Go to: Homeopathy by Darryl Cunningham

6/30/2010

6/28/2010

Slideshow: Toycon 2010

My digital tools have been failing me lately. The computer is old, so that's understandable. But even newer equipment like my Cintiq and my DSLR have been malfunctioning. If the computer goes... I guess I'll have to get a new one. Duh.

Go to: Flickr Album

6/25/2010

6/22/2010

Prince of Persia: The Graphic Novel

By Jordan Mechner, A.B. Sina, LeUyen Pham, Alex Puvilland, Hilary Sycamore

When First Second published a graphic novel adaptation of The Prince of Persia back in 2008, I didn't give it much attention. The original video game, like many other games, had only a skeleton of a story from which to hang its 2D action scenes. The player spends virtually all of the alloted time scampering around an impossibly large, maze-like, palatial interior while dueling haphazardly stationed guards, and avoiding booby traps. Even the graphic novel's original cover, dominated by a robust-looking running figure, gave the not-quite correct impression that it was a heroic action-adventure in the spirit of the original material. I'm unfamiliar with subsequent versions of the franchise, but the narrative contained within the comic is complex, deliberate, and not quite as swashbuckling as its video game origins would suggest.

The video game's creator Jordan Mechner seems to have limited his creative involvement to approving the efforts of writer A.B. Sina, and collaborating artists LeUyen Pham and Alex Puvilland. This wife and husband team draw in a wonderfully expressive style that' seems more influenced by Euro-comics, children's book illustration, and animation. Rather than the overwrought figures found in mainstream fantasy illustration and used to package the games themselves, the graphic novel's characters posses an easily approachable, down-to-earth charm. The art's simplicity offsets the intricacies of a plot that jumps back and forth between two time periods separated by 400 years, each with its own set of characters. Both are tied together by themes like the power of legend, the circularity of history, and the immutability of human nature. Oftentimes the four alchemical elements are used to reinforce them. That's quite a lot to hang on what's basically a dashing tale about heroes battling the machinations of would-be tyrants.

Pham and Puvilland eschew the more obvious devices that could have been used to delineate the two periods. They aren't drawn in contrasting graphic styles. They don't use clear chapter or page breaks to announce the shift in setting. The settings themselves look and feel very similar despite the centuries separating them. The transitions take place between adjacent panels and are only noticeable through small alterations in their details. The layout is also fairly conservative, favoring three to four tiered pages, with single-page panels to punctuate key moments. This makes the shift between the 9th and 13th centuries so seamless as to be almost unnoticeable. A rushed reading of the book will inevitably lead to a great deal of confusion. Colorist Hilary Sycamore paints the later period in more subdued hues using a blue-pink palette, and the earlier period with more saturated colors predominated by reds and oranges. This only partially helps the reader. As the story develops, the two periods begin to resemble each other more and more, especially in the later parts of the book when a prophecy explicitly connects the two casts of characters to each other.

Fans who come to the graphic novel expecting it to be more like the video game or the more recent movie adaptation might come away from it disappointed. In trying to balance the lighthearted romance of the original concept with the scope of its own ambitions, it never achieves the status of an epic. Still, this is far more rewarding than I would have expected from most media tie-ins. If nothing else, I'm looking forward to Pham and Puvilland's next comic book project.

6/21/2010

6/17/2010

Flash Gordon Memories of Al Williamson

I used to own a copy of this story as a kid. It may have been a a Filipino re-print edition. Sadly, it was lost, as with all my childhood comic books, probably when my family was moving house. If I recall correctly, the setting of the story moved from Mingo City to the kingdom of Frigia. Flash and Queen Fria (?) don those funky see-through ski suits to go hunting for ice serpents, or something. Cool, but impractical. And as good an excuse as any to showcase Al's artistic talents with the human form.

6/16/2010

6/14/2010

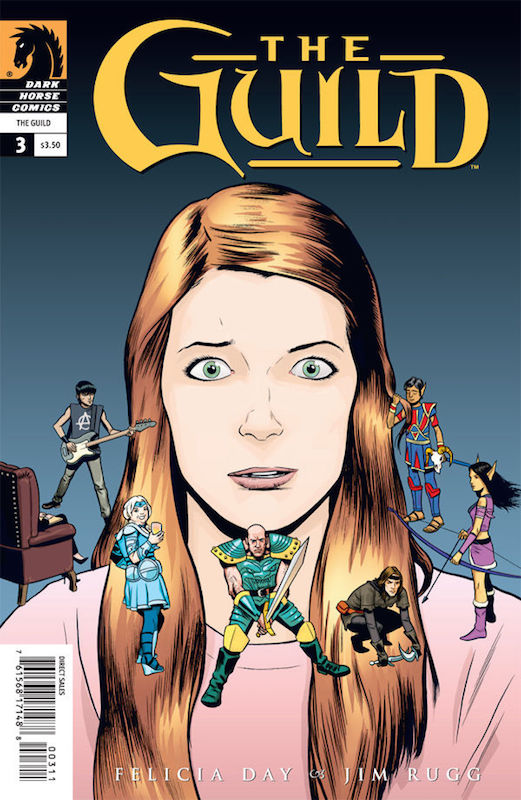

The Guild #2-3

By Felicia Day, Jim Rugg, Dan Jackson, Nate Piekos, Matthew Stawicki, Kristian Donaldson, Juan Ferreyra.

Issues 2 and 3 of The Guild complete the prequel to the successful cult web series. Main protagonist Cyd Sherman's involvement with the online game deepens; she becomes emotionally isolated from the real world; the rest of the cast is assembled; and the story leaves off where the series begins. As I said in my review of the first issue, the comic is best appreciated by pre-existing fans. The deterioration of Cyd's relationship with her boyfriend is alluded to in the first few episodes of the series. And the comic contains in-jokes and references that will go over the heads of non-fans. The supporting characters that comprise her online friends aren't fleshed out enough within the pages of the comic, as they're written as a collection of quirks that fans will easily recognize and proceed to fill in the blanks.* But I'm not sure if most first time readers will understand why Cyd would actually enjoy hanging out with them.

It is through Cyd that Felicia Day most effectively demonstrates the charm and wit of her writing. Cyd is largely portrayed as a sympathetic, if hapless, individual unable or unwilling to confront her manipulative boyfriend. Every real world disappointment prompts her to dive deeper into the fantasy world. Unlike the series, the comic illustrates more of the game's environment. This allows the visuals of the story to break up the monotony of looking at a series of talking heads staring into computer monitors. But even with this device, Day still prefers to largely tell the story through words. The combat sequences are minimally and perfunctorily staged, and tend to rehash Cyd's voice-over narrative. Day's panels are usually filled with dialogue, which isn't necessarily a problem in itself. But the virtual setting feels comparatively cramped and generic. While every character has an easily identifiable in-game avatar, it's really the verbal back and forth that animates them, and helps distinguish them from each other.

Of course, in the web series, the characters are brought to life by actors who have the advantage of being able to deliver their lines. Within the pages of a comic book though, Day's writing falls a bit flat. I don't get the impression that artist Jim Rugg possesses the necessary chops to pace her dialogue in a way that approaches the timing of the live casts' performance, especially Day's. But the page limitations presented by a three issue story doesn't exactly give either him of Day sufficient space to juggle half a dozen eccentric personalities. So while the fans are going to get the story's in-jokes, they're also likely to come away feeling disappointed with it for not being as funny as the web series.

At the end of the day, The Guild comic doesn't function as a stand-alone story. Whatever the weaknesses of the art, or faults found within the writing due to Day's own inexperience with the comics medium, they aren't glaring enough to damage the popularity of the series. If the comic points people towards the main body of work, it's arguably done it's job.

__

* Admitedly, that's how they started out within the series.

6/10/2010

6/09/2010

6/07/2010

6/06/2010

Wilson

The titular character (It's not indicated if Wilson is his given name or surname) would be a much more difficult person to stomach if not for the comic's structure. Wilson is organized as a series of one-page gag strips, each designed to deliver a withering punch line. Wilson begins the story by happily proclaiming his love for his fellow human beings. But his misanthropic personality soon becomes obvious. In the early strips, Wilson accosts complete strangers by engaging in conversation with them. At first he appears genuinely interested. However it soon becomes apparent that he doesn't care about them except as a convenient target for his ridicule. Wilson casts his net far and wide. He cuts some people off for talking too much. He bullies others for refusing to converse with him. He disses their jobs, the vehicles they drive, their taste in movies, or their religious beliefs. Like Charlie Brown futilely trying to kick that football out of Lucy's hands, Wilson seems driven by the need to reach out to other people. But he's unable to connect with them due to an inability to suppress his inner critic. He's the type that doesn't suffer fools gladly. However, he takes it to such an extreme that just about anything someone else says, or doesn't say, can set him off. No wonder he's unemployed and friendless, not counting his pet dog.

The gag strip format allows readers to absorb the character in easily manageable bits. Even so, seventy one pages of Wilson sneering at random people would grow quickly tiresome and repetitive. At first unnoticeable though is that with each succeeding page, a story emerges as circumstances force Wilson to interact with family members. First he's called to the bedside of his dying father. Then he attempts to reconnect with his ex-wife. And then he searches for a daughter he never knew he had. The social ineptitude that drove people away from him has far more painful consequences as Wilson's takes more active steps to re-establish his familial bonds. But the gap between his ideals and reality is vast since the people who know him best have already grown weary of his overly critical attitude. If Wilson were a straightforward family melodrama, this would be a character flaw that he would have to confront and overcome in order to earn the audience's sympathy. A convenient explanation could then be tossed in to account for its origins. Rather, Clowes adherence to the gag strip formula keeps the reader at arm's length from the character. While Wilson does become more miserable, pathetic, and earnest in his goal to find love and acceptance as the story progresses, he remains a comic figure who elicits some disdain, if for nothing else, for all the misery he inflicts on those around him. Wilson doesn't transcend his assigned role until, perhaps, the story's very last panel. Nevertheless, it's an oddly effective way to hold the reader's attention.

Perhaps the most conspicuous feature of the book is that every page is marked by a change in graphic style. Clowes utilizes the full gamut of his craft: from realistic character renderings, to classic big foot cartooning. He colors range from grays, his preferred blue-greenish duotone, to his subdued four color palette. While the play of styles is clever and amusing on its own terms, I'm not sure they represent anything deeper than Clowes just having fun with different approaches, or his way to keep things interesting to him. They don't seem to represent any logical schema. But they're not annoyingly random either. Rather, they're all unified by an underlying organic approach. The quality of his line doesn't vary significantly. His instinctive color combinations remain consistent. And Wilson's visual identity has a way of carrying over through each stylistic shift.

Because Wilson is a deeply irritating character, the book is unlikely to become a fan favorite. Given the all-encompassing nature of his ire, many will find something to dislike about him. But the emotional distance afforded by the technique Clowes employs makes the character easier to witness. The incremental revelation of personal information with each page is both highly entertaining and hugely riveting. Sure, Wilson might be the world's biggest prick. But he's also the overweening ego, found to varying degrees, within all of us.

6/01/2010

Birthdays and Anniversaries

Autographed copy of the Comic-Con International 2001 Souvenir Book. Art and characters by Jeff Smith.

It used to be you could essentially not plan for Comic-Con and just go if the mood struck you. This was true just a few years ago. Those days are gone.

- Tom Spurgeon

I was for a short period a regular attendee of Comic-Con International - when it was still possible to show-up without pre-registering or even booking a hotel. In fact I've only pre-registered just once for any comics related event in the United States. I'm one of those who utter "San Diego" and "Comic-Con" in the same breadth. Back then, I thought that Comic-Con was positively humongous. The crowd was already straining against the walls of San Diego's convention center. Hollywood was making an even bigger imprint on the event's identity. Comics was becoming mainstream. And manga was fast developing into a seemingly unstoppable force. But for me, Comic-Con wasn't just an excuse to skip work and geek out, it became something of an annual celebration, of a more personal nature.

Things have changed a lot since I was last there. Circumstances prevent me from attending Comic-Con for the forseeable future. And I don't stress about it. But if Comic-Con's organizers decide to leave San Diego, part of me will sorely regret not going by 2012.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)