Go to: Drew Weing (via Shaenon Garrity)

7/31/2014

7/27/2014

The Karate Kid (1984)

It’s been said before that 1984 was a really amazing year for the kind of movies that would go on to play an indispensable role in contemporary pop culture. So to celebrate this 30th anniversary, I’m going to ramble on about my personal favourite from that list, The Karate Kid, a movie that has helped forge my individual nerd identity and awareness of how Asia is portrayed in the West.

I was still a kid living half a world away from Hollywood back then, and one of the first things my peers commented on after seeing it was that the karate sucked. A lot of it was blamed on the character of Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio), who starts out as the proverbial 90 lb. weakling, but happens to know a few karate moves, and ends up as a 90 lb. weakling with a few more karate moves under his belt. None of the main cast looked particularly impressive by the standards of traditional martial arts cinema. And yet those awkwardly executed techniques shorn of accompanying acrobatics and complicated stunt work were a curious revelation. TKK debuted during the tail end of the “kung fu” craze and the crest of the even wackier ninja craze. But whether portrayed by Hong Kong or Hollywood, Asian martial arts were still largely set within a pseudo-fantasy world. They had to be taught in monasteries or small villages hidden high within remote mountaintops as far as the movies were concerned (and still are). And they were usually performed by larger-than-life action hero types. But when high school bully Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka) threw an unremarkable front kick at new kid Daniel, causing the latter to keel over in extreme pain, the raw violence drew attention to the fact that many perfectly ordinary teenagers were already practicing martial arts up and down the country and were using those same skills on each other, whether through tournaments such as the one seen in the movie, in the dojo, or on the streets. TKK presented a far more mundane portrait for the Asian martial arts, making it impossible to dismiss them as mere bunk that could only happen in the movies. It wasn't necessary be a f*%#in' Bruce Lee or Sho Kosugi since any dweeb could mosey on down to the nearest class and learn how to "Keith Nash" someone in the nuts.

TKK did still draw from its fair share of classic martial arts tropes, which I quickly picked up on in the style-vs-style clash between the Cobra Kai karate dojo and Keisuke Miyagi (Noriyuki Morita). The former is an analog of Japanese karate, or perhaps more accurately an Americanized freestyle version of it, which emphasizes speed, power, athleticism and forceful movements. On the other hand, Miyagi's surname is a shout out to the Okinawan founder of goju-ryu karate Chōjun Miyagi. In the movie, the students of Cobra Kai were training to execute fast and hard-hitting punching combos with military precision ("Strike first, strike hard, no mercy, sir!") while Daniel was being taught a series of gentle, flowing parries that resembled a bird flapping its wings by carrying out a succession of dull household chores. Just in case anyone watching missed the point, the movie’s signature move is called the “crane technique”, a reference to the White Crane school of Chinese boxing (kung fu), believed to have strongly influenced the local karate traditions the real-life Miyagi studied. This animal symbolism is kind of a big deal to martial artists. For example, the famous sifu Ip Man was probably borrowing from White Crane and Taijiquan folklore when he penned the story of how the legendary figure Ng Moy invented Wing Chun boxing after witnessing a crane taking on a snake. So when puny Daniel mopped the floor with the beefy Cobra Kai members at the “All-Valley KarateTournament”, it’s meant to be a slight dig at modern karate’s extravagance. By practising the older, more "authentic" Okinawan art, Daniel had access to a store of wisdom that emphasized ideas like softness conquering hardness, technique overcoming raw power, and gentleness diffusing aggression. Now, if you could have at the very least told me all of this at the top of your head and still can't wait to tell me more, then congratulations! You're probably a martial arts otaku, or maybe you just had a strict sensei.

I was less able to recognize the geopolitical components since my Asian upbringing left me largely unfamiliar with American history. I wasn’t yet aware that the Vietnam War was a national tragedy for the United States. It would be two years before Oliver Stone’s Platoon taught me how America saw Southeast Asia during the Cold War as some kind of quagmire. And it didn’t occur to me that Cobra Kai head instructor John Kreese's (Martin Kove) “no mercy” philosophy, boot camp style training, mischaracterization of Miyagi’s peace offering as a challenge, and underhanded tactics could be blamed on him being a “Crazy Vietnam Veteran”. If Kreese were a real person alive today, he’d probably blame TKK for contributing to the pussification of America. As for his opposite Miyagi, his membership to the all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Battalion was the first I ever heard of the unit. So it took a bit longer for me to grasp that Kreese vs Miyagi embodied another message: “Vietnam War bad, World War II good.”

Later viewings would impress on me just how much the movie’s subtext comments on Reagan-era America. Behind a superpower bullish of its military prowess (this was the decade when he-man types like Chuck Norris, Stallone and Schwarzenegger would occasionally stomp around the jungles of hapless third world countries) were nagging doubts about the negative impact of US exceptionalism abroad (sometimes manifested in the era's ambivalent media representations of the Vietnam War). And there was a growing suspicion that the country’s prestige would eventually lose to the increasing economic clout of the Far East, especially former enemy Japan, the very country that was turning their kids on to the benefits of fuel-efficient cars and martial arts.

Things have changed a lot since then. While Japanese pop culture has become a staple component for American youth, karate and other forms of budo have lost some of their luster, and Japan itself is downplayed as a threat to American self-interests. The 2010 version recognized China's ascension as the new center of power combined with the growing suspicion that America's best days may already be firmly behind it. So Dre and Sherry Parker would leave the Motor City behind for the rapidly expanding megacity called Beijing in search for a better life.*

But back in 1984, sunny California was still the land of opportunity. So Daniel and his mom Lucille (Randee Heller) uproot themselves from the rustbelt state of New Jersey to seek out new opportunities in San Fernando Valley. Daniel feels immediately out-of-place as if they had moved to Paris, France. Even the more enthusiastic Lucille thinks they’ve alighted on the land of the blondes, confirmed when Daniel catches the eye of the pretty Ali Mills (Elisabeth Shue), then gets into a fight with the equally Aryan-looking Johnny. There’s classism mixed with personal jealousy with an undertow of ethnic rivalry. Both Ali and Johnny come from wealthy families, and there’s no way Johnny is going to lose his ex-girlfriend to some working class, greasy-haired, soccer playing, Italian interloper sporting a thick Joisey accent.**

What has often been described by critics as a coming-of-age tale acquires the features of an assimilationist fantasy when Daniel and Miyagi bond over bonsai trees, and later over karate. Given the murder of Vincent Chin two years earlier, the Miyagi character is a carefully assembled collection of personality traits designed to counter the era’s anti-Japanese xenophobia. The movie takes great pains to point out that he’s more Okinawan than Japanese. He’s a decorated soldier who fought for the Allies while his wife and unborn child were sent to the infamous Manzanar prison camp. And he doesn’t drive a Honda, he owns a fleet of classic cars made in Detroit. “Wax on, wax off” isn’t just good karate training, it’s a patriotic act when used on the proper vehicle. Miyagi is a model citizen who contributes his knowledge to society, in the process Americanizing the Okinawan martial art, through teaching Daniel.

And I’m certainly not the first to point out that Miyagi is basically Yoda - an orientalist image of the exotic-looking, pidgin-speaking, balding, ageing martial arts master counciling his impatient young padawan through the use of pithy (and eminently quotable) statements not to give in to fear, anger and hate.*** If the increasingly ruthless Kreese preaches “Mercy is for the weak. Here, in the streets, in competition. A man confronts you, he is the enemy. An enemy deserves no mercy…” Miyagi instructs Daniel on how karate can be applied to life: “First learn balance. Balance good, karate good, everything good. Balance bad, might as well pack up, go home.” Miyagi symbolically heals the racial rift, first during his youth by serving as a valiant soldier, then later serving as a mentor to the Caucasian Daniel, who then goes on to kick the crap out of his tormentors.

If that last part sounds implausible, that’s because it is. A plot in which a rank amateur learns to beat the experts after training for under 2 months using some very unusual methods of approximation? A comically over-the-top arch villain? The eccentric sensei that embodies every trope of the genre? The old-fashioned notion that you can earn the bully’s respect by beating him up? It’s just as hokey in 2014 as it was back in 1984. And yet, it still kind of works. The movie’s interactions still sound fresh and genuine, and the generally excellent cast inhabits their characters with utter conviction. Miyagi in particular could have been a dud, but Morita’s nuanced performance keeps the character from turning into another dull stereotype. Instead, what comes across is the warmth and humour from an actual person. That scene where Miyagi drunkenly re-enacts his own shocked reaction to the news of how his wife and child died during childbirth is surprisingly gut-wrenching even after 30 years. Macchio and Morita have an undeniable onscreen camaraderie that emotionally anchors the movie, but even the supporting characters come off pretty well despite being given little screen time (Needless to say, the story doesn't pass the Bechdel Test). What I particularly liked when I viewed TKK for this post were the scenes between Macchio and Heller, as they have the kind of relaxed verbal exchanges expected from a single mother and her teenage son.

If any character threatens to unbalance the movie, it’s the hissing, sneering, swaggering Kreese. His all-consuming hatred for everything weak doesn’t rise above the level of classic pulp villainy. When he instructs one of his students to put Daniel “out of commission”, I could practically see him twirl a virtual moustache. The character feels like he stepped out from the kind of movie which would have featured a s#@tload of guns and the requisite zombie horde. But then again, Kove also plays him as such an amusingly detestable human being that he raises the stakes and energizes every scene he’s in. So if Miyagi is Yoda, then I guess this makes Kreese a sandy-haired, musclebound Emperor Palpatine.

Taking advantage of its gorgeous backdrops, TKK is a delightful visual treat. It also helps that 80s Southern California looks positively wholesome and innocent from the perspective of a 30 year gap. The same could be said about the cinematography. In contrast to the frenetic pacing and busy camerawork of today’s movies, TKK’s pacing is leisurely, especially the iconic middle section where Daniel and Miyagi hunker down to train. It’s all about the journey as Daniel learns to wax the cars, sand the floor, and paint the house. I found myself still taken in by the surrounding natural beauty of Leo Carillo Beach where Daniel tries to master the crane technique, even though the smart-ass within me is irked that all he’s doing is clumsily attempting a stylized jumping front kick. On the other hand, the climactic tournament scenes are surprisingly brisk by today’s standards. The famous fight montage set to the corny youth anthem “You’re the Best” by Joe Esposito is a marvel of simplicity that efficiently conveys the necessary information. The final freeze frame of Miyagi smiling at the camera might seem almost too abrupt. Wouldn’t a Michael Bay have shown Daniel and Ali sharing a passionate kiss while the enraptured crowd swells around the two, accompanied by an exploding fireworks display in the background synchronised to a booming power chord progression played on an electric guitar, and Kreese being arrested for paederasty to the jeers of his now former students? God, how I hate the Transformers.

Like many youth-oriented movies from the 80s, TKK is sincere with its message, lacking in irony, and devoid of any self-aware winking at the audience or clever metatextual devices. It's unlikely that this movie would have been shot today, unless you count the 2010 remake. And its producers felt compelled to lower the age of its characters from teenage adolescents to tweens in order to make the story more plausible to current fans. TKK quickly spawned a bunch of Hollywood imitators using similar plot devices: The persecuted and inept White hero, the Oriental master, the training montage, the tournament as showdown. But none of them could follow the original’s advice and find the delicate balance between the hokier elements and the human drama. When Bloodsport came out 4 years later, the genre had already moved away from the adventures of an affable pipsqueak. The cheesy fantasy and the strongmen had made their way back, although in truth they never really left. This was still the 80s, after all. Come to think of it, the closest thing I've recently watched on television which reminded me of the spirit of TKK was Dodgeball. "If you can dodge a wrench, you can dodge a ball" is so "Paint the fence".

One thing that stands out after 30 years is how much the movie encapsulates a shift in the East-West exchange. Karate and other martial arts had traditionally been associated with the counterculture in the West, along with a host of other Asian cultural imports. But by the 80s these "traditions" were being co-opted by the mainstream. With that, the mystique surrounding them, as well as the belief in their authenticity, was perhaps irretrievably lost. By the end of the decade the orientalist image of the little Asian master was being forced to share face time with the CEO quoting from The Book of Five Rings and The Art of War. The sensei running the average dojo was more likely to resemble John Kreese than Mr. Miyagi. Dojos had to be run smartly, just as any other successful business. And its members would ineluctably include more well-heeled yuppies made from the same mould as Johnny Lawrence and Ali Mills. Martial arts had progressed from being underground knowledge to just another consumer good sold on the open market. The promise of personal liberation fetishized and reshaped to better fit into the economic system. When Daniel LaRusso rejected the expensive, efficiently run, but inhumane Cobra Kai dojo only to form a tightly knit teacher-student bond with Miyagi, TKK was applying no more than the mildest social critique against this trend. That the martial arts could mirror the broader friction between mainstream and marginal might actually have been the movie's most prescient insight. But within our present media landscape where Asian culture is more ubiquitous, commodified, and fragmented than ever before, and where the most prevalent modes of martial art displays have morphed into the public spectacles of hyper-real combat sports, TKK's gentle admonitions are just as likely to evoke nostalgia from the general audience.

Oh well. I'll just finish this post with a panel of the original Karate Kid taking down a slithery Superboy, because Val Armorr is the boss!

_____ *The Chinese title for the 2010 Karate Kid translates as Kung Fu Dream, a much more literal description since Japanese and Okinawan culture plays no significant role in the movie.

**While I wasn’t initially impressed with the 2010 remake, I did like how the casting of Jaden Smith is a nod to how Asian martial arts have played a huge role in African-American life. The dearth of African-Americans (and other people of color) in the 1984 original is a much bigger omission when watched in 2014. How would the movie have turned out if Daniel LaRusso were cast as Black?

*** Interestingly, the stylistic clash between the Sith-controlled Galactic Empire and the Jedi-inspired Rebel Alliance in the Star Wars film series has been described as an allegory of the Vietnam War.

7/23/2014

7/18/2014

Technical Problems

7/10/2014

Webcomic: Trigger Warning: Breakfast

Go to: The Nib (via Heidi MacDonald)

7/07/2014

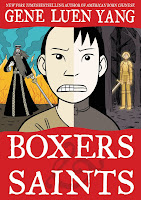

Martial Myths: Boxers & Saints

By Gene Luen Yang. Colors by Lark Pien

(Spoilers ahead)

Late 19th century China experienced numerous outbursts of anti-foreign and anti-Christian violence. But it was the incidents in Shendong province that would set the stage for the "Yihequan," (Wade–Giles: I Ho Ch’uan) - sometimes translated into English as "Boxers United in Righteousness” (or alternately “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). This grassroots organisation would inspire, and lend its name to, the mass movement now known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion or Boxer Uprising (1898-1900). After spreading throughout northern China, the Boxers would converge on Beijing and lay siege to the city’s Legation Quarter with the aid of the Imperial Army. This was where foreign expatriates and native converts to Christianity from all over the country sought refuge from the growing violence. But the Boxers would not succeed in ridding China of its foreign presence. Troops from eight nations finally arrived in Beijing, protected the Legations, defeated the Chinese forces, plundered the city and the surrounding countryside, and summarily executed any suspected Boxer. While the immediate repercussions of the Boxer Rebellion were a great calamity, in the long-term their actions would help radically transform the face of China.

What some contemporary Western observers noted about the Yihequan was their unusual method of calisthenics (popularly labelled today as “kung fu”). On the one hand they claimed that they could strengthen their bodies to become immune to the effects of conventional weapons. But the Yihequan also believed that they could channel the gods of legend and popular opera so that they could acquire their mythical powers and abilities in the heat of battle. This kind of magic thinking is rarely taught nowadays to martial arts students. It might even be a source of embarrassment if ever bought up. But it’s the one aspect of the Boxers Gene Luen Yang latches on to as a way to get into their heads. In his latest graphic novel Boxers & Saints, Yihequan magic becomes an all-consuming religious experience equal in power to the mysticism of the Catholic Saints. It’s an idiosyncratic approach that allows him to conveniently sidestep some of the historical complexities while touching on themes of great personal significance.

The comic itself could be described as a comparative study of two kinds of spiritual journeys, mirrored by the two-volume structure. While they could be read separately, they're really meant to complement one another. The first and larger volume focuses on Little Bao, a peasant boy from a small village in Shan-tung province (Yang uses Wade-Giles throughout the comic). Yang simplifies and streamlines the complicated tangle of events that occurred during the Uprising by making the fictional Bao the center of Boxer activity. Unhappy with how foreigners disparage local customs and throw their weight around without fear of reprisal, Bao studies martial arts under itinerant folk hero Red Lantern Chu, learns the magic ritual of spirit possession from an eccentric mountain sage, inspires the youth of his village and others to take up arms against the “foreign devils”, and establishes the “Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist.” In the beginning, Bao’s goal is as clear and simple as it is honorable. But as with so many crusaders, things quickly become muddled the closer he gets to achieving those goals.

The second volume tells the story of an unnamed girl who grew up in an adjacent village, but is treated as an outcast by her own family due to the circumstances of her birth corresponding to the numerically-based superstition that Four is Death. After being labeled a “devil” by her own grandfather, she becomes fascinated with a visiting Christian missionary, as foreigners are often called devils by the locals. Deciding that she has more in common with them than her own family, she attends catechism classes, begins to experience visions of the life of Joan of Arc, converts to Roman Catholicism, and takes the name Vibiana. When she is physically abused for her religious conversion, Vibiana runs away from home. This takes place a few years before Bao instigates the Boxer Rebellion. But as the Rebellion heats up, their two paths eventually intersect.

Of the two, Bao starts out as the more relatable character. He only wants to defend his poor community from those overbearing outsiders. The first act of his story can even be described as an origin tale. His father is attacked by villains, which motivates Bao to seek both revenge and justice. He then acquires a superpower after going through a few trials to prove that he is worthy. Yang’s economic cartooning style keeps everything pretty assessable. When Bao uses spirit possession for the first time, the sky is filled by the presence of various gods dressed in colourful opera regalia, then he himself embodies one of the gods. It’s reminiscent of Billy Batson transforming into Captain Marvel. As coloured by Lark Pien, this transformation provides a stark contrast between the impoverished countryside and the gaudily dressed opera characters.

The problems for Bao begin when he expands his mission from protecting the weak to defending all of China. As the mountain of bodies of not just soldiers and missionaries but also women and children begin to accumulate, Bao is goaded on by the god Ch’in Shih-huang, first emperor of China. Ch’in’s an Old Testament kind of guy, and his message to Bao is unambiguous - He has to be completely ruthless in his war against the foreign devils. But Bao is presented with a paradox. He’s being led on to fight for China by a story. But the longer the war lasts, the more he’s forced to ignore other equally important tales that emphasise compassion and mercy. As he’s reminded during the burning of an ancient library, “…What is China but a people and their stories?” Bao is torn between his patriotism and his humanism, and B&S offers no answer on to how to resolve his internal conflict and fashion a more effective synthesis. The political and personal remain irreconcilable domains, and the Boxers' quest to save China is doomed to failure.

Vibiana’s attraction to Christianity may have been based on less than honourable motives, but this makes her a more well-rounded character. Her lifelong struggles with her adopted faith are in fact perfectly in line with a long tradition of doubting Thomas figures found in Roman Catholicism. Her supporting cast is also largely composed of people struggling with faith each in their own unique way. While Bao’s visions are unambiguous, if terrifying, Vibiana is constantly being led astray by her spiritual communions with Joan. Vibiana speaks to Joan directly, but is often left more confused than enlightened. At one point, she even considers joining the Boxer Uprising since the Boxers seem to parallel Joan’s own military career. Towards the end, Yang weighs the two lives in favour of Vibiana’s more introspective quest over Bao’s more outward expression of belligerence. Faith should never be confused with absolute certainty. And judging from the act of self-sacrifice she performs to help Bao, Vibiana would have probably been at the very least recognised as a martyr by the Church had she existed at the time.

And thanks to that Catholicism, Yang can’t help but engage in the heavy-handed ecumenical tendency to mould the followers of other faiths into Anonymous Christians. In American Born Chinese, he inserted the character of Tze-Yo-Tzuh into the story of the Monkey King as a thinly-disguised Christian analog. In B&S he links the bodhisattva Guan Yin to Jesus Christ. Thankfully, he isn't as emphatic in conveying the message, though the practice can still strike a discordant and not entirely convincing note.

B&S is Yang's most ambitious and complex work to date reflecting his particular worldview. Due to Yang’s peculiar passion for exploring the dimensions of his faith, the comic can often feel like a tangential investigation of the Boxer Uprising and of China itself. Let’s ignore/downplay whatever socio-economic factors contributed to widespread discontent and the rise of the Yihequan, and just imagine that it was an exclusively religious conflict. And who cares that infighting within the Imperial Court and Army hastened the demise of the Boxers. The final panel of B&S is a mournful portrait of Beijing (Peking) being burned to the ground as it's being sacked by foreigners. But as tragic as that all sounds, the war did have the effect of limiting the scope of Western colonialism within the country, and the modern China that would emerge after 1900 has noticeably gone down a far more secular path.

(Spoilers ahead)

Late 19th century China experienced numerous outbursts of anti-foreign and anti-Christian violence. But it was the incidents in Shendong province that would set the stage for the "Yihequan," (Wade–Giles: I Ho Ch’uan) - sometimes translated into English as "Boxers United in Righteousness” (or alternately “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”). This grassroots organisation would inspire, and lend its name to, the mass movement now known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion or Boxer Uprising (1898-1900). After spreading throughout northern China, the Boxers would converge on Beijing and lay siege to the city’s Legation Quarter with the aid of the Imperial Army. This was where foreign expatriates and native converts to Christianity from all over the country sought refuge from the growing violence. But the Boxers would not succeed in ridding China of its foreign presence. Troops from eight nations finally arrived in Beijing, protected the Legations, defeated the Chinese forces, plundered the city and the surrounding countryside, and summarily executed any suspected Boxer. While the immediate repercussions of the Boxer Rebellion were a great calamity, in the long-term their actions would help radically transform the face of China.

What some contemporary Western observers noted about the Yihequan was their unusual method of calisthenics (popularly labelled today as “kung fu”). On the one hand they claimed that they could strengthen their bodies to become immune to the effects of conventional weapons. But the Yihequan also believed that they could channel the gods of legend and popular opera so that they could acquire their mythical powers and abilities in the heat of battle. This kind of magic thinking is rarely taught nowadays to martial arts students. It might even be a source of embarrassment if ever bought up. But it’s the one aspect of the Boxers Gene Luen Yang latches on to as a way to get into their heads. In his latest graphic novel Boxers & Saints, Yihequan magic becomes an all-consuming religious experience equal in power to the mysticism of the Catholic Saints. It’s an idiosyncratic approach that allows him to conveniently sidestep some of the historical complexities while touching on themes of great personal significance.

The comic itself could be described as a comparative study of two kinds of spiritual journeys, mirrored by the two-volume structure. While they could be read separately, they're really meant to complement one another. The first and larger volume focuses on Little Bao, a peasant boy from a small village in Shan-tung province (Yang uses Wade-Giles throughout the comic). Yang simplifies and streamlines the complicated tangle of events that occurred during the Uprising by making the fictional Bao the center of Boxer activity. Unhappy with how foreigners disparage local customs and throw their weight around without fear of reprisal, Bao studies martial arts under itinerant folk hero Red Lantern Chu, learns the magic ritual of spirit possession from an eccentric mountain sage, inspires the youth of his village and others to take up arms against the “foreign devils”, and establishes the “Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist.” In the beginning, Bao’s goal is as clear and simple as it is honorable. But as with so many crusaders, things quickly become muddled the closer he gets to achieving those goals.

The second volume tells the story of an unnamed girl who grew up in an adjacent village, but is treated as an outcast by her own family due to the circumstances of her birth corresponding to the numerically-based superstition that Four is Death. After being labeled a “devil” by her own grandfather, she becomes fascinated with a visiting Christian missionary, as foreigners are often called devils by the locals. Deciding that she has more in common with them than her own family, she attends catechism classes, begins to experience visions of the life of Joan of Arc, converts to Roman Catholicism, and takes the name Vibiana. When she is physically abused for her religious conversion, Vibiana runs away from home. This takes place a few years before Bao instigates the Boxer Rebellion. But as the Rebellion heats up, their two paths eventually intersect.

Of the two, Bao starts out as the more relatable character. He only wants to defend his poor community from those overbearing outsiders. The first act of his story can even be described as an origin tale. His father is attacked by villains, which motivates Bao to seek both revenge and justice. He then acquires a superpower after going through a few trials to prove that he is worthy. Yang’s economic cartooning style keeps everything pretty assessable. When Bao uses spirit possession for the first time, the sky is filled by the presence of various gods dressed in colourful opera regalia, then he himself embodies one of the gods. It’s reminiscent of Billy Batson transforming into Captain Marvel. As coloured by Lark Pien, this transformation provides a stark contrast between the impoverished countryside and the gaudily dressed opera characters.

The problems for Bao begin when he expands his mission from protecting the weak to defending all of China. As the mountain of bodies of not just soldiers and missionaries but also women and children begin to accumulate, Bao is goaded on by the god Ch’in Shih-huang, first emperor of China. Ch’in’s an Old Testament kind of guy, and his message to Bao is unambiguous - He has to be completely ruthless in his war against the foreign devils. But Bao is presented with a paradox. He’s being led on to fight for China by a story. But the longer the war lasts, the more he’s forced to ignore other equally important tales that emphasise compassion and mercy. As he’s reminded during the burning of an ancient library, “…What is China but a people and their stories?” Bao is torn between his patriotism and his humanism, and B&S offers no answer on to how to resolve his internal conflict and fashion a more effective synthesis. The political and personal remain irreconcilable domains, and the Boxers' quest to save China is doomed to failure.

Vibiana’s attraction to Christianity may have been based on less than honourable motives, but this makes her a more well-rounded character. Her lifelong struggles with her adopted faith are in fact perfectly in line with a long tradition of doubting Thomas figures found in Roman Catholicism. Her supporting cast is also largely composed of people struggling with faith each in their own unique way. While Bao’s visions are unambiguous, if terrifying, Vibiana is constantly being led astray by her spiritual communions with Joan. Vibiana speaks to Joan directly, but is often left more confused than enlightened. At one point, she even considers joining the Boxer Uprising since the Boxers seem to parallel Joan’s own military career. Towards the end, Yang weighs the two lives in favour of Vibiana’s more introspective quest over Bao’s more outward expression of belligerence. Faith should never be confused with absolute certainty. And judging from the act of self-sacrifice she performs to help Bao, Vibiana would have probably been at the very least recognised as a martyr by the Church had she existed at the time.

And thanks to that Catholicism, Yang can’t help but engage in the heavy-handed ecumenical tendency to mould the followers of other faiths into Anonymous Christians. In American Born Chinese, he inserted the character of Tze-Yo-Tzuh into the story of the Monkey King as a thinly-disguised Christian analog. In B&S he links the bodhisattva Guan Yin to Jesus Christ. Thankfully, he isn't as emphatic in conveying the message, though the practice can still strike a discordant and not entirely convincing note.

B&S is Yang's most ambitious and complex work to date reflecting his particular worldview. Due to Yang’s peculiar passion for exploring the dimensions of his faith, the comic can often feel like a tangential investigation of the Boxer Uprising and of China itself. Let’s ignore/downplay whatever socio-economic factors contributed to widespread discontent and the rise of the Yihequan, and just imagine that it was an exclusively religious conflict. And who cares that infighting within the Imperial Court and Army hastened the demise of the Boxers. The final panel of B&S is a mournful portrait of Beijing (Peking) being burned to the ground as it's being sacked by foreigners. But as tragic as that all sounds, the war did have the effect of limiting the scope of Western colonialism within the country, and the modern China that would emerge after 1900 has noticeably gone down a far more secular path.

7/02/2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)