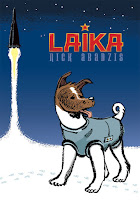

Laika's story is the perfect hook to get children to read more about history. It's also an incredibly obvious example of how animals are often sacrificial offerings to the greater glory of man. The man in this case is Sergei Pavlovich Korolev - leader of the Soviet Union's space program. The book opens with him just released from the Gulag in the dead of winter. With no food and shelter, he keeps motivating himself to stay alive by repeating "I am a man of destiny. I will not die." Korolev's subsequent success in building the USSR's space program confirm his personal self-belief. But these also generate unrealistic higher expectations, which inexorably lead to him developing the project that would top all others - launching the world's first living space explorer.

While the repressive nature of the Soviet Union is alluded to, author Nick Abadzis concentrates on the personal rather than the political or scientific. As the dogs in the program were strays, there's no way to know the details of Kudryavka's (Laika's original name) background. So Abadzis fashions a fictional story full of the usual cliches about abandoned puppies, abusive masters, and sadistic dog catchers. It's clearly there to evoke compassion for the protagonist. But once she falls into the ownership of the government's space program, the story markedly improves. Several new characters take center stage: Oleg Georgivitch Gazenko, the person in charge of animal training, and his assistant Yelena Alexandrovna Dubrovsky. Both Oleg's personal dislike and resentment towards the overbearing Korolev, and Yelena's empathy towards her animal charges express doubt about the program's methods, and give voice to the otherwise mute test subjects. The stress caused by working on the project is further ramped up by the unspoken romantic tension between the two. In contrast Korolev, historically the most important figure, is comparatively less well developed.

Abadzis draws in a shorthand which, depending on readers tastes, is either somewhat incomplete and lacking, or refreshingly spontaneous. He has a tendency to cram as many panels as possible into the pages, especially during the talkative parts. This unfortunately can cramp his artwork, but when Abadzis opens-up the panels, the results can be extremely beautiful.

Laika is a work that wears its heart on its sleeve. It's not difficult to see where the author's sympathy lies. This could easily have wallowed in cheap sentimentality. But the historical realism of the setting, and the compelling characters of the second half of the story manage to keep the story grounded.