Go to: Light vs. Line (via Tom Spurgeon)

1/29/2011

1/28/2011

1/27/2011

Shonen Transform

Go to: Montrose Sketchbook by Kittyhawk (Warning: NSFW)

1/26/2011

Sulyap (Part 1)

The comic anthology Sulyap is fairly representative of Komikon itself - a hodgepodge of ideas, foreign influences, genres, visual styles, and varying levels of quality and artistic ambition. There's no common aesthetic approach that unites the stories within. The only thing the contributors have in common (other than obvious things like nationality) is that they all self-publish, mostly in black and white, and they're all pretty young. A certain naive enthusiasm permeates the collection, not entirely dissimilar to those found within most of the stories of the Flight anthology series. And like Flight, there's also a clear preference for fantasy as a vehicle for expression. For these reasons, Sulyap may not appeal to everyone. There's a great deal of sincere energy within that can sometimes preclude more sage introspection.

Ambition by Ian Olympia

Ian Olympia is one of those manga-inspired creators who's thoroughly mastered all the details of his idols' drawing style, despite the odds. His lithe, exaggerated, figures are beautifully rendered. He gets the typical manga hyper-expressiveness just right. He's also one of those artists who, more often than not, skimps on the backgrounds to concentrate on the characters. I guess that's why speed lines were invented. Olympia keeps the narrative off-kilter by constantly shifting the perspective so that everything is seen either from above or from below. Even during quiet moments, the tension never abates. His extreme black and white line art generates a stark and unforgiving world. Depending on the reader's own tastes, the storytelling is either very cool or slightly nauseating.

The story itself is an adolescent melodrama of idealistic love vs. worldly ambition with an ironic twist ending. To any young 'un who can't suss out the message: you're supposed to pick love over ambition, especially if that ambition means joining the rank and file of some criminal organization. It becomes doubly ironic when the would-be lovers are forced to kill each other (Oh my! The tragedy). Or did the moral just get slightly muddled during transmission? Maybe kids should just be more careful with who they date? I'm not up with my crime manga, but this seems like a hoary concept told ably enough.

Baboy by Mel Khristopher Casipit

Mel Casipit is something of a darling at Komikon, given the number of times he's been recognized by the con's organizers. Baboy was his first prize-winning mini-comic, and is reprinted here with its 2010 sequel. Casipit's original style is rough, full of heavy cross-hatching and inky black spaces. His figures betray a shonen manga influence, mashed with an expressionist line and indie production values. Most of his panels are large and irregular, so as to better mirror the emotional turmoil found within its contents. There's some danger of the visuals becoming confusing at times. But for the most part, it holds together. There's certainly a laudable willingness to experiment with the form, not to mention a great deal of emotional vigor.

In this mostly silent tale, a nameless young man roams a surreal landscape. He's either bent on ending his life, or at least has simply lost the will to live. Everywhere he goes, he's hounded by people who clearly fear and loathe him. But he's not Frankenstein's monster, or a Marvel Comics character. He just transforms into a giant, ferocious, blood thirsty, were-boar. He kills anyone who crosses him, but his tormentors are as much at fault, for he only becomes the "baboy" when in danger. So he's trapped in a circle of never-ending violence without any possibility of escape or redemption.

It's not clear to me why Casipit felt the need for a sequel, but there obviously has been a considerable degree of artistic evolution within that intervening two year period. His visuals are more polished. His figures are rounder and cuter. He's also reigned-in the irregularly shaped panels and black areas. The effect is noticeably brighter in look and tone. Whereas the first story is basically a dark mood piece, the second has a more conventional plot about the protagonist defending a hapless family from nefarious elements. There's even a possible romantic angle thrown in for good measure. Not that this resolves the protagonist's primary source of misery, but it leaves open the possibility for future Baboy stories.

Goodbye Rubbit by RH Quilantang

At first glance, Goodbye Rubbit looks like a children's story about leaving the nest. All the characters look like a cross between Teletubbies and Nintendo Game Boys. But it's more about young love and romantic break-ups. RH Quilantang presents a sweet and relatively un-neurotic tale of heartache and the need to move on, using easily accessible and broad metaphors set in an imaginary cartoon world. This is without a doubt the cutest story in the entire collection.

Kalayaan by Gio Paredes

Gio Paredes has been publishing his superhero comic series Kalayaan for more than three years now. I've written about my dislike for the more excessive habits of the Image house style in the past. Kalayaan's look owes a lot to Rob Liefeld and his ilk. But that's not my main problem with the comic. Paredes just doesn't go beyond clumsy mimicry, at least not at this point - a reprint of his inaugural issue. The figures are very stiff and inexpressive (even by the style's standards), and the perspective and rendering of the backgrounds are quite crude. This story exemplifies what happens when artists just copy from other artists, without carefully observing nature - there's a tendency for the style to degenerate after several iterations.

Kalayaan (which means "freedom") is a kind of Filipinized hybrid of Captain America and Superman - he wears patriotic colors and symbols (he even carries a shield) and operates with the standard superpower combo of inhuman strength, flight, and a super-tough hide. Like a typical first issue from the early nineteen nineties, the story jumps right into the middle of the action. The hero's background remains largely unexplained. The centerpiece is a brutal slugfest between Kalayaan and some Sabretooth clone. And it leaves the reader hanging with the sudden entrance of several ominous figures. Wait, this was made in 2007? I'm not sure if Kalayaan is so bad it's good. The most that I can say about it is that there is ostensibly a lot of devotion, and strong belief in its own tropes, empowering the project. All in all, Kalayaan is, in terms of technique, the least impressive contribution to the Sulyap anthology.

Part 2 will deal with the second half of Sulyap.

Ambition by Ian Olympia

Ian Olympia is one of those manga-inspired creators who's thoroughly mastered all the details of his idols' drawing style, despite the odds. His lithe, exaggerated, figures are beautifully rendered. He gets the typical manga hyper-expressiveness just right. He's also one of those artists who, more often than not, skimps on the backgrounds to concentrate on the characters. I guess that's why speed lines were invented. Olympia keeps the narrative off-kilter by constantly shifting the perspective so that everything is seen either from above or from below. Even during quiet moments, the tension never abates. His extreme black and white line art generates a stark and unforgiving world. Depending on the reader's own tastes, the storytelling is either very cool or slightly nauseating.

The story itself is an adolescent melodrama of idealistic love vs. worldly ambition with an ironic twist ending. To any young 'un who can't suss out the message: you're supposed to pick love over ambition, especially if that ambition means joining the rank and file of some criminal organization. It becomes doubly ironic when the would-be lovers are forced to kill each other (Oh my! The tragedy). Or did the moral just get slightly muddled during transmission? Maybe kids should just be more careful with who they date? I'm not up with my crime manga, but this seems like a hoary concept told ably enough.

Baboy by Mel Khristopher Casipit

Mel Casipit is something of a darling at Komikon, given the number of times he's been recognized by the con's organizers. Baboy was his first prize-winning mini-comic, and is reprinted here with its 2010 sequel. Casipit's original style is rough, full of heavy cross-hatching and inky black spaces. His figures betray a shonen manga influence, mashed with an expressionist line and indie production values. Most of his panels are large and irregular, so as to better mirror the emotional turmoil found within its contents. There's some danger of the visuals becoming confusing at times. But for the most part, it holds together. There's certainly a laudable willingness to experiment with the form, not to mention a great deal of emotional vigor.

In this mostly silent tale, a nameless young man roams a surreal landscape. He's either bent on ending his life, or at least has simply lost the will to live. Everywhere he goes, he's hounded by people who clearly fear and loathe him. But he's not Frankenstein's monster, or a Marvel Comics character. He just transforms into a giant, ferocious, blood thirsty, were-boar. He kills anyone who crosses him, but his tormentors are as much at fault, for he only becomes the "baboy" when in danger. So he's trapped in a circle of never-ending violence without any possibility of escape or redemption.

It's not clear to me why Casipit felt the need for a sequel, but there obviously has been a considerable degree of artistic evolution within that intervening two year period. His visuals are more polished. His figures are rounder and cuter. He's also reigned-in the irregularly shaped panels and black areas. The effect is noticeably brighter in look and tone. Whereas the first story is basically a dark mood piece, the second has a more conventional plot about the protagonist defending a hapless family from nefarious elements. There's even a possible romantic angle thrown in for good measure. Not that this resolves the protagonist's primary source of misery, but it leaves open the possibility for future Baboy stories.

Goodbye Rubbit by RH Quilantang

At first glance, Goodbye Rubbit looks like a children's story about leaving the nest. All the characters look like a cross between Teletubbies and Nintendo Game Boys. But it's more about young love and romantic break-ups. RH Quilantang presents a sweet and relatively un-neurotic tale of heartache and the need to move on, using easily accessible and broad metaphors set in an imaginary cartoon world. This is without a doubt the cutest story in the entire collection.

Kalayaan by Gio Paredes

Gio Paredes has been publishing his superhero comic series Kalayaan for more than three years now. I've written about my dislike for the more excessive habits of the Image house style in the past. Kalayaan's look owes a lot to Rob Liefeld and his ilk. But that's not my main problem with the comic. Paredes just doesn't go beyond clumsy mimicry, at least not at this point - a reprint of his inaugural issue. The figures are very stiff and inexpressive (even by the style's standards), and the perspective and rendering of the backgrounds are quite crude. This story exemplifies what happens when artists just copy from other artists, without carefully observing nature - there's a tendency for the style to degenerate after several iterations.

Kalayaan (which means "freedom") is a kind of Filipinized hybrid of Captain America and Superman - he wears patriotic colors and symbols (he even carries a shield) and operates with the standard superpower combo of inhuman strength, flight, and a super-tough hide. Like a typical first issue from the early nineteen nineties, the story jumps right into the middle of the action. The hero's background remains largely unexplained. The centerpiece is a brutal slugfest between Kalayaan and some Sabretooth clone. And it leaves the reader hanging with the sudden entrance of several ominous figures. Wait, this was made in 2007? I'm not sure if Kalayaan is so bad it's good. The most that I can say about it is that there is ostensibly a lot of devotion, and strong belief in its own tropes, empowering the project. All in all, Kalayaan is, in terms of technique, the least impressive contribution to the Sulyap anthology.

Part 2 will deal with the second half of Sulyap.

1/24/2011

Illustration: Kaiju Anatomy

Go to: Illustrated anatomy of Gamera and foes, from Kaijū-Kaijin Daizenshū movie monster book series, by Pink Tentacle (via Cyriaque Lamar)

I loved this kind of trivia as a kid. Where did Gamera's fire breath come from?

1/22/2011

More NonSense: The Geek shall Inherit the Earth?

|

| Harvey and Toby on "Revenge of the Nerds" from American Splendor, by Harvey Pekar and Bill Knapp |

Noah Berlatsky's social critique of The Big Bang Theory instantly reminded me of the late Harvey Pekar's takedown of Revenge of the Nerds (not the film adaptation, but the original comic story). But at least he ends his piece with a backhanded compliment that recognizes its particular brand of humor.

Sean T. Collins posts the first truly critical commentary on Dirk Deppey's long running Journalista. I don't disagree with a lot of what he wrote, especially with his own distaste for Dirk's later style of industry analysis, which could be grating at times for being relentlessly contrarian just for its own sake. But as much as I like Tom Spurgeon as a news source, I'm still a big fan of Dirk's digest-format approach to link-blogging. The TCJ site looks all the more poorer without his daily postings. What does TCJ do these days?

Roland Kelts reports on the fallout over the passing of Bill 156 in Japan. So much for practicing wa. The otaku are rebelling.

Patton Oswalt mourns the death of classic geek culture as he sees it. Weren't we supposed to outgrow those things anyway? Oh yeah, we didn't.

Christopher Butcher and Kevin Melrose comment on the nominations for this year's GLAAD Media Awards, one of the more superhero-friendly (read biased) comic awards.

1/20/2011

Bad Television: The Colony Season 2

Season two of Discovery Channel's popular reality TV show The Colony recently concluded on local cable. As with many reality TV programs, the ending left me slightly disappointed with the outcome. Most shows fail to provide the hoped for cathartic moment, and The Colony in particular stretches credulity more than most. Like past serials such as 1900 House or Frontier House, the participants are asked to live within a simulated environment. Unlike them, the simulation itself is more fanciful than believable. The main problem is the manufactured storyline being superimposed on top of the basic premise.

In the series, the "colonists" attempt to survive within a cordoned-off area designed to recreate a post-apocalyptic urban environment. In both seasons, they scavenge for food and water while working on increasingly elaborate builds to shore up power and improve security. But because their immediate area is too small to begin with and resources within it too scarce, they're inevitably forced to "exit" the colony, at which point the series ends. This scenario sounds counterintuitive. Why are the colonists more concerned with producing electricity for power tools over procuring food and clean water? If civilization really collapsed, shouldn't the survivors take to the road sooner rather than become trapped in an inhospitable city? But since that's a tall order to simulate, what happens is the polar opposite: the colonists are gradually reduced to skin and bones while working overtime on generators and what not, unable to leave until the very last episode. That no one from either season attempts to do something that would be long-term sustainable, such as farming or raising livestock, spells out the futility of this "experiment".

Another way in which the format trumps realism is the colonists themselves. Like most reality TV contestants, they're a motley crew of total strangers forced to cohabit with one another. This results in the usual reality TV hijinks. Viewers have complained that the casting in season one was biased towards the more technologically proficient. But the show also ignored something the historically-based shows got right - that settlements tend to be established by people who already know each other. Otherwise it's just another penal colony.

As if the reasons for not being able to leave sooner weren't silly enough, the colonists have to contend with Hollywood-style complications. In both seasons, the colonists were harassed by paid actors playing the role of "marauders". Rather inexplicably, the marauders possessed greater numbers, were better fed, and better armed. They're villains right out of Lost or Mad Max. Yet they can never completely overwhelm the colonists since that would prematurely end the show. The colonists aren't allowed to join up with the marauders. So they're constantly subject to annoying raids. After all, the cast is never meant to be put in real danger. In both seasons, the series makes it look as if the colonists were eventually driven out by the marauders rather than admitting to the more mundane meta explanation that the allotted time for filming (not to mention the local supply of food and raw materials) had simply run out. So the presence of the marauders only betrays the contrived nature of the whole show. I don't remember the participants of Frontier House having to pretend they were under assault from armed bandits.

Despite these quibbles, season one was actually decent nerd entertainment, if only because the colonists were able to come up with so many nifty contraptions. The producers did stack the deck by not only casting engineers and mechanics, but by also situating them within a spacious warehouse. The producers rightfully fixated on the builds, given that this is the kind of infotainment the Discovery Channel excels at. Season two's colonists are younger and prettier, but not as personally compelling, well-equipped, or well-protected from outside interference. It's as if the producers responded to criticisms of season one by going out of their way to torture season two's cast. During the raids, at least two colonists are pepper sprayed, and one is even kidnapped for ransom. They're incompetent at procuring food. In fact, they're so piss-poor at hunting, gathering, and defending themselves that another colonist is introduced later in series, and his survival training pretty much saves them from dying from malnutrition (or at least that's what's being implied). If the show was really concerned about demonstrating proper survival techniques, it should have have included him from the beginning.

The producers seem to have also listened to criticisms about the ambiguous nature of season one's catastrophe. In season two it's defined as a global viral pandemic. Unfortunately the extra details have a way of making the season's story arc even more convoluted. For example, the starting premise is that the colonists were carefully quarantined by the Viral Outbreak Protection Agency (VOPA) to ensure their health, only to be dumped onto an insecure location where they're vulnerable to attacks from marauders and the infected alike. VOPA's other baffling actions are just another excuse to mess with the cast's emotional well-being. At one point they deliberately botch a food drop, yet safely deliver pre-recorded messages from the colonist's real-word families. But the colonists themselves engage in their fair share of illogical behavior in order to stick to the storyline. When some of them are scouting an area for a potential new settlement, they are attacked by one of the infected. Rather than counting it out as too dangerous to inhabit, the group decides it's an ideal location. On the final day of filming, the colonists stage a pointless counter-raid on the marauders, probably done just so the series could have a climactic action scene. Are the producers trying to make them look stupid?

The second season of The Colony isn't all bad. The builds still display considerable resourcefulness and practical knowledge. But the insistence that this is a serious post-apocalyptic experiment is starting to wear thin. And it doesn't help that this season's cast behaved like a bunch of second bananas in search for a lead actor to fall behind. Their tribulations are no longer enjoyable to watch the second time around. If The Colony returns for a third season, bring back the nerds.

1/19/2011

1/17/2011

Who is Jake Ellis? #1

By Nathan Edminson and Tonci Zonjic

The most attractive thing about Who is Jake Ellis? is the command of storytelling on display. The title poses a question, and is aided by a front cover design portraying two figures looking like poster boys from some Hollywood noir. They probably could be played by two A-list actors. The streamlined art by Tonci Zonjic ably conveys their contrasting personalities: the one colored in red is ruggedly handsome and clearly a man of action, while the brooding figure dressed in black is shaded in grays and draped in shadows. The reader is immediately thrown into the action in a very clever opening. The handsome figure, whose name is Jon Moore, is staging the kind of daring escape from unscrupulous characters worthy of any action movie hero. But curiously enough, he seems to be talking to himself rather than paying attention to what's going on around him. This scene is then repeated, almost verbatim. But this time the shadowy figure is hovering over Jon and relaying instructions, which he responds to and unquestioningly follows. Jon's nonsensical words suddenly make a lot more sense. No one can see or hear him except Jon, and he's the mysterious Jake Ellis the title is referring to.

This introduction is an effective way to hook the reader, and it summarizes Jake and Jon's relationship. For unknown reasons, Jake is protective of Jon, while Jon is dependent on Jake as a defensive measure. Jake is not a simple hallucination because he can see things that aren't in Jon's direct line of sight. He also seems to posses limited precognitive abilities since he can sense impending danger. They don't interact like friends, but their dialogue suggests that they've had enough time to grow accustomed to one another, as Jon doesn't seem to mind Jake's constant presence, regardless of the circumstances. Jake is probably immaterial, since he seems unaffected by the external environment, and is able to keep up with Jon without exhibiting any significant physical exertion.

That last part is pertinent because Jon is constantly on the run. After the opening, which takes place in Spain, Jon has made his way to France. It isn't long before he's involved in another cat and mouse chase. One moment he's seducing a waitress, and the next he's jumping off roofs, dashing into Strasbourg Cathedral, and smashing through boutique store windows. At first he thinks it's the same people from Spain. But it soon becomes apparent from the dialogue between the two that Jon has more than one dangerous foe to contend with.

While Jake is the most interesting enigma, writer Nathan Edminson provides little background about Jon himself. The propulsive action, quick shifts between exotic European locations, combined with the careful parcelling of information, produce an inviting enough riddle to hold the reader's attention. Edminson and Zonjic certainly make for a very compelling creative team who seem to be in synch with one another. It'll be interesting to see whether the payoff at the end will live up to the promise of its setup.

The most attractive thing about Who is Jake Ellis? is the command of storytelling on display. The title poses a question, and is aided by a front cover design portraying two figures looking like poster boys from some Hollywood noir. They probably could be played by two A-list actors. The streamlined art by Tonci Zonjic ably conveys their contrasting personalities: the one colored in red is ruggedly handsome and clearly a man of action, while the brooding figure dressed in black is shaded in grays and draped in shadows. The reader is immediately thrown into the action in a very clever opening. The handsome figure, whose name is Jon Moore, is staging the kind of daring escape from unscrupulous characters worthy of any action movie hero. But curiously enough, he seems to be talking to himself rather than paying attention to what's going on around him. This scene is then repeated, almost verbatim. But this time the shadowy figure is hovering over Jon and relaying instructions, which he responds to and unquestioningly follows. Jon's nonsensical words suddenly make a lot more sense. No one can see or hear him except Jon, and he's the mysterious Jake Ellis the title is referring to.

This introduction is an effective way to hook the reader, and it summarizes Jake and Jon's relationship. For unknown reasons, Jake is protective of Jon, while Jon is dependent on Jake as a defensive measure. Jake is not a simple hallucination because he can see things that aren't in Jon's direct line of sight. He also seems to posses limited precognitive abilities since he can sense impending danger. They don't interact like friends, but their dialogue suggests that they've had enough time to grow accustomed to one another, as Jon doesn't seem to mind Jake's constant presence, regardless of the circumstances. Jake is probably immaterial, since he seems unaffected by the external environment, and is able to keep up with Jon without exhibiting any significant physical exertion.

That last part is pertinent because Jon is constantly on the run. After the opening, which takes place in Spain, Jon has made his way to France. It isn't long before he's involved in another cat and mouse chase. One moment he's seducing a waitress, and the next he's jumping off roofs, dashing into Strasbourg Cathedral, and smashing through boutique store windows. At first he thinks it's the same people from Spain. But it soon becomes apparent from the dialogue between the two that Jon has more than one dangerous foe to contend with.

While Jake is the most interesting enigma, writer Nathan Edminson provides little background about Jon himself. The propulsive action, quick shifts between exotic European locations, combined with the careful parcelling of information, produce an inviting enough riddle to hold the reader's attention. Edminson and Zonjic certainly make for a very compelling creative team who seem to be in synch with one another. It'll be interesting to see whether the payoff at the end will live up to the promise of its setup.

1/15/2011

1/14/2011

Martial Myths: Sanshiro Sugata

Sanshiro Sugata is an often overlooked fight film. Yet it is the prototypical cinematic example of the tale of callow youth maturing via the study of the art of combat. The formula's been used in movies from Star Wars to The Karate Kid, to No Retreat No Surrender, and countless fight manga like Naruto or Bleach. Released in 1943, it marks the directorial debut of Akira Kurosawa. But for the purposes of this post, it's important because it's loosely based on the history of Kodokan Judo - simply known to most as "judo", which was established in 1882 by Japanese educator Jigorō Kanō. More specifically, the main protagonist is generally recognized to be based on Shiro Saigo, one of Kanō's star pupils.

The original story was a novel written by the son of another of Kanō's senior students. But the actual Saigo was a shadowy figure, making him an ideal candidate for hagiography. What's known about him is that he joined the Kodokan soon after its founding, and was a participant in a series of matches that took place in 1886. This event, which was hosted by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police department, pitted the Kodokan against fighters from other jujutsu organizations. There's not much hard information to go by, and most of it comes from judo sources. It's not even clear what rules were being enforced during the event. What's reported is that Saigo won his match with a throw so forceful it knocked his opponent unconscious (the film has a more tragic outcome). The Kodokan ended up winning almost all of the matches, and has since then exploited the victory for bragging rights over its jujutsu rivals. More recently, contentious claims have been made (containing no real proof) that Saigo was already a high level jujutsu exponent when he joined the Kodokan. Whatever the case, Saigo left the Kodokan in 1890 (or was booted out, depending on who you ask), became a professional journalist, and died in 1922.

Unsurprisingly, Sanshiro Sugata reflects a pro-judo bias. Not only is judo implied to be technically and philosophically superior to jujutsu, but more morally outstanding as well. A story needs a bad guy after all. So we have minor figures like the thugs who harass Shogoro Yano (the fictionalized Kanō), to the brooding Gennosuke Higaki, who battles Sugata in the film's final showdown. On the other hand, the scholarly Yano lectures the wayward Sugata on the need to transcend displays of mere physical force, and to learn the value of compassion, in order to become a true judoka.

However there's much more to the film than a vehicle for stoking style vs. style arguments. Despite the subject matter, Kurosawa doesn't seem particularly interested in examining the factional rivalry between judo and jujutsu as he is in charting the personal growth of Sugata. Considering that this was a wartime studio product, what's remarkable is how very little propaganda it contains. On the contrary, it betrays a certain subversive viewpoint. While the jujutsu practitioners are the film's antagonists, they're not cardboard villains that need to be crushed. And in complete contrast to the vast majority of genre fight films, Sanshiro Sugata goes out of its way to rob the physical confrontations of easy triumphalism. To any fan of Kurosawa's later masterpieces, this shouldn't come as any surprise. Any glory or honor to be gained in defeating a dangerous foe has largely disappeared by the time Sugata concludes his duel with Higaki.

The fight scenes are fairly simple, which compliments Kurosawa's introspective approach. They're comparitively realistic, but not necesarilly accurate since all of them look like judo randori - the fighters mostly limit themselves to grabbing their opponent's lapel and attempting a throw, with an occasional submission made. Whether these were the rules for the police-hosted matches is arguable. But why the heck wouldn't someone try to finish a fight by throwing a punch during an unregulated street brawl?

Sanshiro Sugata must have been a letdown to the wartime government. What they probably wanted was a series of glorious fight scenes that could be used to inflame the martial spirit of Japan's youth, and hopefully they'd want to become kamikaze pilots. What they got instead was something that could have been read as being critical of its military policies. Kurosawa would go on to direct a more conventional sequel which had the hero go up against those damn foreigners. Naturally, the critics hated it. But that's what martial arts films are for. Sanshiro smash puny Americans!

1/13/2011

1/07/2011

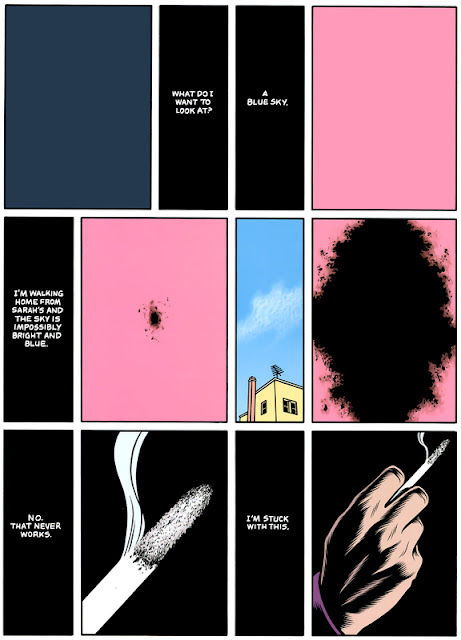

X'ed Out

X'ed Out was perhaps the most unsettling comic book to come out in 2010 that I've read. The first major work of Charles Burns since his critically lauded Black Hole in 2004, the two share common themes and ticks: an exploration of the sense of alienation and disconnect felt by adolescents, a fascination with body horror, and a stream of conscious style of writing used to convey the inner turmoil of his protagonists. This last characteristic is enlarged upon in X'ed Out as the book continuously shifts back and forth between several settings in a nonlinear, seemingly random, order. All of them focus on the experiences of a young man named Doug. The book presents the reader a neurological jumble of memories, thoughts, and feelings. Doug himself is as much bewildered by them as the reader is when attempting to tie together the threads of his tattered life.

Because the story is seen from Doug's own point of view, it's an extremely claustrophobic experience. Doug is a person trapped inside his own head, and the reader is offered no relief in the form of another character's perspective. There's a younger teenage Doug, and a somewhat older bedridden Doug who regularly takes unspecified pills, and becomes easily upset over the smallest disturbance. It's not clear how the two characters are connected. Between them, there's another Doug who inhabits a bizarre nightmare world were he looks like a poor man's version of Hergé's famous boy hero Tintin. Is this a dream, an idle fantasy, or an alternate reality? Like his bedridden self, this Doug wears a purple bathrobe and has one side of his head shaved and bandaged for unexplained reasons. It's a freakish puzzle that will leave the reader either very frustrated or highly stimulated. Or a maybe a little of both.

The page layouts follow a traditional grid pattern to lend the story some visual certainty. But otherwise, X'ed Out uses a more unconventional, polyphonic, labyrinth, narrative structure. Burns doesn't bother with establishing shots to demarcate his scenes. Rather, each flows unexpectedly into one another. The book is rich in motifs, both visual and verbal, to help clue the reader in: Snatches of repeated phrases, photographs, repetitious views, symbolic imagery, and fields of pure color. The presence of color makes it a very different work from Black Hole. It wields it as a tool to transition between scenes and as a way to add a further layer of meaning. The color palette hews to the Tintin books preference for flat, bright, pastel quality, local colors. And while Hergé and Burns have contrasting drawing styles, the coloring works equally well, but for different reasons. Within the nightmare world, Doug is like Tintin the globe-trotting explorer of exotic locals. But whereas Hergé's ligne claire exhibits a similarly bright world of clear-cut moral distinctions, in Burn's case the color serves to highlight the grotesque imagery delineated by Burns bolder strokes and murky black areas. It's a beautifully clever subversion of Hergé's world view. What emerges is more primal and terrifying.

X'ed Out doesn't cast the reader entirely adrift. Doug's most vivid memories center around an enigmatic love interest named Sarah. Burns also provides an anchor for the story in the flashbacks to Doug's younger self: they reveal that he was a involved in the punk rock scene as a performer of spoken word pieces, he called himself Nitnit (An inversion of Tintin), and he wore a Tintin mask during his performances. They paint a more complete portrait of Doug's and Sarah's personalities, and are the most straightforward parts in the book. Because of the information they supply, a number of disturbing possibilities begin to emerge on how the various timelines will converge in the end. In particular, the front and back cover illustrations, a shout out to The Shooting Star, become downright creepy in it's implications after reading the last page.

This book is only the opening chapter of a larger work. Like Black Hole, Burns has chosen to serialize his story before releasing a collected edition. But whereas the earlier work was first published in pamphlet form, X'ed Out utilizes the larger album format. It's a good choice, as it feels more substantial and exhibits more of Burns talents to entice the reader into the story (not to mention that this is also another way to relate it to Tintin). With this in mind, X'ed Out will require several re-readings, especially after the final installment is published.

Because the story is seen from Doug's own point of view, it's an extremely claustrophobic experience. Doug is a person trapped inside his own head, and the reader is offered no relief in the form of another character's perspective. There's a younger teenage Doug, and a somewhat older bedridden Doug who regularly takes unspecified pills, and becomes easily upset over the smallest disturbance. It's not clear how the two characters are connected. Between them, there's another Doug who inhabits a bizarre nightmare world were he looks like a poor man's version of Hergé's famous boy hero Tintin. Is this a dream, an idle fantasy, or an alternate reality? Like his bedridden self, this Doug wears a purple bathrobe and has one side of his head shaved and bandaged for unexplained reasons. It's a freakish puzzle that will leave the reader either very frustrated or highly stimulated. Or a maybe a little of both.

The page layouts follow a traditional grid pattern to lend the story some visual certainty. But otherwise, X'ed Out uses a more unconventional, polyphonic, labyrinth, narrative structure. Burns doesn't bother with establishing shots to demarcate his scenes. Rather, each flows unexpectedly into one another. The book is rich in motifs, both visual and verbal, to help clue the reader in: Snatches of repeated phrases, photographs, repetitious views, symbolic imagery, and fields of pure color. The presence of color makes it a very different work from Black Hole. It wields it as a tool to transition between scenes and as a way to add a further layer of meaning. The color palette hews to the Tintin books preference for flat, bright, pastel quality, local colors. And while Hergé and Burns have contrasting drawing styles, the coloring works equally well, but for different reasons. Within the nightmare world, Doug is like Tintin the globe-trotting explorer of exotic locals. But whereas Hergé's ligne claire exhibits a similarly bright world of clear-cut moral distinctions, in Burn's case the color serves to highlight the grotesque imagery delineated by Burns bolder strokes and murky black areas. It's a beautifully clever subversion of Hergé's world view. What emerges is more primal and terrifying.

X'ed Out doesn't cast the reader entirely adrift. Doug's most vivid memories center around an enigmatic love interest named Sarah. Burns also provides an anchor for the story in the flashbacks to Doug's younger self: they reveal that he was a involved in the punk rock scene as a performer of spoken word pieces, he called himself Nitnit (An inversion of Tintin), and he wore a Tintin mask during his performances. They paint a more complete portrait of Doug's and Sarah's personalities, and are the most straightforward parts in the book. Because of the information they supply, a number of disturbing possibilities begin to emerge on how the various timelines will converge in the end. In particular, the front and back cover illustrations, a shout out to The Shooting Star, become downright creepy in it's implications after reading the last page.

This book is only the opening chapter of a larger work. Like Black Hole, Burns has chosen to serialize his story before releasing a collected edition. But whereas the earlier work was first published in pamphlet form, X'ed Out utilizes the larger album format. It's a good choice, as it feels more substantial and exhibits more of Burns talents to entice the reader into the story (not to mention that this is also another way to relate it to Tintin). With this in mind, X'ed Out will require several re-readings, especially after the final installment is published.

1/04/2011

Bill on Big Numbers

Go to: Big Numbers #3 by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz. Sienkiewicz speaks out about Big Numbers, courtesy of Pádraig Ó Méalóid and Sean T. Collins

Kinetic Energy

Go to: All Star Comics #59 panel by Gerry Conway and Wally Wood, courtesy of Alex Boney

1/03/2011

1/01/2011

More NonSense: Looking Back, Looking Forward

|

| Diesel Sweeties by Richard Stevens |

I can't say that this was a good year for me. But I certainly did blog a lot more than I did last year. Or the year before that. That's almost three years of steadily increasing productivity since I began this little experiment in self-expression - A very faint victory. So now what? Things are still as precarious as ever, so no promises will be made. Frankly, I'm terrified for the future.

The Year that was 2010

Brigid Alverson link-blogging

Kevin Melrose link-blogging

Joe Gross: The best comics and graphic novels of 2010

Scott Cederlund: Least objectionable comics of 2010

Bob Temuka: A top ten comics for 2010 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1

Katherine Dacey: The best manga of 2010

Dave Ferraro: 10 Best Superhero Comics of 2010

Dave Ferraro: 10 Best Manga of 2010

Derik Badman: Best Print Comics of 2010

Derik Badman: Best Webcomics of 2010

Kevin Church: Not A Best Of: Comics In 2010

Matt Seneca: My 10 from 2010

Dave Carter: Amazon Top 50

Andrew Wheeler: My Favorite Books of the Year: 2010

Tom Tomorrow: 2010 The year in crazy, Pt 1, 2

Tatsuya Ishida: Live a Little

Paolo Chikiamko komiks reviews link-blogging

Stephen Saperstein Frug: A Final Quote for 2010

Roland Kelts: Looking back to move forwards: A few good gift books

Tom Spurgeon: Some Of The Great Comics People Lost To Us In 2010

Brad Rice: Japanator's top 10 anime series of 2010

Brigid Alverson: 2010 The year in digital comics

Brigid Alverson: 2010 The year in piracy

Welcoming in 2011

Douglas Wolk: What we're looking forward to in 2011

Kevin Church: My only resolution for 2011

Sean Gaffney: Manga the Week of 1/5

The Ephemerist: Happy New Year!

Dean Haspiel: Happy New Year

Richard Stevens: Marking Time

Curt Purcell: Fuck both years, old and new

Brigid Alverson: Welcome to 2011

Other

Zack Smith: An Oral History of CAPTAIN MARVEL, Pt 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,

Dan Kanemitsu: How Bill 156 Got Passed

R. Fiore: Another Redheaded Ending, Pt 1, 2

Noah Berlatsky: Odd Superheroine Out

Nicholas Gurewitch: Memorabilia

David Welsh: Pretty maids all in a row

Ben Huber: Yotsuba & Strangers

Ben Huber: Yotsuba & Acorn Park

Dirk Deppey: The Mirror of Male-Love Love

Sean Kleefeld: Say Dat Ain't As Funny As It Looks See

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)