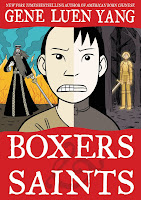

By Gene Luen Yang. Colors by Lark Pien

(Spoilers ahead)

Late 19th century China experienced numerous outbursts of anti-foreign and anti-Christian violence. But it was the incidents in Shendong province that would set the stage for the "Yihequan," (Wade–Giles: I Ho Ch’uan) - sometimes translated into English as "Boxers United in Righteousness” (or alternately “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). This grassroots organisation would inspire, and lend its name to, the mass movement now known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion or Boxer Uprising (1898-1900). After spreading throughout northern China, the Boxers would converge on Beijing and lay siege to the city’s Legation Quarter with the aid of the Imperial Army. This was where foreign expatriates and native converts to Christianity from all over the country sought refuge from the growing violence. But the Boxers would not succeed in ridding China of its foreign presence. Troops from eight nations finally arrived in Beijing, protected the Legations, defeated the Chinese forces, plundered the city and the surrounding countryside, and summarily executed any suspected Boxer. While the immediate repercussions of the Boxer Rebellion were a great calamity, in the long-term their actions would help radically transform the face of China.

What some contemporary Western observers noted about the Yihequan was their unusual method of calisthenics (popularly labelled today as “kung fu”). On the one hand they claimed that they could strengthen their bodies to become immune to the effects of conventional weapons. But the Yihequan also believed that they could channel the gods of legend and popular opera so that they could acquire their mythical powers and abilities in the heat of battle. This kind of magic thinking is rarely taught nowadays to martial arts students. It might even be a source of embarrassment if ever bought up. But it’s the one aspect of the Boxers Gene Luen Yang latches on to as a way to get into their heads. In his latest graphic novel Boxers & Saints, Yihequan magic becomes an all-consuming religious experience equal in power to the mysticism of the Catholic Saints. It’s an idiosyncratic approach that allows him to conveniently sidestep some of the historical complexities while touching on themes of great personal significance.

The comic itself could be described as a comparative study of two kinds of spiritual journeys, mirrored by the two-volume structure. While they could be read separately, they're really meant to complement one another. The first and larger volume focuses on Little Bao, a peasant boy from a small village in Shan-tung province (Yang uses Wade-Giles throughout the comic). Yang simplifies and streamlines the complicated tangle of events that occurred during the Uprising by making the fictional Bao the center of Boxer activity. Unhappy with how foreigners disparage local customs and throw their weight around without fear of reprisal, Bao studies martial arts under itinerant folk hero Red Lantern Chu, learns the magic ritual of spirit possession from an eccentric mountain sage, inspires the youth of his village and others to take up arms against the “foreign devils”, and establishes the “Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist.” In the beginning, Bao’s goal is as clear and simple as it is honorable. But as with so many crusaders, things quickly become muddled the closer he gets to achieving those goals.

The second volume tells the story of an unnamed girl who grew up in an adjacent village, but is treated as an outcast by her own family due to the circumstances of her birth corresponding to the numerically-based superstition that Four is Death. After being labeled a “devil” by her own grandfather, she becomes fascinated with a visiting Christian missionary, as foreigners are often called devils by the locals. Deciding that she has more in common with them than her own family, she attends catechism classes, begins to experience visions of the life of Joan of Arc, converts to Roman Catholicism, and takes the name Vibiana. When she is physically abused for her religious conversion, Vibiana runs away from home. This takes place a few years before Bao instigates the Boxer Rebellion. But as the Rebellion heats up, their two paths eventually intersect.

Of the two, Bao starts out as the more relatable character. He only wants to defend his poor community from those overbearing outsiders. The first act of his story can even be described as an origin tale. His father is attacked by villains, which motivates Bao to seek both revenge and justice. He then acquires a superpower after going through a few trials to prove that he is worthy. Yang’s economic cartooning style keeps everything pretty assessable. When Bao uses spirit possession for the first time, the sky is filled by the presence of various gods dressed in colourful opera regalia, then he himself embodies one of the gods. It’s reminiscent of Billy Batson transforming into Captain Marvel. As coloured by Lark Pien, this transformation provides a stark contrast between the impoverished countryside and the gaudily dressed opera characters.

The problems for Bao begin when he expands his mission from protecting the weak to defending all of China. As the mountain of bodies of not just soldiers and missionaries but also women and children begin to accumulate, Bao is goaded on by the god Ch’in Shih-huang, first emperor of China. Ch’in’s an Old Testament kind of guy, and his message to Bao is unambiguous - He has to be completely ruthless in his war against the foreign devils. But Bao is presented with a paradox. He’s being led on to fight for China by a story. But the longer the war lasts, the more he’s forced to ignore other equally important tales that emphasise compassion and mercy. As he’s reminded during the burning of an ancient library, “…What is China but a people and their stories?” Bao is torn between his patriotism and his humanism, and B&S offers no answer on to how to resolve his internal conflict and fashion a more effective synthesis. The political and personal remain irreconcilable domains, and the Boxers' quest to save China is doomed to failure.

Vibiana’s attraction to Christianity may have been based on less than honourable motives, but this makes her a more well-rounded character. Her lifelong struggles with her adopted faith are in fact perfectly in line with a long tradition of doubting Thomas figures found in Roman Catholicism. Her supporting cast is also largely composed of people struggling with faith each in their own unique way. While Bao’s visions are unambiguous, if terrifying, Vibiana is constantly being led astray by her spiritual communions with Joan. Vibiana speaks to Joan directly, but is often left more confused than enlightened. At one point, she even considers joining the Boxer Uprising since the Boxers seem to parallel Joan’s own military career. Towards the end, Yang weighs the two lives in favour of Vibiana’s more introspective quest over Bao’s more outward expression of belligerence. Faith should never be confused with absolute certainty. And judging from the act of self-sacrifice she performs to help Bao, Vibiana would have probably been at the very least recognised as a martyr by the Church had she existed at the time.

And thanks to that Catholicism, Yang can’t help but engage in the heavy-handed ecumenical tendency to mould the followers of other faiths into Anonymous Christians. In American Born Chinese, he inserted the character of Tze-Yo-Tzuh into the story of the Monkey King as a thinly-disguised Christian analog. In B&S he links the bodhisattva Guan Yin to Jesus Christ. Thankfully, he isn't as emphatic in conveying the message, though the practice can still strike a discordant and not entirely convincing note.

B&S is Yang's most ambitious and complex work to date reflecting his particular worldview. Due to Yang’s peculiar passion for exploring the dimensions of his faith, the comic can often feel like a tangential investigation of the Boxer Uprising and of China itself. Let’s ignore/downplay whatever socio-economic factors contributed to widespread discontent and the rise of the Yihequan, and just imagine that it was an exclusively religious conflict. And who cares that infighting within the Imperial Court and Army hastened the demise of the Boxers. The final panel of B&S is a mournful portrait of Beijing (Peking) being burned to the ground as it's being sacked by foreigners. But as tragic as that all sounds, the war did have the effect of limiting the scope of Western colonialism within the country, and the modern China that would emerge after 1900 has noticeably gone down a far more secular path.