained relationship with would-be love interest Bruno, who’s reacted to her rejection of his romantic overtures by beginning to date another girl. Then there’s the changing face of Jersey City, which has become a lot more blasé about the surge in supernatural activity since the debut of Ms. Marvel. And there’s a subplot involving a slimy real estate developer who’s been illegally exploiting Kamala’s likeness in his efforts to gentrify the neighborhood, which could be a shout out to real-world grassroots efforts to use her image to combat intolerance. All these threads weigh the comic down with heavy exposition, which may or may not be a deliberate move to express Kamala’s overwhelmed mood. The results are however somewhat unrefined compared to past efforts.

The last ten pages shifts the narrative voice from Kamala to Bruno, accompanied by a switch in primary artist from Takeshi Miyazawa to Adrian Alphona. Both are already proven entities, but placing their work side-by-side highlights their stylistic differences. Miyazawa draws fantastic backgrounds and strong facial expressions. They lean towards the goofy and exaggerated. Alphona’s faces are softer, and he excels in the quieter, more introspective moments. His panel-to-panel transitions are smoother. It’s also interesting to see how Ian Herring adjusts the intensity of his colors to fit the style of the artist. There's a noticeable shift towards the cooler tones for Alphona's pages.

Story: Brandon Montclare, Amy Reeder

Art: Natacha Bustos

Colors: Tamra Bonvillain

Letters: Travis Lanham

Covers: Amy Reeder, Trevor Von Eeden, Jeffrey Veregge

Devil Dinosaur and Moon-Boy created by Jack Kirby

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur might be the most unlikely series to come out of the All-New, All-Different Marvel. Devil Dinosaur and his erstwhile companion Moon-Boy were the late Jack Kirby’s bizarre take on the longstanding dinosaur-meets-caveman trope. Their original series was quickly cancelled, and the pair have since only made intermittent appearances in the Marvel Universe. Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder pay homage to Kirby’s ludicrous prehistoric premise, but manage to fashion the source material into a more modern kid-friendly story about a preteen hero and her unique animal companion.

Lunella Lafayette is your classic gifted, resourceful child, only with a Marvel-induced twist. Too smart for school, she’s profoundly bored with her classes. Lunella lectures her befuddled teacher and classmates about evolution being a scientific fact and not just a theory. In turn, they mockingly refer to her as “moon girl.” Basically, Lunella’s the sort of young person the publisher hopes will be reading this title. But she harbors secret fears about being an Inhuman, and she’s fascinated with collecting alien technology. “My brain is all the super-power I need” Lunella declares. One day, she stumbles upon and inadvertently activates a macguffin that forms a portal to Dinosaur World. Guess what lumbering beast emerges from the other side?

Natacha Bustos and Tamra Bonvillain illustrate a bright and saturated world, whether they’re recreating a primeval forest or present-day Manhattan. Lunella comes across as fully-realized for a new character, not to mention an unapologetic nerd. Her frantic commuting to school on roller skate shoes of her own making is adorable and somewhat reminiscent of Tony Stark’s and Peter Parker’s own inventiveness. Thankfully, Bustos doesn’t try to reproduce Kirby’s outlandish designs. Her version of Devil Dinosaur is informed by contemporary artistic interpretations of tyrannosaurs, that is if tyrannosaurs were colored crimson. His mortal enemies the Killer-Folk look and strut less like stereotypical ape-men and a bit more like long-haired modern humans wearing fur coats. That’s probably for the best since ape-men were always problematic portraits for the primitive “other.”

Ms. Marvel #1

Story: G. Willow Wilson

Art: Takeshi Miyazawa, Adrian Alphona

Colors: Ian Herring

Letters: Joe Caramagna

Covers: Cliff Chiang, John Tyler Christopher, Sara Pichelli, Justin Ponsor, Jenny Frison, Soni Balestier, Judy Stephens

Kamala Khan has had a short but acclaimed career as Ms. Marvel, so it’s a little surreal that there’s already a new Ms. Marvel #1. It’s an oddly prestigious status symbol for a character to endure several relaunches. But as with The Mighty Thor, the new series represents a return to form for the original creative team after a lengthy hiatus. The issue isn't quite as smooth a continuation of existing storylines due to corporate synergy dictating that Kamala is now an All-New, All-Different Avenger. If the previous 16 issues told of her origin tale and journey as novice superhero, the new #1 marks an upgrade in rank to marquee character.

Funnily enough, the comic immediately drops the reader into the thick of the action with Kamala fighting alongside her fellow Avengers before they’ve even officially formed in the actual Avengers title. There’s a lot going on, and the plot can often feel clunky and disjointed. Moving past her job as an Avenger, much of the story focuses on Kamala’s strained relationship with would-be love interest Bruno, who’s reacted to her rejection of his romantic overtures by beginning to date another girl. Then there’s the changing face of Jersey City, which has become a lot more blasé about the surge in supernatural activity since the debut of Ms. Marvel. And there’s a subplot involving a slimy real estate developer who’s been illegally exploiting Kamala’s likeness in his efforts to gentrify the neighborhood, which could be a shout out to real-world grassroots efforts to use her image to combat intolerance. All these threads weigh the comic down with heavy exposition, which may or may not be a deliberate move to express Kamala’s overwhelmed mood. The results are however somewhat unrefined compared to past efforts.

The last ten pages shifts the narrative voice from Kamala to Bruno, accompanied by a switch in primary artist from Takeshi Miyazawa to Adrian Alphona. Both are already proven entities, but placing their work side-by-side highlights their stylistic differences. Miyazawa draws fantastic backgrounds and strong facial expressions. They lean towards the goofy and exaggerated. Alphona’s faces are softer, and he excels in the quieter, more introspective moments. His panel-to-panel transitions are smoother. It’s also interesting to see how Ian Herring adjusts the intensity of his colors to fit the style of the artist. There's a noticeable shift towards the cooler tones for Alphona's pages.

12/10/2015

Video: California Christmastime

Go to: The CW, by Rachel Bloom and Vincent Rodriguez III, et al.

As someone who's spent a lot of time in Southern California, this hits close to the mark. Happy Holidays!

12/09/2015

12/05/2015

The Good Dinosaur (2015)

Directed by Peter Sohn.

Written by Bob Peterson, Kelsey Mann, Meg LeFauve.

Starring Raymond Ochoa, Jeffrey Wright, Frances McDormand, Sam Elliott.

Coming out less than five months after Inside Out, The Good Dinosaur falls into the category of minor Pixar features occupied by Cars and A Bug’s Life. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing since this effort demonstrates that the studio can also produce stories that aren’t hippy dippy psychological dramas aimed at adults. TGD possesses Pixar’s most gorgeous visuals to date, all in the service of weaving an old-fashioned coming-of-age tale designed to encourage kids to cultivate traditional values such as courage, self-reliance, or honoring the overriding importance of the nuclear family.

“Traditional” is currently a loaded word in America’s polarized political climate. Creationist/intelligent design advocates are certain to object to TGD’s pro-evolutionary stance. But the idea of an alternate timeline where dinosaurs have achieved sentience or coexist with humans is already a hoary Hollywood trope. The brightly colored, rounded geometrical designs of the dinosaurs would not look out of place in an older line-drawn or stop animation milieu. They sharply contrast with the most well-realized natural environments ever created for a Pixar feature film. The photorealism of the setting is staggering in its level of detail, especially the varied depictions of flowing water. And the expansive topography is meant to evoke the atmosphere of America’s Old West, but with dinosaurs instead of humans playing the role of homesteaders and cowboys. The humans are actually the wolves and coyotes of this imaginary world.

The ability to fabricate such carefully crafted allusions to touchstones like dinosaur/caveman stories and classic movie westerns is par for the course for the studio. Pixar has always been much more clever when it comes to integrating its popular culture references into the meat of the plot, in contrast to the more superficial humor often employed by its competitors. The reversal of humans and dinosaurs aside, Pixar doesn’t actually do anything subversive with its sources. They’re mainly mined for their sentimental value. What kid isn’t crazy about large prehistoric beasts, and what American child hasn't been inculcated to concede to the romantic allure of the Old West? A lot of the film is taken up in admiring the breathtaking vistas made possible by Pixar's talented animators and industrial-strength render farms, usually accompanied by an appropriate western-style musical soundtrack.

Not that the world-building makes any more sense than that of Cars. The film might have theropod cowboys engaged in an old-fashioned cattle drive, but there’s no context to explain its larger social significance. Sauropod dinosaurs might practice homestead farming, but there’s no reason given why that’s a better option than more primitive hunter-gathering methods. There's no evidence of the existence of towns or villages (unlike the upcoming Zootopia). Dinosaur civilization hasn’t advanced beyond stone-age technology, and even that’s made a little confusing because of their lack of opposable thumbs. As for the creatures that actually possess those attributes, it’s not clear how intelligent or how large the human population is, though they’re the only characters who wear any type of clothing. It’s best not to think about it, as the setting mainly exists to serve the story of an insecure young sauropod named Arlo (Raymond Ochoa) who becomes separated from his family after a series of unfortunate events. He finds his way home with the help of a feral boy he eventually names Spot (Jack Bright).

These two are the most prominent juvenile characters found within a Pixar story, as there are no grown-ups to share center stage with them. They come and go to either hinder or help in Arlo’s quest. The film’s episodic structure involves the two children stumbling from one dangerous situation to the next. And this starts to get repetitive after the halfway point. But the heart of the story is the developing friendship between the gangly and easily frightened Arlo, and the small but ferocious Spot as they manage to get past their interspecies-fueled distrust and forge a familial bond. It’s not particularly complicated or original for a Pixar film. So the adult fanbase might find the slow pace, simple characterizations, and dearth of witty dialogue disappointing. But the kids will have someone to relate to with Arlo. And there's that magnificent prehistoric landscape to take in.

Written by Bob Peterson, Kelsey Mann, Meg LeFauve.

Starring Raymond Ochoa, Jeffrey Wright, Frances McDormand, Sam Elliott.

Coming out less than five months after Inside Out, The Good Dinosaur falls into the category of minor Pixar features occupied by Cars and A Bug’s Life. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing since this effort demonstrates that the studio can also produce stories that aren’t hippy dippy psychological dramas aimed at adults. TGD possesses Pixar’s most gorgeous visuals to date, all in the service of weaving an old-fashioned coming-of-age tale designed to encourage kids to cultivate traditional values such as courage, self-reliance, or honoring the overriding importance of the nuclear family.

“Traditional” is currently a loaded word in America’s polarized political climate. Creationist/intelligent design advocates are certain to object to TGD’s pro-evolutionary stance. But the idea of an alternate timeline where dinosaurs have achieved sentience or coexist with humans is already a hoary Hollywood trope. The brightly colored, rounded geometrical designs of the dinosaurs would not look out of place in an older line-drawn or stop animation milieu. They sharply contrast with the most well-realized natural environments ever created for a Pixar feature film. The photorealism of the setting is staggering in its level of detail, especially the varied depictions of flowing water. And the expansive topography is meant to evoke the atmosphere of America’s Old West, but with dinosaurs instead of humans playing the role of homesteaders and cowboys. The humans are actually the wolves and coyotes of this imaginary world.

The ability to fabricate such carefully crafted allusions to touchstones like dinosaur/caveman stories and classic movie westerns is par for the course for the studio. Pixar has always been much more clever when it comes to integrating its popular culture references into the meat of the plot, in contrast to the more superficial humor often employed by its competitors. The reversal of humans and dinosaurs aside, Pixar doesn’t actually do anything subversive with its sources. They’re mainly mined for their sentimental value. What kid isn’t crazy about large prehistoric beasts, and what American child hasn't been inculcated to concede to the romantic allure of the Old West? A lot of the film is taken up in admiring the breathtaking vistas made possible by Pixar's talented animators and industrial-strength render farms, usually accompanied by an appropriate western-style musical soundtrack.

Not that the world-building makes any more sense than that of Cars. The film might have theropod cowboys engaged in an old-fashioned cattle drive, but there’s no context to explain its larger social significance. Sauropod dinosaurs might practice homestead farming, but there’s no reason given why that’s a better option than more primitive hunter-gathering methods. There's no evidence of the existence of towns or villages (unlike the upcoming Zootopia). Dinosaur civilization hasn’t advanced beyond stone-age technology, and even that’s made a little confusing because of their lack of opposable thumbs. As for the creatures that actually possess those attributes, it’s not clear how intelligent or how large the human population is, though they’re the only characters who wear any type of clothing. It’s best not to think about it, as the setting mainly exists to serve the story of an insecure young sauropod named Arlo (Raymond Ochoa) who becomes separated from his family after a series of unfortunate events. He finds his way home with the help of a feral boy he eventually names Spot (Jack Bright).

These two are the most prominent juvenile characters found within a Pixar story, as there are no grown-ups to share center stage with them. They come and go to either hinder or help in Arlo’s quest. The film’s episodic structure involves the two children stumbling from one dangerous situation to the next. And this starts to get repetitive after the halfway point. But the heart of the story is the developing friendship between the gangly and easily frightened Arlo, and the small but ferocious Spot as they manage to get past their interspecies-fueled distrust and forge a familial bond. It’s not particularly complicated or original for a Pixar film. So the adult fanbase might find the slow pace, simple characterizations, and dearth of witty dialogue disappointing. But the kids will have someone to relate to with Arlo. And there's that magnificent prehistoric landscape to take in.

11/28/2015

The Mighty Thor #1

Story: Jason Aaron

Art: Russell Dauterman

Colors: Matthew Wilson

Letters: Joe Sabino

Cover: Russell Dauterman, Matthew Wilson, Olivier Coipel, Mike Deodato, Sarah Jean Maefs, Judy Stephens

Thor created by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Jack Kirby.

Despite the #1 designation, The Mighty Thor follows up on the previous series’ final panel revelation that Thor’s longtime love interest Jane Foster had assumed the Thunder God’s mantle. More importantly, the new series retains the old creative team and the overall direction they were mapping out before being interrupted by Secret Wars. While this doesn't make it the most convenient jumping on point, there’s no lapse in quality from their work in the previous series. If anything, the team is finally settling into a comfortable groove now that the whole mystery of the new Thor’s identity has been resolved.

The issue actually feels a bit like the arrival of a Game of Thrones season premiere after a lengthy hiatus. There’s a lot to catch up on, and the story moves briskly from scene to scene. The failure of Jane’s chemotherapy treatments to stem her cancer, Thor’s evolving relationship with Earth’s superhero community, the deteriorating marriage of Odin and Freyja, the suddenly missing Odinson, the fallout from the Frost Giants retrieval of Laufey’s skull, the unholy alliance between Dario Agger and Malekith, and their secret genocidal campaign against Alfheim. Each plot point serves to increase the sense of unease as Jane’s many enemies, mundane and divine, are lining up against her.

One of the most fun things about the series is how it continues to poke fun at the more regressive features of the fantasy genre. Odin’s prejudice against the new Thor has come to negatively impact how he governs Asgardia. The realm eternal has never been a functioning democracy, but Odin’s misdirected antagonism has edged him even closer to totalitarian rule. Yet he still fails to recognize that the true enemies of his kingdom are serving it a generous helping of warmongering, corporate greed and environmental destruction, all while he imprisons or alienates its most effective protectors and hampers the efforts of its staunchest allies. If this isn’t also writer Jason Aaron making some loose reference to the demoralizing state of contemporary American politics, then what is?

What sets the overall tone for the comic is Jane’s losing battle with cancer. As she undergoes her regular treatment at a hospital, she monologues through a series of captions with almost clinical detachment the debilitating effects of chemotherapy on her mind and body. She even reveals how the enchantment of Mjolnir is actually neutralizing the chemotherapy, thus making every transformation into Thor nudge her closer to death. This sense of inevitability Aaron invokes is enhanced by the cold sterility of the hospital environment drawn by Russell Dauterman. This is the series’ first intimate look at Jane when she’s not playing thunder goddess, and it's a harrowing portrait of human fragility for a mainstream superhero comic.

But at the first sign of danger, Jane leaps into action. Her single-handed feat has her stopping a plummeting space station from crashing into the Washington DC Mall and saving everyone on board. Dauterman illustrates its physics-defying glory with his characteristic use of exploding jagged panels. He continues to excel with supernaturally-based action, and this particular issue allows him to draw more of Asgardia and the various mythological denizens of Norse mythology. But it’s the digitally rendered technicolor palette of colorist Matthew Wilson that rounds out the picture by imbuing the otherworldly setting with a warm glow, filling all negative space with mysterious, cackling magical energy.

11/25/2015

11/22/2015

All-New, All-Different Avengers #1 & All-New Wolverine #1

All-New, All-Different Avengers #1

Story: Mark Waid

Art: Adam Kubert, Mahmud Asrar

Colors: Sonia Oback, Dave McCaig

Letters: Cory Petit

Covers: Alex Ross, Mahmud Asrar, Luchiano Vecchio, Jim Cheung, Jason Keith, Cliff Chiang, David Marquez, Jack Kirby, Dick Ayers, Paul Mounts

Avengers created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

The All-New, All-Different Avengers actually splits the difference between the old and the new. On one hand, virtually every character included in this incarnation of the team is based on a well-established property who does have ties with the Avengers. But more than half the members are more recent versions created within the last few years, which helps to generate a more convincing illusion of change than past team shake-ups. Their youthfulness and diversity makes for a different kind of Avengers. Instead of the usual group of self-assured veterans, they’re a bunch of relatively inexperienced superheroes looking to establish themselves within the Marvel Universe.

Even the team’s two elder statesmen Sam Wilson (Captain America) and Tony Stark (Iron Man) introduce themselves in this issue by commiserating with each other about their current personal and financial woes affecting them within their respective solo titles. Apparently, Steve Rogers (original flavor Captain America) now hates them both. They run into Miles Morales (Spider-Man) while passing by the former Avengers Tower, only to get trounced by a powerful alien warrior. They're not exactly Earth’s Mightiest Heroes anymore.

Meanwhile at Jersey City, Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel) and Sam Alexander (Nova) team up for the first time to stop a monster from trampling one of Kamala’s favorite hangout spots. They tackle the threat easily enough, but become tongue-tied being around each other since they're both insecure teenagers and all. It’s the comic’s meet cute story.

A few core members are still outstanding by the end of the issue, and there’s still the problem of how to stop the big mean alien from tearing up New York. Jane Foster (Thor) and Vision will presumably be joining Kamala and Sam in making the trek across the river by the next issue to kick alien butt, and the new team will then be officially named. Writer Mark Waid keeps the banter light and humor-laden, and makes a reasonably fine effort in juggling the different voices of every character. Artist Adam Kubert draws some spectacular action sequences for the first part of this issue, while Mahmud Asrar mostly deals with the Kamala/Sam pairing. Asrar is a much less capable draftsperson than Kubert. But at least he’s able to convey the awkwardness of the two adolescents’ interaction.

I will however complain a little about the cover art from Alex Ross. His stiffly posed photorealism is starting to look pretty generic at this point, conveying zero personality from his subjects. And the way he illuminates his figures so they all look like they’re draped in dull satin has always been a particular weakness of his style.

All-New Wolverine #1

Story: Tom Taylor

Art: David Lopez, David Navarrot

Colors: Nathan Fairbairn

Letters: Cory Petit

Cover: Bengal, David Lopez, Art Adams, Peter Steigerwald, David Marquez, Marte Gracia, Keron Grant

Wolverine created by Roy Thomas, Len Wein, John Romita, Herb Trimpe

Laura Kinney/X-23 created by Craig Kyle and Christopher Yost

All-New Wolverine situates the reader right in the middle of the action with no explanation given, and doesn’t let off til the very last page. There’s plenty of gunfire, explosions, car chases, leaping from great heights, hand-to-hand combat, and off course the requisite slashing with adamantium laced claws. It’s kinda awesome and exactly what any reader wants out of a Wolverine comic, although a little problematic for reasons that will be shortly made clear. But as the title suggests, this isn’t Logan beneath the mask anymore but his clone/protege Laura Kinney who has taken up the mantle. And she’s not quite as crazy as the old man. As Logan admits, “You’re the best there is at what you do. But that doesn't mean you have to do it.”

A rain-drenched Paris at night functions as the backdrop for the action set piece, the evocative setting enhancing the intrigue of the story (An unfortunately timed choice, given the horror of recent real-world events). The two artists of David Lopez and David Navarrot provide a nice balance of fine detail and rough textures. They provide plenty of excitement right off the bat with a frantically staged sequence of Laura fighting her way up the Eiffel Tower in a failed bid to stop an assassination attempt. Colorist Nathan Fairbairn offsets all the gritty detail with overlays of softer tones.

While writer Tom Taylor provides little context for the action, he does squeeze in some quiet characterization through the budding romance between Laura and the teenage Warren Worthington (Angel). Witnessing Laura become grievously injured from a fiery collision into the Arc de Triomphe (Again, not the most appropriate national landmark for the hero to be wrecking at this time due to recent events that took place in real-world Paris) and unable to do anything but wait until she heals, he expresses his concern by patting her on the head. It’s the one all to brief moment of tenderness they share before the action resumes.

Story: Mark Waid

Art: Adam Kubert, Mahmud Asrar

Colors: Sonia Oback, Dave McCaig

Letters: Cory Petit

Covers: Alex Ross, Mahmud Asrar, Luchiano Vecchio, Jim Cheung, Jason Keith, Cliff Chiang, David Marquez, Jack Kirby, Dick Ayers, Paul Mounts

Avengers created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

The All-New, All-Different Avengers actually splits the difference between the old and the new. On one hand, virtually every character included in this incarnation of the team is based on a well-established property who does have ties with the Avengers. But more than half the members are more recent versions created within the last few years, which helps to generate a more convincing illusion of change than past team shake-ups. Their youthfulness and diversity makes for a different kind of Avengers. Instead of the usual group of self-assured veterans, they’re a bunch of relatively inexperienced superheroes looking to establish themselves within the Marvel Universe.

Even the team’s two elder statesmen Sam Wilson (Captain America) and Tony Stark (Iron Man) introduce themselves in this issue by commiserating with each other about their current personal and financial woes affecting them within their respective solo titles. Apparently, Steve Rogers (original flavor Captain America) now hates them both. They run into Miles Morales (Spider-Man) while passing by the former Avengers Tower, only to get trounced by a powerful alien warrior. They're not exactly Earth’s Mightiest Heroes anymore.

Meanwhile at Jersey City, Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel) and Sam Alexander (Nova) team up for the first time to stop a monster from trampling one of Kamala’s favorite hangout spots. They tackle the threat easily enough, but become tongue-tied being around each other since they're both insecure teenagers and all. It’s the comic’s meet cute story.

A few core members are still outstanding by the end of the issue, and there’s still the problem of how to stop the big mean alien from tearing up New York. Jane Foster (Thor) and Vision will presumably be joining Kamala and Sam in making the trek across the river by the next issue to kick alien butt, and the new team will then be officially named. Writer Mark Waid keeps the banter light and humor-laden, and makes a reasonably fine effort in juggling the different voices of every character. Artist Adam Kubert draws some spectacular action sequences for the first part of this issue, while Mahmud Asrar mostly deals with the Kamala/Sam pairing. Asrar is a much less capable draftsperson than Kubert. But at least he’s able to convey the awkwardness of the two adolescents’ interaction.

I will however complain a little about the cover art from Alex Ross. His stiffly posed photorealism is starting to look pretty generic at this point, conveying zero personality from his subjects. And the way he illuminates his figures so they all look like they’re draped in dull satin has always been a particular weakness of his style.

All-New Wolverine #1

Story: Tom Taylor

Art: David Lopez, David Navarrot

Colors: Nathan Fairbairn

Letters: Cory Petit

Cover: Bengal, David Lopez, Art Adams, Peter Steigerwald, David Marquez, Marte Gracia, Keron Grant

Wolverine created by Roy Thomas, Len Wein, John Romita, Herb Trimpe

Laura Kinney/X-23 created by Craig Kyle and Christopher Yost

All-New Wolverine situates the reader right in the middle of the action with no explanation given, and doesn’t let off til the very last page. There’s plenty of gunfire, explosions, car chases, leaping from great heights, hand-to-hand combat, and off course the requisite slashing with adamantium laced claws. It’s kinda awesome and exactly what any reader wants out of a Wolverine comic, although a little problematic for reasons that will be shortly made clear. But as the title suggests, this isn’t Logan beneath the mask anymore but his clone/protege Laura Kinney who has taken up the mantle. And she’s not quite as crazy as the old man. As Logan admits, “You’re the best there is at what you do. But that doesn't mean you have to do it.”

A rain-drenched Paris at night functions as the backdrop for the action set piece, the evocative setting enhancing the intrigue of the story (An unfortunately timed choice, given the horror of recent real-world events). The two artists of David Lopez and David Navarrot provide a nice balance of fine detail and rough textures. They provide plenty of excitement right off the bat with a frantically staged sequence of Laura fighting her way up the Eiffel Tower in a failed bid to stop an assassination attempt. Colorist Nathan Fairbairn offsets all the gritty detail with overlays of softer tones.

While writer Tom Taylor provides little context for the action, he does squeeze in some quiet characterization through the budding romance between Laura and the teenage Warren Worthington (Angel). Witnessing Laura become grievously injured from a fiery collision into the Arc de Triomphe (Again, not the most appropriate national landmark for the hero to be wrecking at this time due to recent events that took place in real-world Paris) and unable to do anything but wait until she heals, he expresses his concern by patting her on the head. It’s the one all to brief moment of tenderness they share before the action resumes.

11/18/2015

Martial Myths: Rousey vs Holm

|

| "Revolution" Trailer |

The fight however confirmed what every critic has said about Rousey’s stand-up: she’s a sloppy fighter with plenty of holes in her striking game. They’ve been easy to overlook because no one had exhibited the skill-set necessary to exploit them or the discipline required to counter Rousey’s trademark aggression. That was until she literally ran right into Holm’s fists. Virtually all of Rousey’s attempts to bum rush Holm resulted in her receiving a clean shot to the face. Things only got worse for Rousey because she was unable to cut off the cage. By the end of the 1st round, it was clear that her camp had not supplied Rousey with the proper tools to either beat Holm on the feet or to trap the superior striker on the ground.

But the fight also marks a step forward for WMMA. Historically, boxers have fared poorly in grappler vs. striker matchups, and while MMA itself has moved away from such strict “style vs. style” calculations, Rousey is something of a throwback to the days when pure grappling would dominate the cage. The playbook to beat that kind of fighter already exists, so it was only a matter of time until someone would implement it. Which is what Holm successfully accomplished at Melbourne on a Sunday afternoon. Holm defeated Rousey not just because she was the better boxer, she was the better all-around athlete that day. Her defensive grappling was sound. Most significantly, her upset victory was absolutely convincing. Holm just made the division a lot more interesting.

None of this changes what Rousey has already done for the sport, in raising the profile of women athletes, or her achievements as a breakout star. But as with many other celebrities, the hype accompanying her ascent was setting her up for the inevitable fall. And it doesn’t help when someone might have even started believing in their own hype. It’s certainly nowhere near the end of the Ronda Rousey brand. She’ll need to develop those missing tools if she intends to take the title back from Holm. But the loss of her invincibility opens up some new possibilities. No matter who she faces next, any successful comeback will be marketed as the redemptive arc of a grander narrative. Though whatever happens, fans now have their permanent reminder that Rousey is as human and as fallible as anyone.

11/14/2015

Love from the Shadows

by Gilbert Hernandez

cover: Steve Martinez

design: Alexa Koenings

A meta-fictional conceit of Gilbert Hernandez’s standalone “Fritz” stories is that Rosalba “Fritz” Martinez, one of the more popular recurring characters from his Palomar series, once starred in a bunch of godawful B-movies. By adapting these movies into a growing collection of graphic novels, Gilbert can capitalize on the pre-existing appeal of this tragic, top-heavy bombshell of a figure while working on the pretense that these are new characters operating under completely different circumstances. Fritz has long been notorious for her outrageous combination of high intelligence, a voluptuous physique, light skin, voracious sexual appetite, and speaking with a “high soft lisp”, which has been alternately treated by the people around her as either endearing or deeply annoying. But she’s also been a victim of abuse at the hands of her past sexual partners, numbing the pain with bouts of heavy drinking. Love from the Shadows exploits many of those traits in Fritz’s most bravura performance and a perverse, violent, bizarre tale. I can’t really say if this is a good comic, let alone if the movie it’s pretending to be based on is worth watching. But it is strangely compelling.

And as an apparent rebuke to those fans who’ve dismissed Gilbert for his particular propensity for drawing buxom women, the graphic novel’s cover is his most confrontational yet. Painted by Steve Martinez, the pulpy, lurid quality of the bikini-clad pin-up lounging on a beach next to the ominous shadow of an unseen individual hovering behind her promises to supply all the cheap thrills expected of a clunky matinee movie, not to mention satisfy the reader’s prurient interests. It probably helps catch the eye of the prospective customer given how it's largely unconnected to the events within the book itself.

The story within certainly contains copious amounts of violence and sex, though they feel grafted on top of a grim and elliptical psychological drama. It begins with a forlorn Fritz standing inside an empty house. She slowly wanders from room to room, examines her breasts in front of a mirror, calls her dad on the phone, only to be cruelly rejected by him. It’s a simple action sequence drawn with Gilbert’s usual black and white minimalism. But one that’s fraught with emotional weight due to his mastery of composition, time, facial expressions and body language. Every line exudes both anguish and desperation from the character. But the scene also conveys just how Fritz’s own sensuality seems to weigh heavily on her entire existence. It’s practically impossible to distinguish her history from the character she’s now supposably playing.

Fritz responds to her father’s rejection by calling on an attractive young man. But as they walk to her house, she’s accosted by a group of mysterious, visor-wearing individuals called “monitors”. “How come you look like that? How come your skin is like that? How come you talk like that?” they ask while blithely invading her personal space. After they reach her house, Fritz engages her impassive partner in vigorous love-making. But as she tries to engage him in conversation, he quietly leaves when she goes to the kitchen to prepare a meal for him.

What happens afterward is difficult to summarize and makes little sense except as some kind of fevered dream. Fritz spots the monitors outside her house and flees to the basement, only to enter a mysterious cave. when she emerges on the other side, she’s somehow acquired a new identity (complete with new hair color) as a woman named Dolores. Actually, it’s even more complicated as Fritz also plays Dolores’ brother Sonny and their estranged father, who happens to be a famous novelist. At one point Dolores becomes involved with a trio of spiritualist hucksters, Sonny has a sex change operation and impersonates Dolores. A ghost delivers a prophecy which Dolores fulfills in the most brutal manner. There are two recurring motifs: the monitors continue to hound her like a creepy Greek chorus. And the cave continues to lure characters in with promises of secret knowledge and in some cases, drive them insane. Gilbert draws it as an inky black abyss. An absolute void. Could any other metaphor be so infuriatingly on-the-nose while being so open to interpretation? Death, the Underworld, Nirvana, the Subconscious Mind, Wisdom, the Wellspring of Creativity, the Primordial Universe, the Heart of Darkness. Or maybe it’s just a game Gilbert is playing with the reader to see what they can come up with?

If so, it is an abstruse game. Gilbert is a prodigious storyteller whose powers have diminished very little. But he’s made a sharp left turn away from the humanism and diverse cast of characters found in his Palomar stories towards something a little more austere, baffling, less compassionate.

cover: Steve Martinez

design: Alexa Koenings

A meta-fictional conceit of Gilbert Hernandez’s standalone “Fritz” stories is that Rosalba “Fritz” Martinez, one of the more popular recurring characters from his Palomar series, once starred in a bunch of godawful B-movies. By adapting these movies into a growing collection of graphic novels, Gilbert can capitalize on the pre-existing appeal of this tragic, top-heavy bombshell of a figure while working on the pretense that these are new characters operating under completely different circumstances. Fritz has long been notorious for her outrageous combination of high intelligence, a voluptuous physique, light skin, voracious sexual appetite, and speaking with a “high soft lisp”, which has been alternately treated by the people around her as either endearing or deeply annoying. But she’s also been a victim of abuse at the hands of her past sexual partners, numbing the pain with bouts of heavy drinking. Love from the Shadows exploits many of those traits in Fritz’s most bravura performance and a perverse, violent, bizarre tale. I can’t really say if this is a good comic, let alone if the movie it’s pretending to be based on is worth watching. But it is strangely compelling.

And as an apparent rebuke to those fans who’ve dismissed Gilbert for his particular propensity for drawing buxom women, the graphic novel’s cover is his most confrontational yet. Painted by Steve Martinez, the pulpy, lurid quality of the bikini-clad pin-up lounging on a beach next to the ominous shadow of an unseen individual hovering behind her promises to supply all the cheap thrills expected of a clunky matinee movie, not to mention satisfy the reader’s prurient interests. It probably helps catch the eye of the prospective customer given how it's largely unconnected to the events within the book itself.

The story within certainly contains copious amounts of violence and sex, though they feel grafted on top of a grim and elliptical psychological drama. It begins with a forlorn Fritz standing inside an empty house. She slowly wanders from room to room, examines her breasts in front of a mirror, calls her dad on the phone, only to be cruelly rejected by him. It’s a simple action sequence drawn with Gilbert’s usual black and white minimalism. But one that’s fraught with emotional weight due to his mastery of composition, time, facial expressions and body language. Every line exudes both anguish and desperation from the character. But the scene also conveys just how Fritz’s own sensuality seems to weigh heavily on her entire existence. It’s practically impossible to distinguish her history from the character she’s now supposably playing.

Fritz responds to her father’s rejection by calling on an attractive young man. But as they walk to her house, she’s accosted by a group of mysterious, visor-wearing individuals called “monitors”. “How come you look like that? How come your skin is like that? How come you talk like that?” they ask while blithely invading her personal space. After they reach her house, Fritz engages her impassive partner in vigorous love-making. But as she tries to engage him in conversation, he quietly leaves when she goes to the kitchen to prepare a meal for him.

What happens afterward is difficult to summarize and makes little sense except as some kind of fevered dream. Fritz spots the monitors outside her house and flees to the basement, only to enter a mysterious cave. when she emerges on the other side, she’s somehow acquired a new identity (complete with new hair color) as a woman named Dolores. Actually, it’s even more complicated as Fritz also plays Dolores’ brother Sonny and their estranged father, who happens to be a famous novelist. At one point Dolores becomes involved with a trio of spiritualist hucksters, Sonny has a sex change operation and impersonates Dolores. A ghost delivers a prophecy which Dolores fulfills in the most brutal manner. There are two recurring motifs: the monitors continue to hound her like a creepy Greek chorus. And the cave continues to lure characters in with promises of secret knowledge and in some cases, drive them insane. Gilbert draws it as an inky black abyss. An absolute void. Could any other metaphor be so infuriatingly on-the-nose while being so open to interpretation? Death, the Underworld, Nirvana, the Subconscious Mind, Wisdom, the Wellspring of Creativity, the Primordial Universe, the Heart of Darkness. Or maybe it’s just a game Gilbert is playing with the reader to see what they can come up with?

If so, it is an abstruse game. Gilbert is a prodigious storyteller whose powers have diminished very little. But he’s made a sharp left turn away from the humanism and diverse cast of characters found in his Palomar stories towards something a little more austere, baffling, less compassionate.

11/13/2015

11/11/2015

11/09/2015

11/07/2015

The Ticking

by Renée French

As with any comic created by Renée French, The Ticking’s strength is found in her inimitable visuals. French draws these flat, super-deformed cartoon characters, but renders them not with solid black lines but with soft graphite. The resulting three-dimensional quality of the art makes their presence on the page ambiguously disturbing, like a barely remembered vision or nightmare. There’s just a slight hint of the “uncanny valley”, which actually helps enhance the strangeness. But this isn’t done in the service of satire or social commentary. French’s gaze is trained inward, and her sympathies clearly lie with the ugly and the disfigured.

The preciousness of the art is further enhanced by the stark presentation. Most pages contain one or two square panels, stacked vertically. Any dialogue is displayed in handwritten script below each panel. This organic minimalism is exquisite, but very effective, and makes for a quick read. It lends the simple story within a modern fairy tale quality.

The book starts shockingly enough with the birth of its hero Edison Steelhead, a baby possessing a grotesquely large head with beady eyes so far apart they’re located at the side rather than the front of his face. His mother dies on the kitchen floor from the act of giving birth, and his grieving father Calvin raises Edison in isolation on a remote island lighthouse. While this may seem like Calvin is protecting from the outside world, the reader is clued in early that it’s as much an expression of self-loathing as it is of loving concern. Calvin blames himself for his son’s physical imperfections.

Raised in such a nurturing but stifling environment, Edison learns to cope by observing everything and drawing in his sketchbook. He catalogs the smallest details of his world with diagrammatic line drawings, which French reproduces as one page spreads. They serve as important story beats, pausing the narrative and letting the reader into Edison’s developing mind. As his imagination and curiosity grow, Edison slowly comes to chafe under his father’s tight control. When Calvin unexpectedly brings home a little sister named Patrice, a chimpanzee wearing a dress, Edison begins to realize the need to explore the wider world on his own terms.

That is the heart of The Ticking - the dynamic between parent and child. How parents tend to see themselves in their children, how children have to struggle to establish their own identity, and how this relationship is ultimately inescapable. It’s a very old story, but one told in French’s offbeat style: full of understated emotions, long silences, and warm but surreal imagery loaded with symbolism, both obvious and not so obvious.

As with any comic created by Renée French, The Ticking’s strength is found in her inimitable visuals. French draws these flat, super-deformed cartoon characters, but renders them not with solid black lines but with soft graphite. The resulting three-dimensional quality of the art makes their presence on the page ambiguously disturbing, like a barely remembered vision or nightmare. There’s just a slight hint of the “uncanny valley”, which actually helps enhance the strangeness. But this isn’t done in the service of satire or social commentary. French’s gaze is trained inward, and her sympathies clearly lie with the ugly and the disfigured.

The preciousness of the art is further enhanced by the stark presentation. Most pages contain one or two square panels, stacked vertically. Any dialogue is displayed in handwritten script below each panel. This organic minimalism is exquisite, but very effective, and makes for a quick read. It lends the simple story within a modern fairy tale quality.

The book starts shockingly enough with the birth of its hero Edison Steelhead, a baby possessing a grotesquely large head with beady eyes so far apart they’re located at the side rather than the front of his face. His mother dies on the kitchen floor from the act of giving birth, and his grieving father Calvin raises Edison in isolation on a remote island lighthouse. While this may seem like Calvin is protecting from the outside world, the reader is clued in early that it’s as much an expression of self-loathing as it is of loving concern. Calvin blames himself for his son’s physical imperfections.

Raised in such a nurturing but stifling environment, Edison learns to cope by observing everything and drawing in his sketchbook. He catalogs the smallest details of his world with diagrammatic line drawings, which French reproduces as one page spreads. They serve as important story beats, pausing the narrative and letting the reader into Edison’s developing mind. As his imagination and curiosity grow, Edison slowly comes to chafe under his father’s tight control. When Calvin unexpectedly brings home a little sister named Patrice, a chimpanzee wearing a dress, Edison begins to realize the need to explore the wider world on his own terms.

That is the heart of The Ticking - the dynamic between parent and child. How parents tend to see themselves in their children, how children have to struggle to establish their own identity, and how this relationship is ultimately inescapable. It’s a very old story, but one told in French’s offbeat style: full of understated emotions, long silences, and warm but surreal imagery loaded with symbolism, both obvious and not so obvious.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)