Artist: Stan Sakai

Colors: Lovern Kindzierski

Letters: Tom Orzechowski, Lois Buhalis

“To know the story of the 47 Ronin is to know Japan.” says the tag line to this retelling of an oft-repeated tale. Which brings up a salient question. Don't we already know Japan through this narrow perspective? Before the country was known to the West as the land of cosplay-obsessed otaku, it was more traditionally known as the land of honor-obsessed warriors. This image was fueled for decades by a long line of works for popular entertainment, such as the best-selling novel Shogun or the more recent film The Last Samurai. They're primarily distortions of history which helped feed into some very powerful and longstanding racial stereotypes. But I suppose nothing beats the original, home-grown product to get the point across. There's something to be said about not seeing Japan again filtered through the actions of another bewildered-looking gaijin.

The actual events go something like this: a young daimyo named Asano Naganori used his sword to attack the elderly court official Kira Yoshihisa (Yoshinaka) within the grounds of Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi's palace when its staff was busy dealing with an official visit from the Emperor's envoys. The exact nature of Asano's grievance with Kira has never been definitively pinpointed. But he failed to land a killing blow. And for his rash actions, Asano was quickly sentenced to death by the Shogun, his lands seized, and his family dispossessed. In response to this severe punishment, over forty of Asano's most faithful (but now masterless) bushi led by chief retainer Oishi Kuranosuke hatched a plan to complete the job. They bided their time for almost two years. Then on a cold winter night they raided Kira's house, slaughtered his servants, and took his life. The ronin carried Kira's head to Asano's grave at Sengakuji temple as an offering. There they waited for the Shogun's judgement, who stayed true to form and condemned them all to death.

Kira's murder was extremely controversial to its contemporaries,* but it also captured the public's imagination. The event would be retold many times, with further details added and embellished. In what could be thought of as a case of blaming the victim, Kira was vilified in future versions as a cowardly figure who provoked the noble Asano into attacking him, while the criminal behavior of the 47 ronin (the number of retainers finally settled on) was justified by the code of bushido, making them the embodiment of the virtues of duty, honor, and loyalty. When the office of the shogun was finally abolished, the tale acquired the status of patriotic myth within a rapidly modernizing Japan.

For all the years of supposed research and trips to Japan, Mike Richardson has chosen mythical retelling over history, which when taken on its own terms is a valid storytelling option. The tale has a certain noire appeal with its band of would-be criminals defying the law in order to follow a more violent personal code. Besides, who doesn't like to see the underdog overcome the odds to beat the high and mighty, or at least die trying? And on a more universal level, it's a rousing, manly tale of good vs. evil.

If there's a weakness with his version, it's the cut-and-dried quality of the narrative. The characterizations are archetypical: Kira is vain, corrupt, greedy, and vindictive. Asano is unpretentious, noble, a devoted family man, and righteous. Oishi is loyal to a fault. The pacing is a steady slow-burning dramatic arc. Part one is devoted to building up the conflict between Asano and Kira, while part two focuses on the palace intrigue leading up to Asano's execution. Dates and place names are clearly labelled with captions. And everyone, even the kids, talks in a very formal manner, which sometimes makes me wonder if Mike was trying to mimic the language of classical Japanese theater.

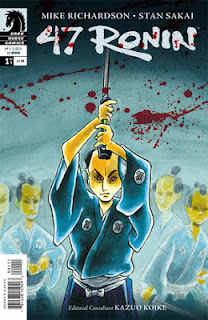

An artist with more baroque, sensuous, or dynamic sensibilities could have probably served to better counteract the stiffness of the script. Sadly, this job isn't quite suited to Stan Sakai. I can see why Mike describes him in the afterword as the right artist for the comic. He's a brilliant cartoonist, and he respects the setting of the story. Probably more than most artists. There's nothing exaggerated or manifestly inaccurate about his portrayal of 18th century Japan. This is clearly a labour of love for Mike. But I still feel that Stan's style would have better complimented a more satirical retelling of the myth. Mike's approach is too humorless and reverent to completely mesh with Stan's whimsical style.

Two issues into its five part run, this is a agreeable, if not wholly original, exploration of well-trod territory. It's fairly conventional and somewhat flat, and would be even duller if not for some lovely details supplied by Stan's amazing work. But so far, there's just a dearth of energy which leaves me underwhelmed.

___

* The samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo questioned the motives of Oishi's group when he wrote this passage in the Hagakure:

"Concerning the night assault of Lord Asano’s ronin, the fact that they did not commit seppuku at the Sengakuji was an error, for there was a long delay between the time their lord was struck down and the time when they struck down the enemy. If Lord Kira had died of illness within that period, it would have been extremely regrettable."Strongly implying that the underhanded methods used in the revenge plot exhibited far less honorable motives than had the ronin promptly and openly challenged Kira after Asano's execution.